Louisa Bird Peurifoy (1816-1878) was the wife of Reverend Tillman Dixon Peurifoy (1809-1872), a circuit-riding Methodist preacher who served on the Troupville Circuit in Lowndes County, GA in 1840. Old Lowndes County then also encompassed much of present day Berrien, Cook, Tift, Lanier and Echols counties and Troupville was the county seat for the pioneer settlers of Ray City, GA. In 1838, the Peurifoys lived in the Florida Territory, about 20 miles from Tallahassee. On the night of Saturday, March 31, 1838, while Reverend Peurifoy was away at a Methodist conference meeting, his family and African Americans he enslaved were massacred by Indians. The two PePrevious Nexturifoy children and three enslaved people were killed in the attack. Mrs. Peurifoy was horribly wounded.

Louisa Ann Bird Peurifoy was born September 10, 1816 in Edgefield County, SC. She was a daughter of Lucinda Brooks and Captain Daniel Bird. Her father, a native of Virginia, was a wealthy cotton planter and breeder of fine race horses. He owned hundreds of acres of land and twenty enslaved people. “In 1817 he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives where he served in the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth General Assemblies (1818-1822). In 1822 he was elected Clerk of Court for the Edgefield District in which office he served from 1822 until 1830.“

It appears in Louisa’s early childhood the family lived on one of her father’s plantations. When she was about nine, her father moved the family into Halcyon Grove, a magnificent mansion he had built near the Edgefield court house.

“The house was three stories, including the full attic. Two huge chimneys were at each end, providing fire places for the front rooms on the first and second floors. Two smaller chimneys were behind for the back rooms. The front porch was a narrow, two-story portico which was common in the early antebellum period. (This would later be changed to the porch we see today which extends across the entire front of the house.) Other architectural features included elaborately-carved mantelpieces, wainscoting, and an arch dividing the downstairs hallway. Additionally there were fanlights over the main hall doors upstairs and down, and a partially hidden staircase at the back hall leading to the second floor. The hardware for all of the doors was brass and of the best quality, for the hinges and locks have lasted for nearly two centuries. By any standards, this was, as a later commentator described it, ‘a handsome establishment, and a large and comfortable one.’”

The Story of Halcyon Grove

Louisa’s mother, Lucinda Brooks, died in 1826, and her father subsequently married Mrs. Behethland Brooks Simkins, sister of his deceased wife. The step-mother, Mrs. Simkins, was the widow of Jesse Simkins who had left her possessed of lands, money and enslaved people. Mrs. Simkins had four children of her own; Elizabeth Simkins, Emmala Simkins, Smith Simkins and Lawrence Simkins who became Louisa’s step-siblings.

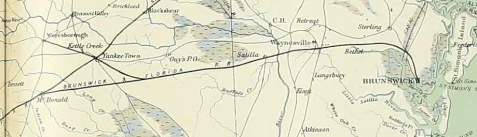

In 1830, Captain Bird’s household was enumerated in Edgefield County, SC with his wife and their nine children, and 14 enslaved people. Around that time, Captain Bird purchased a tract of land in Jefferson County in the Florida Territory, just south of the line of Lowndes County, GA. In 1832, Captain Bird moved his family, enslaved people and household goods from South Carolina to settle in Jefferson County, Florida Territory. The Bird’s most likely route through Wiregrass Georgia would have been via the Coffee Road which was opened up in 1827, the same year Jefferson County was created, and which ran from Jacksonville, GA to Tallahassee, FL. Arriving in Florida, the Birds first alighted at Waukeenah, about 11 miles south of Monticello, FL. Waukeenah was a resting point for travelers on the Old St. Augustine road (also known as the Bellamy Road), which ran from St. Augustine to Tallahassee to Pensacola, Florida.

Within a very short while, Captain Bird relocated to “Bunker Hill”, about 10 miles northwest of Monticello, FL where he established a large plantation. Bunker Hill was a rise on the mail route from Thomasville, GA to Monticello, FL; A post office with mail delivery every two weeks had been established there in 1829. Later Captain Bird bought a second plantation named “Nacoosa” south of Monticello, which had been the home of Abram Bellamy (Jefferson County Library Digital History Project). By 1860, Bunker Hill Plantation and Nacoosa Plantation together comprised 1600 acres, where Bird worked 44 enslaved people.

