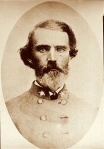

Edwin B. Carroll, Captain of the Berrien Minute Men, Company G, 29th Georgia Regiment.

Edwin B. Carroll

In the Civil War, E. B. Carroll served in the leadership of the Berrien Minute Men, one of four companies of Confederate infantry sent forth from Berrien County, GA.

After serving on Confederate coastal artillery at Battery Lawton on the Savannah River the Berrien Minute Men, Company G, 29th Georgia Regiment, finally ended their long detached duty in Savannah and went to rejoin the 29th Georgia Regiment at Dalton, GA. The 29th Regiment was to be part of the Confederate forces arrayed northwest of Atlanta in the futile attempt to block Sherman’s advance on the city. By this time the ranks of the 29th Georgia regiment had been decimated by casualties and disease. The 29th Regiment “in September, 1863, had been consolidated with the 30th Regiment. The unit participated in the difficult campaigns of the Army of Tennessee at Chickamauga, endured Hood’s winter operations in Tennessee, and fought at Bentonville. In December, 1863, the combined 29th/30th totaled only 341 men and 195 arms,” according to battle unit details provided by the National Park Service.

The Berrien Minute Men departed Savannah April 26, 1864 by train at the depot of the Central of Georgia Rail Road. (The building now serves as the Savannah Visitors Center). Col. Anderson saw the men off

Tuesday, 26th April… at 4 1/2 repaired to the CRR Depot to see the Lawton Batty Co’s go off – They parted with me with every demonstration of regard – Many of the men coming up & shaking hands with me.”

Four days later, the 54th GA Regiment was dispatched to Dalton GA to join the Confederate defensive positions against Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Anderson noted in his Journal:

Saturday, April 30, 1864

The 54th Regt, Col Way left this morning en route for Dalton. I understand they left many stragglers behind.

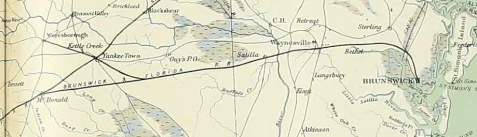

Apparently by June of 1864 Captain Carroll was present for at least part of the Battle of Marietta. By this time it seems an exaggeration to call the 29th Georgia a regiment. The unit was assigned to General Claudius Wilson’s, C.H. Stevens’, and Henry Rootes Jackson‘s Brigade in the Confederate Army of Tennessee, led at that time by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Henry R. Jackson in 1860 had attended the arrival of the first train to reach Valdosta, GA.

Sherman first found Johnston’s army entrenched in the Marietta area on June 9, 1864. The Confederate’s had established defensive lines along Brushy, Pine, and Lost Mountains. Sherman extended his forces beyond the Confederate lines, causing a partial Rebel withdrawal to another line of positions.

Harpers Weekly illustration – Sherman’s view of Kennesaw Mountain from Pine Mountain, from a sketch drawn about June 15, 1864. In the distance is a view of Marietta. Between the two mountains the smoke ascends from three Federal encampments, belonging to the armies of the Cumberland, the Ohio, and the Tennessee. The Confederates under General Johnston hold a strong position on Kennesaw Mountain.

By June 15 1864, Sherman’s army was occupying the heights on Pine Mountain, Lost Mountain and Brushy Mountain. On that day H.L.G. Whitaker, Thomas County Volunteers, Company I, 29th GA Regiment wrote home telling of the death of his friend Chesley A. Payne. Payne was a private in Company B, Ochlockonee Light Infantry, 29th GA Regiment.

“Dear beloved ones, I will say to you that my dear friend C. A. P. [Chesley A. Payne] was cild [killed] on the 15 of June. Robert Reid was standing rite by him syd of a tree. Dear friends it is a mistake about his giting cild [killed] chargin of a battry, nothing more than a line of battle. So I cant tell you eny thing more about him.”

On the Federal line Pvt Charles T. Develling, 17th Ohio Regiment recorded the day’s of skirmishing.

