This post includes previous material along with additional information about the experience of officers of the Berrien Minute Men held as prisoners of war at Johnson’s Island Military Prison, Lake Erie, Ohio. Events during the 1864-1865 period of their incarceration included induction into the prison, daily life, a tornado, shootings, a plot to liberate the prison, swimming in Sandusky Bay, baseball games, minstrel shows, soldiers dining on rats, cats and dogs, escape attempts, funerals, a Confederate officer giving birth, “swallowing the eagle,” and finally, exchange.

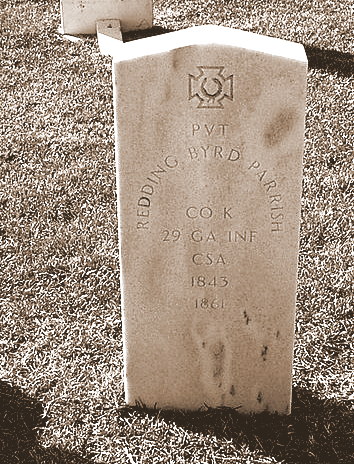

The Berrien Minute Men, a Confederate Infantry unit raised in Berrien County, GA were among those troops engaged in the Battle of Atlanta, July 22, 1864 near Decatur, GA. The Berrien Minute Men had made their campfires and campaigns in Georgia, Florida, South Carolina and Mississippi. Among the officers captured in that battle were Captain Edwin B. Carroll, Captain Jonathan D. Knight, 2nd Lieutenant John L. Hall, 2nd Lieutenant Simeon A. Griffin, 2nd Lieutenant Jonas Tomlinson, and others of the 29th Georgia Regiment (Captain Edwin B. Carroll and the Atlanta Campaign). These officers were transported to the Louisville Military Prison at Louisville, KY then to the U. S. Military Prison at Johnson’s Island. Sergeant John W. Hagan was reported dead, but actually had been captured and sent along with the rest of the captured Confederate enlisted men to Camp Chase, OH.

In all, sixty-two of the Confederate officers captured at Atlanta on July 22nd entered the Johnson’s Island prison population on August 1, 1864. Officers of the 29th Georgia Infantry Regiment already held as prisoners of war at Johnson’s Island included Lieut. Thomas F. Hooper, Berry Infantry.

Captured Confederate officers destined for Johnson’s Island prison were transported to Sandusky, OH and ferried by steam tugs across an arm of Lake Erie three miles to the island. Johnson’s Island is a strip of land one and one-half miles in length, and containing about 275 acres, lying near the mouth of Sandusky bay.

1862 Map of Johnson’s Island Prison, Johnson’s Island, Lake Erie, OH. Image source: https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15138coll3/id/7/

REGULATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES MILITARY PRISON, AT JOHNSON’S ISLAND.

HEADQUARTERS HOFFMAN’S BATTALION, DEPARTMENT OF PRISONERS OF WAR, NEAR SANDUSKY, OHIO, March 1, 1862.

ORDER NO. 1.- It is designed to treat prisoners of war with all the kindness compatible with their condition, and as few orders as possible will be issued respecting them, and their own comfort will be chiefly secured by prompt and implicit obedience.

ORDER No. 2.— The quarters have been erected at great expense by the government for the comfort of prisoners of war; so the utmost caution should be used against fire, as in case of their destruction the prisoners will be subjected to much exposure and suffering for want of comfortable quarters, as others will not be erected and rude shelters only provided.

ORDER No. 3.— All prisoners are required to parade in their rooms and answer to their names half an hour after reveille and at retreat.

ORDER No. 4.— Meals will be taken at breakfast drum, dinner drum, and half an hour before retreat.

ORDER No. 5.— Quarters must be thoroughly policed by 10 o’clock in the morning.

ORDER No. 6.— All prisoners will be required to remain in their own quarters after retreat, except when they have occasion to visit the sinks; lights will be extinguished at taps, and no fires will be allowed after that time.

ORDER No. 7.— Quarrels and disorders of every kind are strictly prohibited.

ORDER No. 8.— Prisoners occupying officers’ quarters in Blocks 1, 2, 3, and 4 will not be permitted to visit the soldiers’ quarters in Blocks 5, 6, 7, and 8, nor go upon the grounds in their vicinity, nor beyond the line of stakes between the officers and soldiers’ quarters, nor will the soldiers be allowed to go upon the ground in the vicinity of the officers’ quarters, or beyond the line of stakes between the officers’ and soldiers’ quarters.