On June 13, 1833, Louisa Ann Bird married Tillman Dixon Peurifoy in Jefferson County, FL. The bride was 17 years old, the groom 25. Purifoy was a circuit riding Methodist minister who had been sent to Jefferson County to support the Methodist Episcopal Church’s mission in the Florida Territory, and a contemporary of Wiregrass circuit riders George W. Davis, Robert H. Howren, George Bishop, Capel Raiford, Robert Stripling, and John Slade. T.D. Peurifoy was a son of William Peurifoy born January 21, 1809 in Putnam County, GA. He had been baptized into the Methodist faith at the age of 15. The Southern Christian Advocate said, “He commenced in the old Methodist way, leading the class, holding prayer-meetings in the neighbor hood, etc., and soon became very popular among the people, and useful in the church.” At 19 he was admitted as a minister in the Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. His father died the following year, and by age 21, he was appointed by the Georgia Conference to a station at Waynesboro, GA, riding on horseback to preach in communities in the area.

After marriage, Louisa and Tillman D. Peurifoy did not immediately settle in the Florida Territory. In October, 1833, Reverend Peurifoy was in Sparta, GA. Great camp meetings attended by thousands of Methodists were held at Shoulderbone Creek near Sparta. In those days, Methodists held camp meetings all over Georgia. In Lowndes County an annual Methodist revival was held at the old Lowndes Camp Ground, later called the Mount Zion Camp Ground.

In Putnam County, the Methodist gathered at the Rock Spring Camp Meeting. On October 4, 1833, while attending the camp meeting at Rock Spring, Reverend Peurifoy’s brother was robbed of a fine pocket watch, of the lever type; The lever escarpment mechanism, popularized in the 1820s, made a significant advancement in the accuracy of pocket watches.

For the year 1834 the church assigned Reverend Peurifoy to the Cedar Creek station near Milledgeville, Baldwin County, GA.

“It is located in perhaps the most beautiful valley in Georgia. Cedar Creek, a considerable stream, clear as

crystal, meanders through the valley, and along its banks are lands unsurpassed in fertility. The mountains are round about. Attracted by the beauty and fertility of the valley, many citizens of culture and wealth removed to it, and it became and has continued to this day a most delightful station.” (- A History of Methodism in Georgia & Florida) The Cedar Creek Circuit covered some 1,400 square miles and ran through Jasper, Jones and Baldwin County, and a part of Putnam County, which was the county of Rev. Peurifoy’s birth. “Clinton, the county-site of Jones, was an appointment in the old Cedar Creek Circuit. It was a place of considerable importance, being in the midst of a fine cotton-producing country. In it there was much wealth and style, and alas ! infidelity and dissipation.“

At the January 1835 meeting of the Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, young Reverend Peurifoy was serving in the St. Mary’s District. The conference was poorly attended “owing to the inclement weather.” It was reported that 27 ministers had not returned to appointments because of retirement or other reasons. Seventeen new ministers were appointed on trial. Peurifoy was one the few ministers in the conference without an appointment.

By 1838 Louisa had given her husband two children, Elizabeth Peurifoy and Lovic Pierce Peurifoy. Reverend Peurifoy was assigned to the Alachua Mission in the Florida Territory. The mission station was about two miles from the plantation home of Louisa’s father, Captain Daniel Bird and about twelve miles from Suwannee Springs, FL. The Peurifoys worked, and worked their enslaved people to carve a homestead for the Peurifoys out of the wilderness.

It was a perilous time to be on the southern frontier. There was a rising storm of conflict between the growing European-American population and Native Americans who violently resisted subjugation and removal to lands west of the Mississippi. Indians and whites spilled blood across Wiregrass Georgia and Florida. The Indian Wars had been underway since 1836. In Berrien County, GA skirmishes had been fought along the Alapaha River and a battle at Brushy Creek. In 1838, Captain Levi J. Knight had a militia company in the field in south Georgia.

But in the Florida Territory it was said the real fighting was a hundred miles distant from the area where the Peurifoys were homesteading, and part of Rev. Peurifoy’s Methodist mission was ministry to the Indians. He continued in his work and travels in the Alachua Mission, undoubtedly thinking his family was safe enough on their north Florida homestead.