June 17th, we moved to front line. Companies D. and H. skirmished all night. We built breastworks, and rebels attacked us but were repulsed. June 18th, Companies C. and F. charged rebel pickets capturing 4 and driving the rest into their breastworks, fighting nearly 2 hours without support, when our brigade came up and fought till dark. Company C had 1 killed and 2 wounded. J

On Saturday, June 18, 1864 the Confederate newspaper dispatches reported:

Three Miles West of Marietta, June 18 – The enemy has moved a large number of his forces on our left. Cannonading and musketry are constant, amounting almost to an engagement. The rains continue to render the roads unfit for military operations. The indications are that our left and centre will be attacked. The army is in splendid spirits and ready for the attack. A deserter came in this morning drunk. But few casualties yesterday on our side…

June 19. Rain has been falling heavily and incessantly the greater part of last night and all this morning. – Columbus Times, 6/20/1864

Pvt Charles T. Develling, 17th Ohio Regiment continued in his journal:

June 19th, daylight revealed the fact that the rebels had retreated [Johnston had withdrawn the Confederate forces to an arc-shaped position centered on Kennesaw Mountain.] We pursued them, day spent in skirmishing; very heavy artillery firing from our batteries. Night found us in front of Kenesaw Mountain fronting east, skirmishing with the rebels, and fortifying with dispatch. We advanced to within about 700 yards of the rebel’s works, and kept their artillery silent with musketry. Threw up a temporary fort at night for our artillery.

June 20th, our skirmish line, is within 15 or 20 yards of the rebels. We have three lines of works. Heavy skirmishing all along the line. Our artillery gave the rebels a terrific shelling this evening.

June 21st, the rebels got their artillery in position or the mountain and began shelling our camps, immediately our batteries opened and there was one of the grandest artillery duels of the war. Heavy skirmishing in our front just before night; our men held their ground.

“Kennesaw’s Bombardment, 64”, sketch of Union artillery in the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, by Alfred Waud,

On the Confederate side of the line, on June 21st and 22nd John W. Hagan, of the Berrien Minute Men, wrote battlefield letters to his wife, Amanda Roberts Hagan, in which he refers to Captain Edwin B. Carroll.

Letters of John W. Hagan:

In Line of Battle near Marietta, Ga

June 21st 1864

My Dear Wife I will drop you a few lines which leaves Ezekiel & myself in good health. James was wounded & sent to Hospital yesterday. He wounded in the left thygh. It was a spent ball & made only a flesh wound after the ball was cut out and he was all right. He stood it allright. I think he will get a furlough & he will also write to you when he gets to Hospital. We had a fight day before yesterday & yesterday on the 19th we had a close time & lost a grate many in killed & wounded & missing. The 29th [GA Regiment] charged the Yankees & drove them back near 1/2 mile or further. I cannot give a list of the killed & wounded in the fight. In Capt Carrells [Edwin B. Carroll] there was only one killed dead & several wounded. Lt J. M. Roberts [Jasper M. Roberts] was killed dead in the charge & Sergt. J. L. Roberts [James W. Roberts] of our company was killed dead & Corpl Lindsey wounded. Capt Knight is in command of the Regt. Capt. Knight & Capt Carrell is all there is in the Regt. The companies is all in commanded by Lieuts & Sergts. I have been in command of our company 3 days. Lieut Tomlinson [Jonas Tomlinson] stays along but pretends to be sick so he can not go in a fight but so long as I keep the right side up Co. “K” will be all right. The most of the boys have lost confidence in Lt Tomlinson. As a genearl thing our Regt have behaved well. If the casualties of the Regt is got up before I send this off I will give you the number but I will not have time to give the names. You must not be uneasey about James for he is all right now. Ezekiel stands up well & have killed one Yankee. I do not know as I have killed a Yankee but I have been shooting among them. You must not be uneasy about me and Ezekiel for we have our chances to take the same as others & if we fall remember we fell in a noble cause & be content that we was so lotted to die, but we hope to come out all right. Ezekiel hasent bin hit atal & I have bin hit twice but it was with spent balls & did not hurt me much. I was sory to hear of Thomas Cliffords getting killed for he was a gallant soldier & a noble man. I havent time to write much but if we can find out how many we lost in the 19th & 20th I will give a statement below. Ezekiel has just received yours of the 15th & this must do for and answer as we havent time to write now & we do not know when we will have a quiet time. You speak of rain. I never was in so much rain. it rains incisently. Our clothing & blankets havent been dry in Sevearl days & the roads is all most so we can not travel atal. I will closw & write again when I can get a chance. You must write often. Ezekiel sends his love to you all. Tel Mr. and Mrs. Giddins that Isbin is all right. Nothing more. I am as ever yours