ORDER No. 9.— No prisoners will be allowed to loiter between the buildings or by the north and west fences, and they will be permitted north of the buildings only when passing to and from the sinks; nor will they approach the fences anywhere else nearer than thirty feet, as the line is marked out by the stakes.

ORDER No. 10.- Guards and sentinels will be required to fire upon all who violate the above orders. Prisoners will, therefore, bear them carefully in mind, and be governed by them. To forget under such circumstances is inexcusable, and may prove fatal.

By order of William S. Pierson.

B. W. Wells, Lieutenant and Post Adjutant.

The experience of newly arriving Confederate prisoners was documented in the diary of Lt. William B. Gowen, 30th Alabama Infantry:

“The Officers on Guard who recd us when we landed fairly dazzled ones eyes to look upon with their uniform of blue cloth and white gloves and brass ornaments enough to furnish the old bell maker in Coosa (I forget his name) for the next five years if he only had them. I suppose these fellows have never seen service in the field. If we had them down in the Missippi Swamps a while we could soon take the starch our of them. At Head quarters the roll was called and as each mans name was called, he was required to step up to a table and deliver up his money, if he had any, the amounts were carefully noted, and he was assured that his Confederate money would be returned to him whenever he left the island and that his U.S. money would be held subject to his order, whenever he wished to use it. This ceremony being over with we were marched through a door and found ourselves inside the prison walls. The grounds enclosed by this wall is ten acres square in extent. The wall is about 12 feet in height of plank set up end ways, around the outside of the walls and about three feet from the top is a walk for sentinels on duty. The U.S. Government has gone to considerable expense here in fixing up for the accommodation of Prisoners of War. For this purpose houses have been erected in two rows parallel to each other with 6 houses in each row and a street between about 50 yards in width, also one house in the middle of this street at one end making 13 in all. The buildings are framed, two stories in height with glass windows of good size and sealed inside. They are about 120 ft. in length by 30 ft. in width…These are divided into rooms…each room being furnished with a stove and bunks for the accommodation of five & six men on each bunk a straw matress and one blanket.

Just inside the stockade wall a ditch was constructed around the compound except along the bay side. This ditch facilitated drainage and curtailed the excavation of escape tunnels. Thirty feet inside the stockade wall was the “dead line,” marked out by stakes. “No prisoner could cross this line without being shot; and they were.”

About twenty acres of Johnson’s Island were enclosed in the stockade. “Within this enclosure were fifteen buildings – one hospital, two mess halls, and twelve barracks for the prisoners. The stockade was rectangular, and there was a block-house in each corner and in front of the principal street…The guards… had five block houses with several upper stories pierced for rifles and the ground floors filled with artillery. Moreover, outside the pen there were enclosed earth-works mounting many heavy guns. and the gunboat Michigan with sixteen guns lay within a quarter of a mile.”

Of the twelve barracks within the enclosure, one housed only “those prisoners who had taken the Oath of Allegiance, swearing to support, protect , and defend the Constitution of the United States.” The other 11 barracks were for general housing. Initially, in each of the barracks, Lieutenant Gowan wrote, “there is a cook room furnished with a good cooking stove and utensils to cook in, a table and cupboard & several long shelves, adjoining to this is a dining room furnished with tables and benches. Tin plates, tin cups, table spoons, knives and forks.” But about the time the officers of the Berrien Minute Men arrived, “two large mess halls were built to remove the messes from the individual blocks and to accommodate the increased numbers of prisoners.“

Reproduction of sketch of Confederate officers’ mess at Johnson’s Island Prison in January 1864 by William B. Cox, no date

The stockade also contained a bath house, and on the inland side of the prison, behind the barracks were constructed the latrines. “The latrines were often mentioned in the medical inspection reports due to their offensive and unsanitary nature.” – Latrines of the Johnson’s Island Prison

Outside of the prison wall were forty structures built for the prison staff comprised of barracks, officers’ quarters, band room, lime kiln, express office, post headquarters, stable, storehouses, barn, powder magazine, laundress quarters, and sutler’s store. A redoubt with artillery surrounded the prison facility to

ensure that no riot or insurrection occur.

