Desertion of J. D. Evans

Johnathan D. Evans before the Civil War was residing at Nashville, GA. He was enumerated there as a mechanic in the Census of 1860. A “mechanic” was a craftsman, tradesman or artisan – a skilled worker in manufacturing, production or entrepreneurial trade. Mechanics worked as independent masters or journeymen in manufacturing and trade establishments, railroads, mills, foundries, potteries, bakehouses, tanneries, currieries, coach makers, saddlers, blacksmiths, soap and candle makers, construction, shoe making, boat manufacture, book binding, watchmaking, and so on. The 1860 Census Schedule 2, “Slave Inhabitants” shows Evans was a “slave owner” enumerated with two enslaved people.

At the outbreak of the war, J. D. Evans became Captain of one of the four companies of Confederate soldiers that went forth from Berrien County, GA. His name appears on a March 1862 list of Berrien County men subject to do military duty. He enlisted with other men of Berrien County and was mustered into Company E, 54th Georgia Regiment Volunteer Infantry March 4, 1862. On May 6, 1862, J. D. Evans was elected Captain of Company E. Among other Berrien County men serving in Company E, 54th Georgia Regiment were Jehu and James Patten, George Washington Knight , Matthew Hodge Albritton, James Lee, Jesse Lee, John Lee, George Washington Knight, James Madison Baskin, William Varnell Nix, Stephen Willis Avera, William J. Lamb, Thomas L. Lamb, Samuel Guthrie, William Henry Outlaw, John Webb, Jordan Webb and Benjamin Sirmans, Jeremiah May, Rufus Ray, and Samuel Sanders. Dr. Hamilton M. Talley was Evans’ second in command.

But after a year of service, J. D. Evans deserted his post.

According to the New Georgia Encylopedia,

“Desertion plagued Georgia regiments during the Civil War (1861-65) and, in addition to other factors, debilitated the Confederate war effort. Deserters were not merely cowards or ne’er-do-wells; some were seasoned veterans from battle-hardened regiments…. Whereas the sixty-three plantation-belt counties in the lowlands provided more than 50 percent of the volunteer infantry companies, desertion rates among soldiers hailing from this region were among the lowest in the state…This phenomenon may be partially accounted for by the fact that Confederate social and military authority remained reasonably intact in the lowlands for most of the war, making it perilous for would-be deserters from the area to flee home…The economic structure of the plantation belt and the widespread use of slave labor also allowed lowland Georgians to remain in the Confederate army without worries for the safety of their homes and families. [Furthermore] wealthy plantation owners in the lowlands were able to apply for exemptions. While 3,368 Georgians deserted to Union lines throughout the war, approximately 11,000 affluent Georgia men received exemptions and were able to remain in their communities and maintain social and economic stability.

Berrien County men, like J. D. Evans, did desert, though. Men deserted from Company E (Berrien County), 54th GA Regiment, from the Berrien Minute Men (companies G & K, 29th GA regiment), and from the Berrien Light Infantry (Company I, 50th GA Regiment).

Companies routinely sent patrols back to their home counties to round up deserters and stragglers who had overstayed their leaves. Sergeant William W. Williams was sent in 1864 to hunt skulkers in Lowndes and Berrien County, GA. N. M. McNabb, a soldier of Company D, 12th Georgia Regiment, was pressed into service hunting fugitive deserters in Berrien County in September 1864.

Men who were too old for active service would be formed into details to find deserters and send them back to the Army. Punishment varied widely, but men who deserted, especially multiple offenders, might be executed by firing squad. Nebraska Eadie, who experienced the Civil War as a child in Berrien County, GA, recalled how her uncle Seaborn Lastinger was executed for desertion:

“Uncle Seaborn was shot at sunrise. He was blindfolded standing on his knees by a large pine tree. My father [William Lastinger] took it hard, and recorded it in his record this way: (Shot by those Damned called Details).“

It was not unusual for Confederate soldiers to go absent without having been granted leave. John W. Hagan, sergeant of the Berrien Minute Men, wrote about having to “run the blockade” – to slip past sentries and sneak out of camp for a few hours when he didn’t have a pass. Isaac Gordon Bradwell, a soldier of the 31st Georgia Regiment, wrote from Camp Wilson about his regiment being called to formation in the middle of the night to catch out those men who were absent without leave. The men returned before dawn, but “There was quite a delegation from each company to march up to headquarters that morning to receive, as they thought, a very severe penalty for their misconduct. Our good old colonel stood up before his tent and lectured the men, while others stood armed grinning and laughing at their plight; but to the surprise and joy of the guilty, he dismissed them all without punishment after they had promised him never to run away from camp again.”