affectsionatly

J. W. H.

P.S. as to Co. G being naked that is not so. All have got there cloths that would carry them. Some threw away there cloths but all have cloths & shoes yet. E.W. & Is doesn’t threw thayen away & have plenty. P.S. since writing the above another man of Co. G. is wounded.

♦

In Line of Battle near Marietta, Ga

June 22, 1864

My Dear Wife, As I have and opportertunity of writing I will write you a few lines this morning. I wrote to you yeserday but I was in a grate hurry & could not give you the casualities of the Regt. & I can not yet give you the names but I will give you the number killed wounded & missing in the Regt. up to yesterday 6 oclock P.M. we had 83 men killed wounded & missing & only 7 but what was killed or wounded. This is only the causalties since the 14th of this month & what it was in May I do not know. I do not beleave any of Co. “G” have writen to Jaspers [Jasper M. Roberts] mother about his death & if you get this before She hears the correct reports you can tell her he was in the fight of the 19th & was killed dead in a charge he was gallantly leading & chering his men on to battle and was successfull in driving back the Yankees. He was taken off the battle field & was burried as well as the nature of the case would permit. Our Regt suffered a grate deal on the 19th & some on the 20th. I was in the hotest of this fight & it seemes that thousand of balls whisled near my head, but I was protected. Heavy fighting is now & have been going on for some time on our right & left & I beleave the bloodiest battle of the war will come off in a short time & I feel confident that when the yankees pick in to us right we will give them a whiping, but Gen Johnston dos not intend to make the attack on them.

Amanda, I want you to go & see John C. Clements & find out when he is coming to camps & I want you to sen me some butter by John in a bucket or gord or jar. You can not send much for John can not get much from the R. Road to our camps. You must not send me the book I wrote for some time ago. I can not take care of anything in camps now. You must be shure to go & see cosin Sarah Roberts & tel her about Jasper. I would write to her but I have a bad chance to write on my knee. This leaves Ezekiel & myself in good health & hope you and family are the same

I am as ever your aff husband

J. W. Hagan

P. S. if any of the old citizens from that settlement comes out here, you can send me some butter and a bottle or two of syrup by them. Parson Homer came out some time ago & brought Co. G a nice lot of provissions &c.

In the evening of the 22nd, on the Federal side of the line, Pvt Charles T. Develling, 17th Ohio Regiment wrote in his journal.

June 22nd, the rebels gave us a severe shelling this afternoon, from five different points. Our artillery replied promptly and with effect. Shortly after dark we moved to the right and into front line, already fortified, in an open field, in the hottest hole we have yet found, as regards both the sun and fire from the rebels.

General Sherman’s Campaign – The Rebel Charge on the Right, Near Marietta, GA, June 22, 1864. Harpers Weekly illustration of the Battle of Kolb’s Farm, four miles west of Marietta, June 22, 1864. On the Federal line, General Schofield held the extreme right; on his left, General Hooker commanded the Marietta Road; General Howard held the center; and Palmer and McPherson extended the Federal line to Brush Mountain, on the railroad. Nearly all day the rebels engaged Howard, to divert attention from the right, where they were massing troops on the Marietta Road against Hooker. A furious attack was made by the Rebels at this point at five P.M.