Company of Johnson’s Island Prison guards at roll call. The barracks building was the same type built for the prisoners. The lean-to buildings on each end were kitchens. In the background is a portion of the stockade wall showing the parapet used by the guards while on duty. http://johnsonsisland.org/history-pows/civil-war-era/

Despite the presence of the prison fortress, Johnson’s Island continued to be a destination of organized boat excursions from nearby towns, which brought picnickers to the island and a brass band for entertainment.

Sixty-two of the Confederates captured at Atlanta on July 22nd, including officers of the Berrien Minute Men entered the Johnson’s Island prison population on August 1, 1864. The indignant prisoners were searched before being taken into the prison.

When the captured officers of the Berrien Minute Men arrived in the pen of Johnson’s Island Prison they found the prisoners there already included Lieut. Thomas F. Hooper of the Berry Infantry, 29th Georgia Infantry Regiment. Hooper had been captured June 19, 1864 at Marietta, GA. Details of Hooper’s capture were documented when a letter addressed to him reached the Berry Infantry days after he became a prisoner of war. The letter, addressed to Lieut. Thomas F. Hooper, 29th Reg Ga Vol, Stevens Brigade, Walkers Division, Dalton, Georgia, was initially marked to be forwarded to the Army of Tennessee Hospital in Griffin, Georgia. But when it was discovered that the addressee had been captured, it was forwarded a second time back to Okolona, MS with ‘for’d 10’ added on the envelope for the forwarding fee. Lieutenant Thomas J. Perry, added a lengthy notation on the back of the envelope.

“Marietta, Ga June 22, 1864 The Lt was captured on the 19th inst out on skirmish. He mistook the enemy for our folks and walked right up to them and did not discover the mistake until it was too late. As soon as they saw him, they motioned him to come to them and professed to be our men. I suppose Capt [John D.] Cameron has written you and sent Andrus on home. The Lt was well when captured. Thos J. Perry.”

Upon his arrival at Johnson’s Island, Hooper had not particularly endeared the Georgia officers to their fellow prisoners, which was perhaps a bit odd as among his own men Hooper was thought a jovial and cool-headed fellow. Capt. W. A. Wash wrote, “Lieut. T. F. Hooper, of Georgia, came into our room by order of Major Scoville, but he did not prove to be an agreeable room mate, and did not stay with us vary long. He had been raised in affluence and indolence, consequently petted and spoiled, and seemed to ignore the fact that there were any duties to perform, or that he was under any obligations to his fellow prisoners. Our room was an institution carried on in a systematic way, every one having his share of duties to discharge. Hooper generally took care to be out of the way when his time came, and, as we were unwilling to wait on him, and neither weak hints nor strong ones had the desired effect, it became disagreeable, and nobody shed tears when he was sent South with a squad of invalids.” – Camp, Field and Prison Life. On the order of

Col. William Hoffman, commissary general of prisoners, Hooper was sent on October 6, 1864 to Fort_Monroe. Five days later he was released in an exchange of prisoners.

Prison Life

Each day for the prisoners began with an early morning formation and roll call, regardless of the weather. An evening version of the same process ended the formal day. Between roll calls and in the evening the prisoners were free to move within the stockade and do whatever they pleased with a few restrictions. -Johnson’s Island Historic Landmark interpretive materials.

All prisoners were required to be in their quarters by sundown. Any prisoner caught outside after dark would be fired upon by the guards.

Arriving in the heat of summer, the men had the unfortunate experience of dealing with the bedbugs that infested the camp.

Any description of Johnson’s Island which contains no mention of bedbugs would be very incomplete. The barracks were cieled, and were several years old. During the cool weather the bugs did not trouble us much, but towards the latter part of May they became terrible. My bunk was papered with Harper’s Weekly, and if at at any time I struck the walls with any object, a red spot would appear as large as the part of the object striking the wall. We left the barracks and slept in the streets…When I get my logarithmic tables and try to calculate coolly and dispassionately the quantity of them, I am disposed to put them at one hundred bushels, but when I think of those terrible night attacks, I can’t see how there could have been less than eighty millions of bushels.

In the summer, upon giving parole that they would not attempt escape, the prisoners were allowed to bath in Sandusky Bay.