That sense of security was shattered when the Peurifoy home place was destroyed. Louisa, her children and the Peurifoy’s enslaved people were at the homestead on the evening of March 31, 1838 when the Indians attacked. Her husband was away at a meeting of the church conference perhaps a two- or three-days ride distant. Within days, vivid accounts of the massacre were widely circulated in newspapers across the Wiregrass.

– On Saturday evening last, about dark, a party of Indians, supposed to number 30 or 40, attacked the dwelling of Mr. Purifoy, residing in the vicinity of the previous depredations, murdered two children and three negroes, plundered and set fire to the buildings, and made their escape – the children were burned in the dwelling. Mrs. Purifoy, although severely wounded, miraculously made her escape from the savages. When the attack was made there were none but females about the premises, a fact supposed to have been known to the Indians. Mrs. P. was lying in bed with her two children, heard a noise in her room and on looking up found it filled with Indians, who commenced discharging their rifles, several of them aimed at herself and children. The children it is supposed were killed at once. Mrs. P. received a ball in her shoulder, which passed out at her breast. The savages next commenced hacking and stabbing her with their knives, and inflicted a number of severe wounds on her head and several parts of her body. Their attention was a moment directed from her to a noise made by the servants in an adjoining room, when Mrs. P. taking advantage of this circumstance escaped to the yard, where she was again shot down, but succeeded in gaining the woods, intending to reach her father’s residence, Capt. Daniel Bird, about two miles distant. Faint from the loss of blood and the severity of wounds, she was unable to proceed more than half a mile, where she was found next morning. Mrs. P. received, we understand, ten distinct wounds, several very severe, but her physician entertains strong hopes of her recovery. – To heighten the catastrophe, Mr. Purifoy, whose children and slaves were slain, was absent from home, fulfilling his ministerial duties.

As soon as the attack was discovered, the troops at Camp Carter, under Capt. Shehee, were sent for, but the Indians had dispersed in three parties and fled. Maj. Taylor with Capt. Newsam’s company joined Capt. S. on Monday morning, and have followed the several trails, but with what success we have not understood.

The house attacked is several miles within the frontier settlements – the houses of most of which are picketed in. We trust the occurrence will awaken the United States authorities to do something more for the protection of our frontier. – Tallahassee Floridian

The wounded Louisa was carried on a makeshift stretcher to her father’s house. Most thought her wounds so grievous she could not live. When a letter carrying word of the attack reached Reverend Peurifoy at the conference he rushed home, but could not have arrived sooner than four or five days after the attack. Louisa, gravely wounded, was still clinging to life. In anguish, Rev. Peurifoy wrote a letter to his friend William Capers, a fellow Methodist minister and editor of the Southern Christian Advocate. Capers published the letter and news of the Peurifory Massacre was printed in newspapers around the world.

In time, Louisa got better, although some said she never fully recovered. Her little children, her home, her furnishings, all her possessions were lost. Of their Florida homestead, only the 11 surviving African-Americans enslaved by the Peurifoys remained.

Within months of the attack, Tillman Dixon Peurifoy submitted a claim to the federal government seeking compensation for “slaves killed by Indians.” Under an act of Congress, citizens were entitled to receive payment for their loss of “slave property.” But the House Committee on Indian Depredation Claims found adversely for Peurifoy’s claim, as the Government was “not liable for the loss of private property taken by the public enemy in time of war.“

January 22, 1839

Read, and laid upon the table.Mr. Giddings from the Committee of Claims, submitted the following REPORT:

The Committee of Claims, to whom was committed the petition of T. D. Peurify, report:

That the memorialist, in his petition, states that, on the first day of April, A. D. 1838, during the temporary absence of the petitioner, the Indians burnt his dwelling-house, situated in Jefferson county, in the Territory of Florida, destroyed his personal property, (including his household furniture,) and murdered three of his slaves, for which he asks indemnity.