The men sometimes gave themselves unofficial leave for more than just a night on the town – French leave, they called it.

Desertion was common from the beginning of the war, but, until early in 1862, it was not always defined as such. When the war unexpectedly lasted past the first summer and fall, … recruits began taking what many called “French leave” by absenting themselves for a few days or longer in order to visit friends and family (the term comes from an eighteenth-century French custom of leaving a reception without saying a formal good bye to the host or hostess). Officers pursued these men with varying degrees of diligence, but because most returned in time for the spring campaigns, few were formally charged with and punished for desertion. – Encyclopedia Virginia

In July 1862 a number of men from the 29th Georgia Regiment were detached to Camp Anderson, near Savannah, for the formation of a new sharpshooter battalion. Desertion became a problem; by the end of the year 29 men would desert from Camp Anderson. At least one deserter killed himself rather than be captured and returned to Camp Anderson. Another, after firing a shot at Major Anderson, was court-martialed and executed by firing squad. Three more deserters were sentenced to death but were released and returned to duty under a general amnesty and pardon issued by Jefferson Davis.

In October 1862 Elbert J. “Yaller” Chapman took “French leave” when the Berrien Minute Men were returning by train from a deployment in Florida:

“Yaller” stepped off the train at the station on the Savannah, Florida, and Western [Atlantic & Gulf] railroad nearest his home — probably Naylor, and went to see his family. He was reported “absent without leave,” and when he returned to his command at Savannah, he was placed in the guard tent and charges were preferred against him. It was from the guard tent that he deserted and went home the second time. After staying home a short while he joined a cavalry command and went west. It is said that he was in several engagements and fought bravely.

Albert Douglas left the Berrien Minute Men “absent without leave” in December 1862 and was marked “deserted.” Actually Douglas enlisted in the 26th Georgia Infantry and went to Virginia, where his unit was engaged in the Battle of Brawners Farm. He subsequently served in a number of units before deserting and surrendering to the U. S. Army. He was inducted into the U. S. Navy, but deserted that position in March 1865.

By the spring of 1863 when the 29th Georgia Regiment was stationed at Camp Young near Savannah, GA, twenty men were reported as deserters. Four of the deserters were from Company K, the Berrien Minute Men, including Albert Douglas, Benjamin S. Garrett, J. P. Ponder and Elbert J. Chapman. Colonel William J. Young offered a reward of $30 for each Confederate deserter apprehended, $600 for the bunch. From the weeks and months the reward was advertised, one can judge these were not men who just sneaked off to Savannah, but were long gone.

Deserter Benjamin S. Garrett was said to have been shot for being a spy. Back in 1856, Benjamin Garrett had been charged in old Lowndes County, GA with drunk and disorderly “public rioting,” along with his brothers Drew and William Garrett, and their cousins John Gaskins, William Gaskins, Gideon Gaskins and Samuel Gaskins; the venue was later changed to the Court of the newly formed Berrien County, but never went to trial.

In April, 1863 deserters from the Confederate works at Causton’s Bluff and Thunderbolt batteries reported that “the daily rations of troops consist only of four ounces bacon and seven of cornmeal.”

When the 29th Georgia Regiment and the Berrien Minute Men, Company K were sent to Mississippi in May of 1863 they encountered deserter Elbert J. Chapman serving in another regiment. The case became one of the most notorious of the war. [Chapman’s] desertion consisted in his leaving [the Berrien Minute Men,] Wilson’s Infantry Regiment, then stationed on the coast of Georgia, and joining a Cavalry Regiment at the front—a “desertion” of a soldier from inactive service in the rear to fighting at the front. Although Chapman was fighting with another company in Mississippi, he was charged with desertion from the 29th Georgia Regiment and court-martialed. Despite appeals by his commanding officers Chapman was executed by firing squad. After the war, his indigent wife was denied a Confederate pension.

While Berrien Minute Men Company G was detached at the Savannah River Batteries, the papers of commanding officer Col. Edward C. Anderson indicate desertions from the Savannah defenses were a common occurrence.

It was in July 1863 that Captain J. D. Evans deserted from Company E, 54th Georgia Infantry Regiment. Given that the 54th Georgia Infantry was engaged in repelling Federal assaults on the defenses of Charleston, his punishment was remarkably light.

Just a few days after J. D. Evans went absent without leave, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, issued a general pardon to deserters.