“Six hundred of us, unarmed, are splashing, dashing, diving, and ducking, and a few disciples of old Isaac Walton, are fishing, and it is a piscatorial fact, that fish were caught by Confederates, in spite of the antics and noise incidental to the bathing of six hundred prisoners. A line of bayonets bristled at intervals on the beach, and now and then one would be lowered, and a bead drawn on some unwary prisoner, who had swam a little beyond the limits allowed. But bathing, as well as all material things, must have an end, and one by one the prisoners come out of the once limpid bay, arrange their toilet, and prepare for the inner walls.” – Scraps from the Prison Table.

The ice wagon began its summer visits and we gladly welcomed it. We got ice at five cents per pound, and from five to eight pounds daily was enough for a mess of from six to ten men, so the tax was not very heavy – nothing compared with the luxury. The larger messes of from twenty to fifty kept their water in barrels and bought ice accordingly. – Camp, Field and Prison life

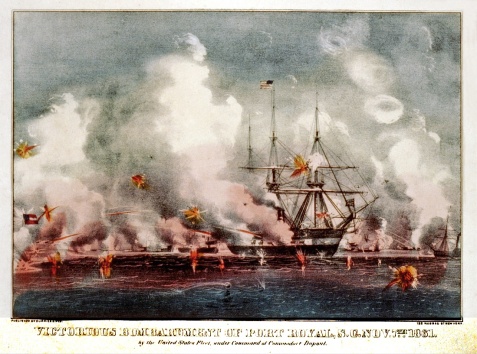

In September of 1864, a Confederate plot to free the prisoners at Johnson’s Island was discovered. The plan was to seize the U.S.S. Michigan (the only armed vessel on Lake Erie) and force the garrison on Johnson’s Island to release the prisoners.

♦

To support the escape plot inside the prison , Major General Isaac Trimble “organized among the prisoners a society known as “The Southern Cross,” having for its emblem a wooden cross twined with the Confederate colors. Its members were bound by iron-clad oaths, administered on the open Bible, to hold themselves in readiness, when the time came, to strike at once a blow for personal liberty and the Southern cause. They were also bound to most solemn secrecy.” -Sketches and Stories of the Lake Erie Islands

♦

Although the attempt was thwarted, it, and previous rumors of attack, led the Union forces to build a lunette and a redoubt on Johnson’s Island and an artillery battery on Cedar Point. – Latrines of the Johnson’s Island Prison

On the night of September 24, 1864 a tornado struck the Johnson’s Island prison, destroying half the buildings, ripping roofs off three of the barracks and one wing of the hospital, and flattening a third of the fence. But in the midst of the gale the Federal guards maintained a picket to prevent any escape. One of the mess halls was wracked and four large trees were blown down in the prison yard. Ten prisoners were injured, only one severely. The stockade fence was repaired by September 29 but it was weeks before the camp was sound again.

Prison Food

“From the prison’s opening until 1864 food was fairly abundant and the prisoners ate about as well as Federal soldiers in the field. [In addition], A sutler store was established within the stockade which sold newspapers, food, clothing, stationary, pens and ink. Almost everything that could be found in a Sandusky store was available in exchange for sutler money. Prices were about twice what was charged across the bay but the prisoners had little choice.” -Johnson’s Island Historic Landmark interpretive materials.

The Sutler’s Store inside Johnson’s Island Prison, drawn by a prisoner in 1864. The prison housed captured Confederate officers, including officers of the Berrien Minute Men.

“Sick” prisoners were allowed to receive packages from home and, according to Capt W. A. Wash, Company I, 60th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, prisoners did receive “nice box[es] of good things to eat” from relatives, including coffee, flour, ham, dried fruit, sweet potatoes, butter – even whiskey and wine, which was prison contraband.

As the war dragged on, outrage grew both sides over the treatment of prisoners of war. Following newspaper reports of the mistreatment of U.S. Army soldiers in Confederate prisons, the U.S. Commissary General of Prisons ordered that Confederate prisoners of war held at Johnson’s Island and other prisons “be strictly limited to the rations of the Confederate army.” Furthermore, the previous practice of allowing prisoners to purchase food from vendors on the prison grounds was disallowed. “On October 10, Hoffman ordered that the sutlers should be limited to the sale of paper, tobacco, stamps, pipes, matches,

combs, soap, tooth brushes, hair brushes, scissors, thread, needles, towels, and pocket mirrors.”