The committee view the claim, as stated by the petitioner, to be one of those cases of loss by Indian depredations which have so often come before the committee and the House of Representatives, and on which indemnity has been uniformly refused. The Committee refer to the report of the Committee of Claims upon the memorial of the Legislature of the State of Alabama, made at the last session of the present Congress, (vide Reps. of Com. vol. 4, No. 932,) where the principles of that report, and recommend to the House the adoption of the following resolution:

Resolved, That the petition is not entitles to relief.

Thomas Allen, print.

After the massacre, Tillman Dixon Peurifoy took his wife and surviving enslaved people out of the Florida Territory and returned to Georgia. In the census of 1840 Tillman and Louisa, now with a young son, and 11 enslaved people were enumerated at Grooverville, GA. Grooverville was at the crossing of the Thomasville & Madison Road, and Sharpe’s Store Road, perhaps 15 miles east northeast of Bunker Hill. Lebanon Church, the Methodist house of worship at Grooverville, had been established about 1832.

Tillman D. Peurifoy was then appointed to the Troupville station in the Florida District, Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Troupville, GA about 30 miles east of Grooverville, was then the seat of government of Lowndes County, GA. Troupville was the center of commerce and social activity for the region. The town was situated immediately in the fork made by the confluence of the Withlacoochee and Little rivers. It was the site of the Lowndes County courthouse and jail, hotels, Methodist and Baptist churches, stores, shops, doctors and lawyers. Among residents of the town circa 1840 were William McAuley, Hiram Hall, John Studstill, William Lastinger, Joseph S. Burnett, William McDonald, William D. Branch, Jonathan Knight, William Smith, and James O. Goldwire. “Of the merchants who did business there in the old days, were Moses and Aaron Smith, E. B. Stafford, Uriah Kemp, and Alfred Newburn,” according to an 1899 Sketch of Old Lowndes County. The Knight family, who were the original pioneer settlers of present day Ray City, GA, were among the prominent citizens of Lowndes County who frequented the town.

In January, 1841 the Peurifoys likely suffered yet another setback when floodwaters of the Harrison Freshet inundated Troupville. The low-lying town was completely flooded. When the annual Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church convened in Macon, GA that month, Robert Howren was appointed to Troupville. No station appointment was reported for Tillman D. Peurifoy.

Between tragic losses in 1838 and possibly further difficulties in the flood of 1841, the Peurifoys were struggling financially. To get by Rev. Peurifoy was forced to borrow money from wealthier men in the area. He borrowed from John Bellamy, a planter in the Florida Territory; Thomas County, GA plantation owner Mitchell Brady Jones; Postmaster Daniel McCranie; Ebenezer J. Perkins; Thomas Robinson; and others. Given Wiregrass Georgia’s burgeoning slave economy, many of these loans were secured or settled through the mortgaging, selling or trading of enslaved peoples. Peurifoy himself was enumerated in the 1840 Census as the owner of 14 enslaved people. In the Grooverville district of Thomas County where the Peurifoys lived, more than half of the residents were enumerated as “owners” of enslaved African Americans. In Thomas County, the population in 1840 was 3,836 whites and 2,930 enslaved African-Americans; by 1860 the enslaved population of Thomas County outnumbered the white population 6,244 to 4,488.

In January, 1842, Tillman D. Peurifoy borrowed $3,500 dollars from John Bellamy (1777-1845), putting up seven enslaved people as collateral for the loan. Bellamy was one of the wealthiest planters and most prominent political figures in the Florida Territory. His 3000 acre plantation was in Jefferson County along the Aucilla River east of Monticello. In 1826, Bellamy had been the government contractor for the construction of the Bellamy Road which was built with the labor of enslaved African Americans, and followed the path of the Old St. Augustine Road from St. Augustine to Tallahassee. Like the Coffee Road in south Georgia, the Bellamy Road did much to open the north Florida Territory for settlement.

In January 1843, Reverend Peurifoy was appointed to the Methodist station for Cuthbert and Fort Gaines, GA on the Chattahoochee River. Fort Gaines was the site of the Fort Gaines Female Institute and the Independent College for Young Men, boarding schools (not colleges as that word is used today) founded by Sereno Taylor, a prominent Baptist minister and owner of four enslaved people.

The financial woes of the Peurifoys continued in 1843. Legal documents show authorities in Leon County, Florida ordered the sale of his goods to settle debts, including the sale of people he enslaved.