His proclamation, issued on August 1, 1863, admitted Confederate defeats, the horrific death toll, and the pending invasion of Georgia by overwhelming U.S. forces. Davis claimed the goal of the U.S. government is a slave revolt and the genocide or enslavement of Southern whites. He assuaged the guilt of deserters and asserted that Confederate victory could still be pulled from defeat, if all the Confederate deserters would but return to their camps. Finally, Davis “conjures” the women of Georgia not to shelter deserters from disgrace.

Jefferson Davis’ proclamation of pardon and amnesty for Confederate deserters was published in newspapers all over the South.

TO THE SOLDIERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES.

After more than two years of a warfare scarcely equaled in the number, magnitude and fearful carnage of its battles; a warfare in which your courage and fortitude have illustrated your country and attracted not only gratitude at home but admiration abroad, your enemies continue a struggle in which our final triumph must be inevitable. Unduly elated with their recent successes they imagine that temporary reverses can quell your spirit or shake your determination, and they are now gathering heavy masses for a general invasion, in the vain hope that by a desperate effort success may at length be reached.

You know too well, my countrymen, what they mean by success. Their malignant rage aims at nothing less than the extermination of yourselves, your wives and children. They seek to destroy what they cannot plunder. They propose as the spoils of victory that your homes shall be partitioned among the wretches whose atrocious cruelties have stamped infamy on their Government. The design to incite servile insurrection and light the fires of incendiarism whenever they can reach your homes, and they debauch the inferior race hitherto docile and contented, by promising indulgence of the vilest passions, as the price of treachery. Conscious of their inability to prevail by legitimate warfare, not daring to make peace lest they should be hurled from their seats of power, the men who now rule in Washington refuse even to confer on the subject of putting an end to outrages which disgrace our age, or to listen to a suggestion for conducting the war according to the usages of civilization. Fellow citizens, no alternative is left you but victory, or subjugation, slavery and the utter ruin of yourselves, your families and your country. The victory is within your reach. You need but stretch forth your hands to grasp it. For this and all that is necessary is that those who are called to the field by every motive that can move the human heart, should promptly repair to the post of duty, should stand by their comrades now in front of the foe, and thus so strengthen the armies of the Confederacy as to ensure success. The men now absent from their posts would, if present in the field, suffice to create numerical equality between our force and that of the invaders— and when, with any approach to such equality, have we failed to be victorious? I believe that but few of those absent are actuated by unwillingness to serve their country; but that many have found it difficult to resist the temptation of a visit to their homes and the loved ones from whom they have been so long separated; that others have left for temporary attention to their affairs with the intention of returning and then have shrunk from the consequences of their violation of duty; that others again have left their post from mere restlessness and desire of change, each quieting the upbraidings of his conscience, by persuading himself that his individual services could have no influence on the general result.

These and other causes (although far less disgraceful than the desire to avoid danger, or to escape from the sacrifices required by patriotism, are, nevertheless, grievous faults, and place the cause of our beloved country, and of everything we hold dear, in imminent peril. I repeat that the men who now owe duty to their country, who have been called out and have not yet reported for duty, or who have absented themselves from their posts, are sufficient in number to secure us victory in the struggle now pending.

I call on you, then, my countrymen, to hasten to your camps, in obedience to the dictates of honor and of duty, and summon, those who have absented themselves without leave, or who have remained absent beyond the period allowed by their furloughs, to repair without delay to their respective commands, and I do hereby declare that I grant a general pardon and amnesty to all officers and men within the Confederacy, now absent without leave, who shall, with the least possible delay, return to their proper posts of duty, but no excuse will be received for any deserter beyond twenty days after the first publication of this proclamation in the State in which the absentee may be at the date of the publication. This amnesty and pardon shall extend to all who have been accused, or who have been convicted and are undergoing sentence for absence without leave or desertion, excepting only those who have been twice convicted of desertion.

Finally, I conjure my countrywomen —the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the Confederacy— to use their all-powerful influence in aid of this call, to add one crowning sacrifice to those which their patriotism has so freely and constantly offered on their country’s alter, and to take care that none who owe service in the field shall be sheltered at home from the disgrace of having deserted their duty to their families, to their country, and to their God.

Given under my hand, and the Seal of the Confederate States, at Richmond, this 1st day of August, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three.JEFFERSON DAVIS.

By the President:

J. P. Benjamin, Sec’ry of State.

Johnathan D. Evans did not return to his post, however. In his absence, the 54th Georgia Regiment continued on station. The Georgia Journal and Messenger reported “the 54th Georgia Regiment suffered severely” on the night of August 25 when federal forces assaulted Battery Wagner on Morris Island.

On Oct 23, 1863, Evans’ Colonel wrote to General Samuel Cooper that Evans was a skulker and hiding from duty. (Cooper was the highest ranking officer of the Confederate States Army, outranking Robert E. Lee and all other officers of the Confederacy.)