Southern newspapers claimed the fighting on June 27th as a victory for the South, reporting that Cleburne’s Division and Cheatham’s division had killed 750 federal troops along the front and inflicted another 750 casualties in the Federal lines. General Hardee’s Corps and General Loring’s corps were credited with inflicting nearly 8,000 casualties. “Five hundred ambulances were counted from the summit of Kennesaw Mountain to Big Shanty.” – Daily Chattanooga Rebel, June 30,1864

On June 28th, John W. Hagan wrote Amanda of more casualties in the Berrien Minute Men

I haven’t any news to write you that would interest you much. There hasent been much fighting neather on the right or left today & we beleave the Yankees are trying to flank us again. We have had a hard time & have lost about 100 killed wounded & missing. We had our Lieut of Co. “B” killed yesterday. Liut. Ballard of Co. “C” wounded and R. Bradford [Richard Bradford] of Co. “G” wounded & one leg cut off. I hope times will change soon &c. I hear today James had got a furlough for 30 days & was gone home. I hope it is true & I want you to send me a box of something the first chance you get. Send me some butter & a bottle of syrup & some bisket if you see a chance to get them direct through. Also send us some apples if you can get any in the settlement. John Clemants or James Matthis might bring it. Express it to Atlanta & then ship it to Marietta in care of the Thomas County Releaf Society. I think old Lowndes & Berrien is not very patriotic or they would dispach some man from that section with something for the soldiers who are fighting for them daley. Many things might be sent us & some one sent with it. Thomas County has its society out here & do a great deal for the sick & wounded & many boxes are shiped through them to fighting troops…

From the Front

Further Particulars of Monday’s Fight

Marietta, [Wednesday], June 29th [1864] –Unusual quiet prevails along the lines to-day, the enemy being permitted to bury his fast putrifying dead…

Following the retreat from Kennesaw Mountain, the Berrien Minute Men were in the line of battle at Marietta, GA on July 4, 1864. After dark, the Confederate forces withdrew to take up a new defensive line on the the Chattahoochee River. In a letter to his wife, John William Hagan wrote about the Confederate retreat to the Chattahoochee and his confidence in the defensive works of General Joseph E. Johnston’s River Line and the Shoupades. These earthwork fortifications along the north bank of the Chattahoochee, some of the most elaborate field fortifications of the Civil War, were constructed under the direction of Artillery Commander, Brig. General Francis A. Shoup.

In the Battle of Atlanta, Edwin B. Carroll was captured July 22, 1864 near Decatur, GA along with Captain John D. Knight, 2nd Lieutenant John L. Hall, Jonas Tomlinson and others of the 29th Georgia Regiment.

In the Berrien Minute Men Company G, Sgt William Anderson, 2nd Lieutenant Simeon A. Griffin, 2nd Lieutenant John L. Hall, Captain Jonathan D. Knight were captured. James A. Crawford was mortally wounded. Levi J. Knight, Jr. was wounded through the right lung but recovered. Robert H. Goodman was killed. In the Berrien Minute Men Company K, Wyley F. Carroll, James M. Davis, James D. Pounds, William S. Sirmans, and Jonas Tomlinson were captured. John W. Hagan was reported dead, but was captured and sent to Camp Chase.

In the Berrien Light Infantry, Company E, 54th Georgia James M. Baskin was wounded in the hip; he spent the rest of the war as a POW in a U.S. Army hospital.

In a letter written from camp near Atlanta, H.L.G. Whitaker reported Robert Reid, Ocklocknee Light Infantry, Company B, 29th GA Regiment was among those killed on July 22. In the Ocklocknee Light Infantry David W. Alderman, John L. Jordan, Thomas J. McKinnon, P. T. Moore were wounded; Mathew P. Braswell and Joseph Newman were captured.