Reverend Peurifoy had apparently been unable to repay the loan from John Bellamy and on January 19, 1843 Bellamy petitioned Judge Samuel James Douglas of the Superior Court of the Middle District of Florida for satisfaction. An abstract of the petition states the following without noting the outcome.

John Bellamy seeks to foreclose on a mortgage for seven slaves, signed by Tilman D. Peurifoy on 8 January 1842 as security for a promissory note of $3,500. The plaintiff maintains that Peurifoy has “wholly neglected and refused and still doth refuse to pay the same or any part thereof to your petitioner.” Bellamy asks that the slaves be sold, and if the proceeds of the sale are not sufficient to pay the debt, that other property of Peurifoy be subject to sale.

UNC Race & Slavery Project

In Thomas County, GA the Peurifoys were forced to give up their household possessions to be auctioned off to satisfy debts owed to Thomas Robinson and Daniel McCranie.

In order to satisfy a debt owed to the firm of Jones & Baily the Thomas County Sheriff seized “slave property” of the Peurifoys in the person of the enslaved man Shedrach. The 30-year-old African-American man had likely been born into slavery in the United States to live in bondage his entire life. (The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves went into effect January 1, 1808, although some smuggling of slaves continued in southern states all the way up to the Civil War. But the population of enslaved people continued to grow in the U.S. and the domestic slave trade flourished.)

Peurifoy also owed money to Ebenezer J. Perkins and others. Perkins was known as a money lender… and known for assiduously collecting the debts owed to him. Perkins had been indicted in May 1831 “for the offense of malicious mischief in breaking open the door of the boarding house of Isaac P. Brooks to the great annoyance of Mr. Brooks and his boarders.” At one time Perkins had partnered with Hamilton Sharpe, the well-know Methodist, merchant, and postmaster in Lowndes County, GA. In April 1843, Ebenezer J. Perkins, Mitchell B. Jones, and the firm of Jones & Bailey demanded the auction of a Thomasville city lot owned by Peurifoy in order to collect money Peurifoy owed them. A year later, Perkins was stabbed to death after attending the hanging of Samuel Mattox at Troupville, GA.

Thomas Sheriff’s Sales

Milledgeville Southern Recorder, April 04, 1843

Will be sold before the Court house door in the town of Thomasville, Thomas county, on the first Tuesday in April next, within the usual hours of sale, the following property, to wit…

one lot in the town of Thomasville, known as No 3, in square letter E, containing one half acre, with all the improvements thereon – levied on as the property of Tilman D. Purifoy to satisfy the following fi fas, two in favor of Mitchell B. Jones, one in favor of Ebenezer J. Perkins, and one in favor of Jones & Bailey, all vs said Tilman D. Purifoy

Even Reverend Peurifoy’s fellow Methodist ministers were among the debt collectors. Rev. Anderson Peeler, a circuit rider in the Florida District, acquired a lien against Peurify which had originally been filed by Mitchell B. Jones in the Thomas County, GA Inferior Court. At Rev. Peeler’s request the Thomas County Sheriff seized “property” owned Peurifoy to be auctioned off to settle the debt owed to him. The “property” was an enslaved African-American woman named Polly, who had likely suffered all the 50 years of her life in bondage. The “slave auction” was held on the steps of the Thomas County Courthouse, at Thomasville, GA.

In 1843, the Georgia Conference of the Methodist church assigned Rev. T.D. Peurifoy to the station at Cuthbert and Ft. Gaines, GA.

By the 1840s, the ownership of enslaved people by ordained ministers generated substantial controversy within the Methodist Episcopal Church, as the national organization had long opposed slavery. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, had been appalled by slavery. Bishop James O. Andrew, of Georgia, was criticized by the 1844 General Convention for his ownership of enslaved people and suspended from office until such time as he should end his “connection with slavery.” Southern members disputed the Convention’s authority to discipline the bishop or to require slave-owning clergy to emancipate the people whom they considered as property. The differences over enslavement of human beings that would divide the nation during the mid-19th century were also dividing the Methodist Episcopal Church. The 1844 dispute led Methodists in the South to break off and form a separate denomination, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MEC,S), that accommodated slave ownership for its leaders as well as its members. By 1850 the U.S. Census of “Slave Inhabitants” of Georgia shows that Bishop James O. Andrew was the “slave owner” of 24 enslaved people.