In this period prison meals typically consisted of “pork and baker’s bread” although occasionally the prisoners received codfish and flour. A prisoner at Johnson’s Island wrote,

“Our rations were six ounces of pork, thirteen of loaf bread and a small allowance of beans or hominy – about one-half the rations issued to the Federal troops. The pork rarely had enough grease in it to fry itself, and the bread was often watered to give it the requisite weight. Such rations would keep soul and body together, but when they were not supplemented with something else, life was a slow torture. …the prisoners were not to buy anything [to eat]. The suffering was very great. Men watched rat holes during those long, cold winter nights in hopes of securing a rat for breakfast. Some made it a regular practice to fish in slop barrels for small crumbs of bread, and I have had one man to point out to me the barrel in which he generally found his “bonanza” crumb. If a dog ever came into the pen he was sure to be killed and eaten immediately.” Capt. John Ellis, St. Helena Volunteers, 16th LA Regiment reported cats were also eaten, at least on one occasion.

One group of prisoners collected sap from “sugar trees” growing in the enclosure and attempted to make maple syrup, ending up with maple sugar instead.

For Christmas Day, 1864, Capt Wash, who was on cook detail, recorded in his diary: “We had ham and biscuit for breakfast, pudding for dinner,and will have ‘fish in the dab’ tomorrow morning – I made ‘fish in the dab’ out of out lake shad, and all the scraps of bread, meat, onions, &c., that we had, conglomerated into a batter and fried or baked. I flavored it with sage and pepper, and the boys said they didn’t want anything better. We never wasted an ounce of anything edible.”

Passing the Time

Boredom was a major enemy but the resourceful prisoners managed to combat it in a variety of ways.

Baseball was played in the open area along the southeast stockade wall and the YMCA had provided some 600 books, mostly classical and religious works since books on war and politics were forbidden…On the less cultural side, a poker game could usually be found using worthless Confederate currency which was not even confiscated upon registration. -Johnson’s Island Historic Landmark interpretive materials.

Baseball was a popular prison pastime. Two of the teams were the Confederates and the Southerners. A match game on August 27, 1864 drew considerable interest and significant wagers were placed on the outcome. The Southerners came out on top 19-11 in a nine inning game.

The prison “library” was a popular institution, supplemented by books, magazines, and newspapers contributed by the prisoners. Prisoners could join the library by donating volumes or subscribing for 50 cents per month.

The prisoners provided all kinds of services for themselves; There were cooks, tailors, shoe-makers, chair-makers, washer-men, bankers and bill-brokers, preachers, jewelers, and fiddle-makers. So much was the demand, that a “chair factory” was established in the pen. One enterprising prisoner became a photographer, using a camera he managed to construct from available materials. Another had a washing machine and operated a laundry service. Some prisoners produced and peddled baked goods – apple pies and biscuits.

We had schools of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, Italian, French, German, Theology, Mathematics, English, Instrumental Music, Vocal Music, and a dancing school. The old “stag-dance” began every day except Sunday at 9 a.m., and the shuffling of the feet would be heard all day long till 9 p.m.”

“Tailoring was well done at reasonable rates. Our shoe-makers, strange to say were reliable and charged very moderate prices for their mending. The chair-makers made very neat and comfortable chairs, and bottomed them with leather strings cut out of old shoes and boots. Our washer-man charged only three cents a piece for ordinary garments, and five cents for linen-bosomed shirts, starched and ironed. Our bankers and bill-brokers were always ready to exchange gold and silver for green-backs, and even for Confederate money till Lee’s surrender.”

We had also a “blockade” distillery which made and sold an inferior article of corn whiskey at five dollars, in green-backs, per quart. It was a very easy matter to get the corn meal; but I never could imagine how they could conceal the mash-tubs and the still, so as to escape detection on the part of the Federal officers who inspected the prison very thoroughly two or three times each week.

John Lafayette Girardeau, a slave owner and proponent of white supremacist theology, was famous for his ministry to enslaved people.

We had many preachers, too. Dr. Girardeau, of South Carolina, one of the ablest preachers in the South preached for us nearly every day. Our little Yankee chaplain was so far surpassed by the Rebs that he rarely showed his face.

Major George McKnight, under the nom de plume of “Asa Hartz,” wrote:

There are representatives here of every orthodox branch of Christianity, and religious services are held daily.

The prisoners on Johnson’s Island sent to the American Bible Society $20, as a token of their appreciation for the supply of the Scriptures to the prison.