Among the Thomasville Guards, Company F, 29th GA Infantry the wounded were Stephen T. Carroll, Marshall S. Cummings, Thomas S. Dekle, Walter L. Joiner. Private Green W. Stansell and Sgt D. W. McIntosh were killed; Ordinance Sgt R. A. Hayes was mortally wounded. John R. Collins was missing in action,

In the Alapaha Guards, Company H, 29th GA Infantry, Joseph Jerger was wounded and captured. In the Georgia Foresters, Company A, 29th GA, H. W. Brown and 1st Corporal Furnifull George were captured. Richard F. Wesberry shot in the leg, was sent to Ocmulgee hospital where his leg was amputated. In the Thomas County Volunteers, Company I, M. Collins, Alexander Peacock were wounded; Captain Robert Thomas Johnson and Ransom C. Wheeler wounded and captured. Thomas Mitchell Willbanks was wounded in the leg, necessitating amputation.

For Captain E. B. Carroll the fighting was over. A prisoner of war, he was put on the long journey to a northern prison camp.

On September 17, 1864 Captain E. B. Carroll was being held prisoner near Jonesboro, GA. A few days later on August 31 – September 1, 1864 remnants of the 29th Georgia Regiment were engaged in the Battle of Jonesboro. Apparently Captain Carroll’s kid brother, David Thompson Carroll, had joined the Berrien Minute Men by this time. Seventeen-year-old David T. Carroll had left school in the spring of 1862 and traveled to St. Marks, FL to enlist with the 5th Florida Infantry, but after 2 1/2 months of service had been discharged with a hernia and “epileptic convulsions.” Although the official service records of the Confederate States Army do not document that he re-enlisted, both Edwin B. Carroll and William H. Lastinger later reported that David T. Carroll was a soldier of the Berrien Minute Men and that he was among the men killed in the Battle of Jonesboro. Hundreds of Confederate dead, including men from the Berrien Minute Men and probably David T. Carroll, were buried in unmarked graves at Jonesboro in the yard of the train depot which is now Patrick Cleburne Cemetery.

In 1890 Edwin B. Carroll would return to the Battlefield at Jonesboro where he found rusting weapons still lying about the abandoned earthworks.

After his capture, Edwin B. Carroll and other Confederate prisoners were transported to the Louisville Military Prison at Louisville, KY then to the U. S. Military Prison at Johnson’s Island.

Prisoners were transported to Sandusky, OH and were conveyed by steam tugs across an arm of Lake Erie three miles to Johnson’s Island. Johnson’s Island contains about one hundred acres, twenty of which were enclosed in a stockade…Within this enclosure were fifteen buildings – one hospital, two mess halls, and twelve barracks for the prisoners. The stockade was rectangular, and there was a block-house in each corner and in front of the principal street…The guards… had five block houses with several upper stories pierced for rifles and the ground floors filled with artillery. Moreover, outside the pen there were enclosed earth-works mounting many heavy guns. and the gunboat Michigan with sixteen guns lay within a quarter of a mile.”

Despite the presence of the prison fortress, Johnson’s Island continued to be the destination of organized boat excursions from nearby towns, which brought picnickers to the island and a brass band for entertainment.

Sixty-two of the Confederates captured at Atlanta on July 22nd entered the Johnson’s Island prison population on August 1, 1864. The indignant prisoners were searched before being taken into the prison.

Sketch of U. S. Military Prison at Johnson’s Island, Lake Erie.

Arriving in the heat of summer, the men had the unfortunate experience of dealing with the bedbugs that infested the camp.

Any description of Johnson’s Island which contains no mention of bedbugs would be very incomplete. The barracks were cieled, and were several years old. During the cool weather the bugs did not trouble us much, but towards the latter part of May they became terrible. My bunk was papered with Harper’s Weekly, and if at at any time I struck the walls with any object, a red spot would appear as large as the part of the object striking the wall. We left the barracks and slept in the streets…When I get my logarithmic tables and try to calculate coolly and dispassionately the quantity of them, I am disposed to put them at one hundred bushels, but when I think of those terrible night attacks, I can’t see how there could have been less than eighty millions of bushels.

Men of the 29th Georgia Infantry Regiment already at Johnson’s Island included Lieut. Thomas F. Hooper, Berry Infantry.