Rev. T.D. Peurifoy was given the station at Lumpkin, GA for 1844. In January 1845, he was preaching in the Augusta District and assigned to the Waynesboro station. His circuit then included New Hope Church at Hephzibah, GA, one of the unheated, hewn log churches of the old pioneer days. “It was the rule or custom of this church to construe attendance upon its ‘love feasts’ for three consecutive occasions as prima facie evidence of a desire to enter its communion.” By about 1847, the membership had dwindle such that it ceased to serve as a house of worship.

In 1845, The Peurifoys were still deeply in debt. Louisa Peurifoy’s grandfather Zachariah S. Brooks gave her three enslaved people; a young African-American woman, her daughter, and her ten-year-old brother. These three enslaved people were deeded to Edmund Penn to hold in trust for Louisa, likely a move to protect this “slave property” from seizure by her husband’s creditors and to assure that they remained Louisa’s “property.” But in 1854, the Peurifoys would petition the State of South Carolina to break the trust and allow them to sell the enslaved young man, now 19 years-of-age.

Petition to the Chancellors of the State of South Carolina

UNC Digital Library on American Slavery

Abstract:

Louisa and T. D. Peurifoy seek to sell a slave, whom she holds in trust. In 1845, Louisa’s grandfather, Zachariah S. Brooks, deeded to “Edmund Penn three negro slaves to wit Emily & her child Sarah & her brother Allen to be had & held in trust for” Louisa. Allen “is now about nineteen years old & is stout and able-bodied– but the said Allen is at the same time refractory, insubordinate & unruly.” The Peurifoys “have endeavored to control & govern him but in vain– that the said Allen will not submit to their authority or discipline & the result has been that the said slave contributes but little to their comfort or profit.” The Peurifoys pray that the court authorize Penn “to make sale” of Allen “and to invest the proceeds of such sale in the purchase of one or more negro slaves of more docile & submissive character.”

The Peurifoys remained in the area of Augusta for the next couple of years. In 1846 they were living at The Rocks, about five miles from the city. They continued to sell off or rent out their enslaved people.

In 1846 Reverend T. D. Purifoy’s station was the Columbia Circuit. In 1847, he was sent to the Louisville Station.

Meanwhile, back in Florida, debt collectors were still after Peurifoy for the money he had borrowed from John Bellamy in 1842. Bellamy had died in 1845, but the Administrator of the Estate sought satisfaction in the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, FL. Whether Peurifoy responded to the court order to return to Florida or ever made good on the debt is not known.

Some time before 1850, the Peurifoys left Georgia and returned to Louisa’s roots in Edgefield County, SC, about 25 miles north of Augusta, GA. The 1850 enumeration of the Peurifoys in the Edgefield District lists Reverend and Mrs. Peurifoy, and their children, Daniel B. Peurifoy, Mary I. Peurifoy, Martha C. Peurifoy, and Eliza Peurifoy. Also in the Peurifoy household was a carpenter named John Dean.

Schedule 2 “Slave Inhabitants” in the 1850 Census shows that Rev. Peurifoy was the “Slave owner” of 14 enslaved people.

The 1850s saw a great revival among the Methodists in Edgefield, SC and Reverend T.D. Peurifoy played a prominent role in organizing the camp meetings that drove the revival spirit. In 1851, Peurifoy served on the Building Committee for Bethlehem Camp Ground

A multitude of religious revivals within the Methodist faith in Edgefield were reported throughout the decade in the pages of the Advertiser. The majority of these occurred at spring and summer camp meetings at both Mount Vernon Camp Ground and Bethlehem Camp Ground, both prominent Methodist camp meeting locations in the county… All of these drew large, passionate crowds and produced large numbers of conversion experiences and increased church membership… These revivals were a very public outpouring of religious fervor, and were instrumental in placing the evangelical faith at the forefront of community life in Edgefield.