A theatrical group known as the “Rebel Thespians” wrote and performed original material with great success. Their plays included a five-act melodrama called “Battle of Gettysburg.“

It seems incredible today, but the Confederate prisoners at Johnson’s Island prison were allowed by their Federal captors to create and perform minstrel shows, presumably in blackface makeup. In 1848, Frederick Douglas had called blackface performers, “…the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.”

The “Island Minstrels” in addition to songs, jig dancing and music, performed “the astonishing afterpiece, ‘The Secret, or The Hole in the Fence.‘” The “Rebellonians” gave their debut performance on April 14, 1864; They gave a minstrel performance and concluded with “The Intelligent Contraband,” an original farce written expressly for the “Rebellonians.” Another theatrical group was the Ainsagationians.

These groups somehow even managed to produce printed handbills. According to the Wilmington Semi-Weekly Messenger, “The price of admission to these performances was 25 cents and reserved seats 50 cents. In one of the bills it is announced ‘Children and Niggers Half Price.’ The proceeds of the shows were for the benefit of the Confederate sick in the prison hospital.“

We have a first-class theater in full blast, a minstrel band, and a debating society. The outdoor exercises consist of leap-frog, bull-pen, town-ball, base-ball, foot-ball, snow-ball, bat-ball, and ball. The indoor games comprise chess, backgammon, draughts, and every game of cards known to Hoyle, or to his illustrious predecessor, “the gentleman in black.” There were a number of ball clubs which competed in the various sports. Other games played in the prison yard included “knucks” and marbles. Other prisoners took up gardening in the prison yard.

There was a Masonic Prison Association, Capt. Joseph J. Davis, President, which sought to provide fresh fruit and other food items to sick prisoners in the prison hospital. The hospital was staffed by one surgeon, one hospital steward, three cooks, and seven prisoner nurses. Medical and surgical treatment was principally provided by Confederate surgeons.

The cemetery at Johnson’s Island was at the extreme northern tip of the island, about a half mile from the prison.

Digging graves in the island’s soft loam soil was not difficult. However, between 4 feet and 5 feet down was solid bedrock. It was officially reported that the graves were “dug as deep as the stone will admit; not as deep as desirable under the circumstances, but sufficient for all sanitary reasons.” The graves were marked with wooden headboards. – Federal Stewardship of Confederate Dead

Major McKnight described funerals at the prison, poignantly referring to the dead as “exchanged” (released from prison):

Well! it is a simple ceremony. God help us! The “exchanged” is placed on a small wagon drawn by one horse, his friends form a line in the rear, and the procession moves; passing through the gate, it winds slowly round the prison walls to a little grove north of the inclosure; “exchanged” is taken out of the wagon and lowered into the earth – a prayer, and exhortation, a spade, a head-board, a mound of fresh sod, and the friends return to prison again, and that’s all of it. Our friend is “exchanged,” a grave attests the fact to mortal eyes, and one of God’s angels has recorded the “exchange” in the book above. Time and the elements will soon smooth down the little hillock which marks his lonely bed, but invisible friends will hover round it till the dawn of the great day, when all the armies shall be marshaled into line again, when the wars of time shall cease, and the great eternity of peace shall commence.

Confederate burial ground, Johnson’s Island. Here in a spot as lonely as was ever selected for the burial of the dead, under branches low bending, amid shadows and silence, appeared long rows of sodden mounds, marked only by wooden headboards bearing each the name and age of deceased, together with the number of the command to which he had belonged.

Two prisoners of Johnson’s Island were released by order of President Abraham Lincoln, issued on December 10, 1864. The Tennessee men were released after their wives appealed to the President, one pleading her husband’s case on the basis that he was a religious man.

When the President ordered the release of the prisoners, he said to this lady: “You say your husband is a religious man; tell him when you meet him that I say I am not much of a judge of religion, but that, in my opinion, the religion that sets men to rebel and fight against their Government because, as they think, that Government does not sufficiently help some men to eat their bread in the sweat of other men’s faces, is not the sort of religion upon which people can get to heaven.”

On November 9, 1864, Sandusky bay froze over. In early December the prison got a blanket of snow. Monday, the 12th of December was the coldest day of the year, and perhaps one of the strangest at Johnson’s Island Prison. That night a group of prisoners rushed the fence, perhaps thinking they could make their escape over the ice. The guards managed to push them back; the next day four corpses were placed in the prison dead-house. Ohio newspapers reported Lt. John B. Bowles, son of the President of the Louisville Bank, was among the dead.