Hooper had been captured June 19, 1864 at Marietta, GA. Details of Hooper’s capture were documented when a letter addressed to him reached the Berry Infantry days after he became a prisoner of war. The letter, addressed to Lieut Thomas F. Hooper, 29th Reg Ga Vol, Stevens Brigade, Walkers Division, Dalton, Georgia, was initially marked to be forwarded to the Army of Tennessee Hospital in Griffin, Georgia. But when it was discovered that the addressee had been captured, it was forwarded a second time back to Okolona, MS with ‘for’d 10’ added on the envelope for the forwarding fee. Lieutenant Thomas J. Perry, added a lengthy notation on the back of the envelope.

“Marietta, Ga June 22, 1864 The Lt was captured on the 19th inst out on skirmish. He mistook the enemy for our folks and walked right up to them and did not discover the mistake until it was too late. As soon as they saw him, they motioned him to come to them and professed to be our men. I suppose Capt [John D.] Cameron has written you and sent Andrus on home. The Lt was well when captured. Thos J. Perry.”

Thomas F. Hooper, Berry Infantry, 29th Georgia Infantry Regiment

Thomas J. Perry writes about capture of Thomas F. Hooper near Marietta, GA on June 19, 1964

On the night of September 24, 1864 a tornado struck the Johnson’s Island prison, destroying half the buildings, ripping roofs off three of the barracks and one wing of the hospital, and flattening a third of the fence. But in the midst of the gale the Federal guards maintained a picket to prevent any escape. One of the mess halls was wracked and four large trees were blown down in the prison yard. Ten prisoners were injured, only one severely. The stockade fence was repaired by September 29; it was weeks before the camp was sound again.

As the war dragged on, outrage grew both sides over the treatment of prisoners of war. Following newspaper reports of the mistreatment of U.S. Army soldiers in Confederate prisons, the U.S. Commissary General of Prisons ordered that Confederate prisoners of war held at Johnson’s Island and other prisons “be strictly limited to the rations of the Confederate army.” Furthermore, the previous practice of allowing prisoners to purchase food from vendors on the prison grounds was disallowed. “On October 10, Hoffman ordered that the sutlers should be limited to the sale of paper, tobacco, stamps, pipes, matches,

combs, soap, tooth brushes, hair brushes, scissors, thread, needles, towels, and pocket mirrors.”

A prisoner at Johnson’s Island wrote,

“Our rations were six ounces of pork, thirteen of loaf bread and a small allowance of beans or hominy – about one-half the rations issued to the Federal troops. The pork rarely had enough grease in it to fry itself, and the bread was often watered to give it the requisite weight. Such rations would keep soul and body together, but when they were not supplemented with something else, life was a slow torture. …the prisoners were not to buy anything [to eat]. The suffering was very great. Men watched rat holes during those long, cold winter nights in hopes of securing a rat for breakfast. Some made it a regular practice to fish in slop barrels for small crumbs of bread, and I have had one man to point out to me the barrel in which he generally found his “bonanza” crumb. If a dog ever came into the pen he was sure to be killed and eaten immediately.”

The prisoners provided all kinds of services for themselves; There were cooks, tailors, shoe-makers, chair-makers, washer-men, bankers and bill-brokers, preachers, jewelers, and fiddle-makers.

We had schools of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, Italian, French, German, Theology, Mathematics, English, Instrumental Music, Vocal Music, and a dancing school. The old “stag-dance” began every day except Sunday at 9 a.m., and the shuffling of the feet would be heard all day long till 9 p.m.”

“Tailoring was well done at reasonable rates. Our shoe-makers, strange to say were reliable and charged very moderate prices for their mending. The chair-makers made very neat and comfortable chairs, and bottomed them with leather strings cut out of old shoes and boots. Our washer-man charged only three cents a piece for ordinary garments, and five cents for linen-bosomed shirts, starched and ironed. Our bankers and bill-brokers were always ready to exchange gold and silver for green-backs, and even for Confederate money till Lee’s surrender.”

We had also a “blockade” distillery which made and sold an inferior article of corn whiskey at five dollars, in green-backs, per quart. It was a very easy matter to get the corn meal; but I never could imagine how they could conceal the mash-tubs and the still, so as to escape detection on the part of the Federal officers who inspected the prison very thoroughly two or three times each week.

John Lafayette Girardeau, a slave owner and proponent of white supremacist theology, was famous for his ministry to enslaved people.

We had many preachers, too. Dr. Girardeau, of South Carolina, one of the ablest preachers in the South preached for us nearly every day. Our little Yankee chaplain was so far surpassed by the Rebs that he rarely showed his face.

Major George McKnight, under the nom de plume of “Asa Hartz,” wrote:

There are representatives here of every orthodox branch of Christianity, and religious services are held daily.

The prisoners on Johnson’s Island sent to the American Bible Society $20, as a token of their appreciation for the supply of the Scriptures to the prison.

We have a first-class theater in full blast, a minstrel band, and a debating society. The outdoor exercises consist of leap-frog, bull-pen, town-ball, base-ball, foot-ball, snow-ball, bat-ball, and ball. The indoor games comprise chess, backgammon, draughts, and every game of cards known to Hoyle, or to his illustrious predecessor, “the gentleman in black.”

There was a Masonic Prison Association, Capt. Joseph J. Davis, President, which sought to provide fresh fruit and other food items to sick prisoners in the prison hospital. The hospital was staffed by one surgeon, one hospital steward, three cooks, and seven prisoner nurses. Medical and surgical treatment was principally provided by Confederate surgeons.

On November 9, 1864, Sandusky bay froze over. In early December the prison got a blanket of snow. Monday, the 12th of December was the coldest day of the year, and perhaps one of the strangest at Johnson’s Island Prison. That day one of the POW officers gave birth to a “bouncing boy”; the woman and child were paroled from the prison. That night a group of prisoners rushed the fence, perhaps thinking they could make their escape over the ice. The guards managed to push them back; the next day four corpses were placed in the prison dead-house. Ohio newspapers reported Lt. John B. Bowles, son of the President of the Louisville Bank, was among the dead.

The cemetery at Johnson’s Island was at the extreme northern tip of the island, about a half mile from the prison.

Digging graves in the island’s soft loam soil was not difficult. However, between 4 feet and 5 feet down was solid bedrock. It was officially reported that the graves were “dug as deep as the stone will admit; not as deep as desirable under the circumstances, but sufficient for all sanitary reasons.” The graves were marked with wooden headboards. – Federal Stewardship of Confederate Dead

Major McKnight described funerals at the prison:

Well! it is a simple ceremony. God help us! The “exchanged” is placed on a small wagon drawn by one horse, his friends form a line in the rear, and the procession moves; passing through the gate, it winds slowly round the prison walls to a little grove north of the inclosure; “exchanged” is taken out of the wagon and lowered into the earth – a prayer, and exhortation, a spade, a head-board, a mound of fresh sod, and the friends return to prison again, and that’s all of it. Our friend is “exchanged,” a grave attests the fact to mortal eyes, and one of God’s angels has recorded the “exchange in the book above. Time and the elements will soon smooth down the little hillock which marks his lonely bed, but invisible friends will hover round it till the dawn of the great day, when all the armies shall be marshaled into line again, when the wars of time shall cease, and the great eternity of peace shall commence.

Two prisoners of Johnson’s Island were released by order of President Abraham Lincoln, issued on December 10, 1864. The Tennessee men were released after their wives appealed to the President, one pleading her husband’s case on the basis that he was a religious man.

When the President ordered the release of the prisoners, he said to this lady: “You say your husband is a religious man; tell him when you meet him that I say I am not much of a judge of religion, but that, in my opinion, the religion that sets men to rebel and fight against their Government because, as they think, that Government does not sufficiently help some men to eat their bread in the sweat of other men’s faces, is not the sort of religion upon which people can get to heaven.”