– Fighting For Revival

In South Carolina, Peurifoy’s preaching took him to New Chapel Church in Newberry County, about 40 miles north of Edgefield. An intimate friend…says in the Christian Neighbor, “I knew brother Peurifoy in the strength of his manhood, his sermons were pungent and powerful. He possessed the power of sharpening the arrows of truth, and hurling them with tremendous force into the ranks of the enemies of the cross. I first heard him in Newberry at New Chapel. Crowds flocked to hear him, and hung on his lips. Many were awakened and converted.“

In 1855, T.D. Peurifoy was in the Shelbyville District, SC. But in 1856, he was “located” at his own request.

By 1860, it seems the Peurifoys had recovered from their previous debt. In the Census of 1860, Reverend Peurifoy’s real estate and personal property were valued at $22,875, which probably placed him in the top 10 percent of the wealthiest people in the Saluda Regiment, Edgefield District, South Carolina. Tillman Peurifoy’s occupation was given as farming. Much of the Peurifoys wealth was represented in the 15 people they enslaved, who ranged from an 80-year-old woman to a four-year-old girl. The Peurifoy’s son, Daniel, worked as the Overseer.

It appears Louisa & Tillman Peurifoy remained in Edgefield County throughout the Civil War. Their son, Daniel Bird Peurifoy, served in the Confederate Army.

About 1862, Rev. Peurifoy suffered a paralytic stroke, “his strength failed, but he continued to preach as often as he could.” He was a representative of the Butler Circuit at the July 30, 1868 Cokesbury District Meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South at Edgefield Courthouse. Peurifoy was appointed to the Committee on Family and Religion. His old friend William T. Capers was the delegate from the Cokesbury station.

Children of Louisa Bird and Tillman Dixon Peurifoy (birth dates from census records):

- Elizabeth Peurifoy (unknown–1838)

- Lovic Pierce Peurifoy (unknown–1838)

- Daniel Byrd Peurifoy (1839–1909), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- Mary Jane Peurifoy (1843–1910), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- Martha C. Peurifoy (1846–1900), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- Eliza A. Peurifoy (1849–1872), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- William Bascom Peurifoy (1854–1927), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- Julia Butler Peurifoy (1855–1931), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

- Sallie Peurifoy (1858–1931), burial at Butler UMC Cemetery

The Census of 1870 shows that the Peurifoys remained in Edgefield County in the Saluda Division during Reconstruction. Their post office was at Oakland. The value of Peurifoy’s total estate had been reduced to $400 dollars.

In April, 1872 Reverend Peurifoy had a second stroke, “his work was done. He lingered for several weeks – never murmured, but was patient and resigned to the will of God from the beginning. And when he could no longer tell us, as he frequently had, of the peace and joye he realized through faith in Christ, (having lost the power of speech,) he would make signs with the hand he could move.” Rev. Peurifoy died June 4, 1872. He was buried in the cemetery at Butler Church, Saluda, SC.

The following tribute of respect was passed at Butler Church Conference, South Carolina.

Southern Christian Advocate, October 23, 1872

Whereas, It has pleased Almighty God in his wise providence, to take out of this world the soul of our beloved brother, Rev. T. D. Peurifoy; therefore,

Resolved, That in the death of the Rev. T. D. Peurifoy, the Church has lost one of her most faithful ministers, the community one of its most honorable citizens.

2. That although we mourn the sad loss we have sustained in the death of brother Peurifoy, we bow in humble submission to the will of Him whose ways are true and righteous altogether.

3. That this Church Conference tender our hearty sympathies to the wife and children of the deceased, in this their sad bereavement, and commend them to the protection of Him, who has promised that His grace shall be sufficient at all times, for those who love, serve and obey Him.

Rev. G. W. McCreighton, Ch’n.

W. S. Crouch, Sec.

Louisa Peurifoy died July 4, 1878. She was buried next to her husband in the Butler Church cemetery.

Related Posts:

- Riders of the Troupville Circuit: Tillman Dixon Peurifoy

- Early Days on the Georgia Frontier

- George W. Davis ~ Methodist Circuit Rider

- The Harrison Freshet

- In Salem Church

- Reverend Robert H. Howren ~ Methodist Circuit Rider

- The Old Log Church

- Fifty Years of Methodist Ministers ~ Ray City, GA

- A Brief History of the Ray City Methodist Church