Birth at Johnson’s Island Prison

Earlier in the day on December 12, 1864, a Confederate officer gave birth to a “bouncing boy.” The woman and child were paroled from the prison. Northern newspapers ran the story.

Woman posing as Confederate officer gives birth at Johnson’s Island Prison – The Tiffin, OH Weekly Tribune, December 15, 1864

Strange Birth. – We are credibly informed that one day last week, one of the rebel officers in the”Bull Pen,” as our soldiers call it: otherwise, in one of the barracks in the enclosure on Johnson’s Island, in which the rebel prisoners are kept, gave birth to a “bouncing boy.” This is the first instance of the father giving birth to a child we have heard of; nor have we read of it “in the books.” The officer, however, was undoubtedly a woman and, we may say it is the first case of a woman in the rebel service we have beard of, though they are noted for goading their own men into the army, and for using every artifice, even to their own dishonor, to befog, and befuddle some of our men. It was in all probability profit, not patriotism, or love, as is the case with the girls that go into the United States service disguised as men, which led this accidental mother into the rebel ranks. The ladies of chivalry are prodigal of their tongues, and chary and choice of their persons. Sandusky Register 13th.

The question has been asked whether the young rebel just ushered into the world on Johnson’s Island, draws rations in the regular way: Another question is, is he doomed to involuntary servitude, his parent being a “Confederate”? prisoner? Does he follow his mother’s condition or his father’s? The Cleveland Herald thinks his father would be hard to find but his mother knows he’s out! -Register, 14th

Does the little stranger promptly answer at roll call, and make his reports regularly? With the true spirit of the Southerner, does he cry for vengeance or over “spilled milk?”

Berrien Minute Men Second Lieutenants James A. Knight and Levi J. Knight, Jr. , and Capt. John W. Turner, Berry Infantry, arrived at the prison on December 20, 1864; From the 30th GA Regiment, which had been consolidated with the 29th GA Regiment, the arrivals that day were Lt. Daniel A. Moore, Lt. William L. Moore, Capt. Hudson Whittaker, and Capt. Felix L. Walthall. All had been captured at the Battle of Franklin, TN on December 16, 1864.

Col. William D. Mitchell, 29th Georgia Regiment. Image Source: Tim Burgess https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/26944690/william-dickey-mitchell

December 22, 1864 was snowy, windy and bitter cold at Johnson’s Island. New arrivals at the prison on that day included Col. William D. Mitchell, 29th, GA Regiment; Lacy E. Lastinger; 1st Lieutenant Thomas W. Ballard. Captain Robert Thomas Johnson, Company I, 29th Regiment, arrived at the prison. Lastinger, 1st Lieutenant from Berrien Minute Men, Company K, 29th GA Regiment and Ballard, Company C, 29th GA had been captured December 16, 1864 at Nashville, TN. Other arriving prisoners from the 29th GA Regiment included 2nd Lieutenant Walter L. Joiner, Company F.

Edwin B. Carroll and the other prisoners passed Christmas and New Years Day on Johnson’s Island with little to mark the occasion.

Lieutenant Colonel John W. Inzer, 58th Alabama Regiment, wrote

Saturday, January 21, 1865

Received letter from Sister Lou, written Oct. 30th. Mailed Ft. Monroe January 16th. Not quite so cold. Hill Yankee published an order this morning ordering the small rooms, the best quarters, or enough of them to be evacuated by the present occupants, to accommodate the oath takers and men who do not wish to go South on exchange. It is hard to be thus imposed on by traitors and scoundrels. A man must be very corrupt, indeed, to be a member of this villainous crowd. I fear we will have to move. I never expect to give my consent to swallow the oath. – “Tales from a Civil War Prison“

By February 1865, Confederate POWs at Johnson’s Island were being exchanged for the release of Federal POW’s imprisoned in the South.

On March 29, Major Lemuel D. Hatch, 8th Alabama Cavalry, wrote from Johnson’s Island,

For several months we suffered here very much for something to eat, but all restrictions have now been taken off the sutler and we are living well… The extreme cold of last winter and the changeableness of the climate has been a severe shock to many of our men. I notice a great deal of sickness especially among the Prisoners captured at Nashville. Nearly all of them have suffered with rheumatism or pneumonia since their arrival.

The end of the war came with Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865 and, for Georgians, the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate Army to General William T. Sherman at the Bennett Place, April 26, 1865.

The surrender of Genl. Joe Johnston near Greensboro N.C., April 26th 1865

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pga.09915

To leave Johnson’s Island a prisoner was required to take an Oath of Allegiance to the United States, as by accepting Confederate citizenship they had renounced their citizenship in the United States. The Confederate prisoners called taking the oath “swallowing the eagle,” and men who swore allegiance to the United States were called “razorbacks,” because, like a straight-edged razor whose blade can be flipped every which way, they were considered spineless by their fellow inmates.

The prisoner had to first apply to take the Oath. He was then segregated from the prison population and assigned to a separate prison block. This was done for the safety of those taking the Oath as they were now repudiating their loyalty to the Confederacy. Until 1865, only a small number of prisoners took the Oath because of their fierce devotion and loyalty to the cause for which they were fighting. However, in the Spring of 1865, many prisoners did take the Oath, feeling the cause for which they fought so hard was dead. The following letter written by prisoner Tom Wallace shows that “swallowing the eagle” (taking the oath) was not done without a great deal of soul searching. http://johnsonsisland.org/history-pows/civil-war-era/letters-to-and-from-confederate-prisoners/

Thomas Wallace, 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Kentucky Regiment wrote from Johnson’s Island in 1865 about taking the Oath of Allegiance:

My dear mother,

Perhaps you may be surprised when I tell you that I have made application for the “amnesty oath”. I think that most all of my comrades have or will do as I have. I don’t think that I have done wrong, I had no idea of taking the oath until I heard of the surrender of Johnston and then I thought it worse than foolish to wait any longer. The cause that I have espoused for four years and have been as true to, in thought and action, as man could be is now undoubtedly dead; consequently I think the best thing I can do is to become a quiet citizen of the United States. I will probably be released from prison sometime this month.

Wallace took the Oath on June 11, 1865. Captain Felix L. Walthall, 30th GA Regiment, “swallowed the eagle” on June 17, 1865

Oath of Allegiance of Captain Felix L. Walthall, 30th GA Regiment, Wilson’s Brigade, Walker’s Division. June 17, 1865.

I do solemnly swear that I will support, protect, and defend the Constitution and Government of the United States against all enemies, whether domestic or foreign; that I will bear true faith, allegiance and loyalty to the same, any ordinance, resolution, or laws of any State, Convention, or Legislature notwithstanding; and further, that I will faithfully perform all the duties which may be required of me by the laws of the United States; and I take this oath freely and voluntarily, without any mental reservation of evasion whatever.

From early on at Johnston’s Island, Confederates who swore the Oath of Allegiance were immediately moved into a separate barracks to protect them from attacks from zealous rebels. Prisoners who accepted the Oath received special treatment. Capt. William L. Peel wrote:

“They draw more commissaries, however, than we do. Their ration being 20 oz. bakers bread, 16 oz. meat and small quantities of beans or hominy, salt, vinegar, etc. per day.”

Archaeological evidence associated with the barracks where the Oath takers were housed documents such special treatment. “The vast quantities of wine, whiskey, champagne, and beer bottles attest to the “special” treatment that these prisoners were receiving.” – Latrines of the Johnson’s Island Prison

Edwin B. Carroll swore the Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America on June 14, 1865 at Depot Prisoners of War, Sandusky, OH. He was then described as 24 years old, dark complexion, dark hair, hazel eyes, 5’11”

After spending almost a year in the Johnson’s Island prison, Edwin B. Carroll was released in June 1865.

When the War ended, and he returned home, he could find no employment but teaching, in which he has been engaged almost every year since… In October, 1865, he was married to Mrs. Julia E. Hayes, of Thomasville, Georgia.

Related Posts:

- Edwin B. Carroll, Captain of the Berrien Minute Men

- Captain Edwin B. Carroll and the Atlanta Campaign

- Owen Clinton Pope, Reconstruction Teaching and Preaching

- Levi J. Knight, Jr on List of Incompetent Confederate Officers

- Campfires of the Berrien Minute Men

- The Poetry of Mary Elizabeth Carroll

- Grand Rally at Milltown