Berrien Minute Men Second Lieutenants James A. Knight and Levi J. Knight, Jr. arrived at the prison on December 20, 1864; They were captured at Franklin, TN on December 16.

December 22, 1864 was snowy, windy and bitter cold at Johnson’s Island. New arrivals at the prison on that day included Col. William D. Mitchell, 29th, GA Regiment; Lacy E. Lastinger; 1st Lieutenant Thomas W. Ballard; Captain Robert Thomas Johnson, Company I, 29th Regiment, arrived at the prison. Lastinger, 1st Lieutenant from Berrien Minute Men, Company K, 29th GA Regiment and Ballard, Company C, 29th GA had been captured December 16, 1864 at Nashville, TN. Other arriving prisoners from the 29th GA Regiment included 2nd Lieutenant Walter L. Joiner, Company F.

Edwin B. Carroll and the other prisoners passed Christmas and New Years Day on Johnson’s Island with little to mark the occasion. By February 1865, Confederate POWs at Johnson’s Island were being exchanged for the release of Federal POW’s imprisoned in the South.

On March 29, Major Lemuel D. Hatch wrote from Johnson’s Island,

For several months we suffered here very much for something to eat, but all restrictions have now been taken off the sutler and we are living well… The extreme cold of last winter and the changeableness of the climate has been a severe shock to many of our men. I notice a great deal of sickness especially among the Prisoners captured at Nashville. Nearly all of them have suffered with rheumatism or pneumonia since their arrival.

The end of the war came with Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865 and, for Georgians, the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate Army to General William T. Sherman at the Bennett Place, April 26, 1865.

After spending almost a year in the Johnson’s Island prison, Edwin B. Carroll was released in June 1865.

To leave Johnson’s Island a prisoner was required to take an Oath of Allegiance to the United States, as by accepting Confederate citizenship they had renounced their citizenship in the United States. The Confederate prisoners called taking the oath “swallowing the eagle,” and men who swore allegiance to the United States were called “razorbacks,” because, like a straight-edged razor, they were considered spineless.

The prisoner had to first apply to take the Oath. He was then segregated from the prison population and assigned to a separate prison block. This was done for the safety of those taking the Oath as they were now repudiating their loyalty to the Confederacy. Until 1865, only a small number of prisoners took the Oath because of their fierce devotion and loyalty to the cause for which they were fighting. However, in the Spring of 1865, many prisoners did take the Oath, feeling the cause for which they fought so hard was dead. The following letter written by prisoner Tom Wallace shows that “swallowing the eagle” (taking the oath) was not done without a great deal of soul searching. http://johnsonsisland.org/history-pows/civil-war-era/letters-to-and-from-confederate-prisoners/

Tom Wallace, 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Kentucky Regiment wrote from Johnson’s Island in 1865 about taking the Oath of Allegiance:

My dear mother,

Perhaps you may be surprised when I tell you that I have made application for the “amnesty oath”. I think that most all of my comrades have or will do as I have. I don’t think that I have done wrong, I had no idea of taking the oath until I heard of the surrender of Johnston and then I thought it worse than foolish to wait any longer. The cause that I have espoused for four years and have been as true to, in thought and action, as man could be is now undoubtedly dead; consequently I think the best thing I can do is to become a quiet citizen of the United States. I will probably be released from prison sometime this month

Edwin B. Carroll swore the Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America on June 14, 1865 at Depot Prisoners of War, Sandusky, OH. He was then described as 24 years old, dark complexion, dark hair, hazel eyes, 5’11”

When the War ended, and he returned home, he could find no employment but teaching, in which he has been engaged almost every year since… In October, 1865, he was married to Mrs. Julia E. Hayes, of Thomasville, Georgia.

Related Posts:

![April 1863 newspapers reported food shortages, hoarding and profiteering in Savannah, GA (Lancaster Gazette [Enland], April 18, 1863)](https://raycityhistory.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/1863-4-18-lancaster-gazette-savannah-food-shortage.jpg?w=477)