Hed. Qrs. 54th Ga. Infantry

James Island, S.C.

Oct. 20th, 1863Gen’l S. Cooper

Adj’t Insp’r Gen’l

Richmond,Gen’l

I have the honor to request that you will drop in disgrace from the Army rolls, the name of Captain J. D. Evans of Company “E” 54th Ga. Infantry.

This officer has been absent from his command for a period of sixty days without leave. On the 27th day of July last, the Regiment being ordered to Morris Island, Capt Evans reported sick, and at his own request was sent, by the Surgeon, to the hospital in Charleston. He was subsequently transferred to Columbus, S.C., and thence to Augusta, Ga., since which time he has never reported.

I regret to state that all the circumstances surrounding this case indicate, but too clearly, that he never intends to rejoin his command – at least while it is in active service; (nor from all the reports which reach me) can I be induced to believe that he is sick – on the contrary, I am forced unwillingly to think that he is skulking and hiding from duty. If a more charitable construction could be placed upon his conduct, I should be the last one to suggest so harsh a proceeding in his case.

Where he is – what he is doing – when he intends to return – and where to reach him with an order are questions which no one can answer.

Verbal reports reach me that he is at home with his family – that he is engaged in a Government workshop – but all parties report him well. His influence with his command is lost. For the good of the service, and as a proper example to deter others from adopting a similar course, I earnestly recommend that his name be dropped from the Army Rolls.I have the honor to be, Gen’l,

Very Respectfully,

Yr Ob’t Sv’t

Charlton H. Way

Col. Charlton H. Way letter of October 10, 1863 requesting Capt. J. D. Evans be dropped in disgrace from Army rolls.

Col. Charlton H. Way letter of October 10, 1863 requesting Capt. J. D. Evans be dropped in disgrace from Army rolls.

Evans never did return to his unit. He was dropped from the rolls of Confederate officers for desertion.

The most significant wave of desertion among Georgia soldiers began in late 1863 following the Battle of Chickamauga,…the biggest battle ever fought in Georgia, which took place on September 18-20, 1863. With 34,000 casualties, Chickamauga is generally accepted as the second bloodiest engagement of the war; only the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, with 51,000 casualties, was deadlier.

Lt. H. M. Talley assumed command of Company E, 54th GA Regiment. By the spring of 1864, Company E and the rest of the 54th Georgia Regiment were back at Savannah, GA serving on river defenses under the command of Edward C. Anderson. Anderson’s command also included the Berrien Minute Men, Company G, 29th Georgia Regiment. Col. E. C. Anderson’s frustrations with Confederate desertion included the embarrassment of having his personal boat stolen by three deserters from the Confederate tugboat CSS Resolute on the night of April 15, 1864.

By the summer of 1864, the Confederate States Army was again in pursuit of skulkers. Colonel Elijah C. Morgan of the Georgia Militia, wrote from Valdosta, GA to his superior officer requesting a guard to conduct skulkers back to their units. Col. E. C. Morgan had served as Captain of the Berrien Light Infantry, Company I, 50th GA regiment from the formation of the company in 1862 until April 14, 1863 when he resigned because of tuberculosis; before the war he had been a Berrien County, GA attorney.

Colonel Elijah C. Morgan requests a guard to conduct skulkers from Valdosta, GA back to their Confederate units, August 16, 1864.

Valdosta, Ga Aug 16th 1864

General,

I again urge the necessity of sending Sergt Wm W Williams back to use as a guard in sending forward skulkers who will not do to trust without a guard.

E. C. Morgan

Col. & ADG

6th Dist GM

According to historian Ella Lonn, of the approximately 103,400 enlisted men who deserted the Confederacy by war’s end, 6,797 were from Georgia.

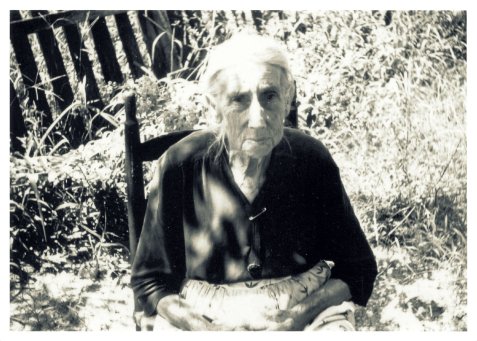

After the war, J. D. Evans became a Baptist preacher. In 1874 he came to Ray’s Mill, GA (now Ray City) where he was instrumental in organizing a missionary Baptist Church.

Related Posts: