In 1932, James Nicholas Talley, a son of Berrien County, GA and member of the Macon Bar, published a dramatic account of court proceedings that occurred in the 1840s in Troupville, county seat of old Lowndes County, Georgia. Samuel Mattox, son of Aaron Mattox, was charged in the September 7, 1843 murder of William Slaughter. The Studstill brothers, Jonathan and Emanuel “Manny” Studstill, sons of Rachel Sirmans and Hustus Studstill (aka Eustus Studstill), were also implicated in the crime. In 1836, Samuel Mattox had been the first to discover Indians were active in then Lowndes county near Ten Mile Creek, prior to the Battle of Brushy Creek. Ten Mile Creek, the locality of the Slaughter murder, lies slightly northeast of present day Ray City, GA.

Talley’s narrative of the murder of the Slaughter boy and the trials that ensued are transcribed below, along with contemporaneous news clippings of the events and other supplemental information.

AN ANTEBELLUM TRIAL AT TROUPVILLE

By J. N. TALLEY, of the Macon Bar

Late in the afternoon of September seventh, Eighteen Forty-three, a fifteen-year-old boy, William Slaughter, rode through the pine woods near Ten Mile creek. He was driving up a herd of cattle, for it was milking time at his father’s pioneer settlement in the upper part of Lowndes.

At a distant clearing, the calves having been rounded up and penned, Samuel Mattox and his wife, Rachel, the milker, stood at the pasture bars. With them were two young men of the neighborhood, Jonathan Studstill and his brother, Manuel, who had come over to see Mattox and make plans for an early deer hunt. While they were waiting somewhat impatiently for the cows, Manuel displayed a gun which he had brought along, a rifle so rusty and antiquated in pattern that he declared, to the amusement of the group, it wouldn’t kill a steer at fifteen steps. They were “all in a laugh,” when the straggling herd, guided by the mounted boy, came into sight a quarter of a mile away.

The ford was soon reached, but there horse and rider stopped and, scattering out over a wiregrass level, the cows began to graze.

Observing from the calf lot this delay at the ford, Jonathan with a loud halloo ordered the boy to “come on.” William doubtless did not hear the command, for he continued to await the arrival of a brother from across the creek. From his stand by the fence, possibly actuated by the instinct of the hunter, perhaps-for no reason at all, Mattox closely contemplated the distant youthful figure in the fading light dimly outlined against the dense foliage of the swamp. While Mattox was so engaged, Manuel handed him the rifle and suggested that he shoot. Jonathan likewise said “shoot,” adding that the old firearm wouldn’t hit the side of a house. “Moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil”, as was afterwards charged, Mattox took aim and sighted, first however, it is said, deliberately resting the rifle barrel on a heap of brush. “Stop” screamed Rachel, but the shot rang out, and through the clearing smoke the unoffending lad was seen to fall from his saddle.

Dropping the gun and leaving Rachel at the pasture bars, the men ran to the ford and found the stricken boy. Horrified they discovered that the ball, speeding with unexpected force and accuracy, had penetrated his skull. Realizing that the report of the gun had carried far and thinking to avert suspicion, Jonathan and Mattox roughly pressed a pine stick through the open wound into the substance of the brain. Upon receiving this shock, the prostrate and apparently lifeless form arose and for one awful moment stood, face distorted by pain and wide unseeing eyes fixed upon Jonathan. Seizing the horse, which had remained standing by its unconscious master, Manuel rode away to summons help. Later when Samuel Slaughter, the brother, and [Captain John] Sanderson, a neighbor arrived, and the mother came up in her cart, they were told by Mattox and Jonathan how a random shot fired from across the creek had frightened the horse, how the boy had been violently thrown, and how in falling his head struck a pine knot. Pointing to the stick, Jonathan declared to the mother, “that snag proved your son’s death.”

Early next morning young Slaughter died. The locality where he was shot is still known locally as Slaughter’s Ford and is some five or six miles from the present town of Nashville in Berrien county.

Cause of Death Revealed by Hole in Hat.

The remote rural community had been thoroughly aroused. Samuel Slaughter, who heard the shot, maintained that it came from the direction of the calf pen, for at the time he himself had been “across the creek.” The Studstills, Mattox and Rachel did much talking, and after several days Mattox acknowledged that it was he who fired the “random shot” which frightened the horse. The theory of accidental death was being generally accepted until one day Moses Slaughter at home took down his son’s hat and found a hole, clear cut and evidently made by a bullet. Then Sanderson, who had removed the stick, remembered that instead of being jammed it was loose and moved with the pulsations of the brain. The body was disinterred, a post-mortem made by Dr. Briggs of Troupville, and a rifle ball found imbedded in the left side of the head.

A Warrant issued for the arrest of Mattox, who promptly sought refuge in the thickets about a secluded pool, afterwards called “the Mattox pond,” and now crossed by State Highway No. 11.

At this point in J. N. Talley’s story we can add that Samuel Mattox was captured and taken to Troupville, GA where he was incarcerated in the county jail. During this time the Jailor in Troupville was Morgan Swain, who was also a blacksmith and innkeeper. Swain’s Hotel was favored by courtgoers, amicus curiae, and the just plain curious who flocked to town on court days.

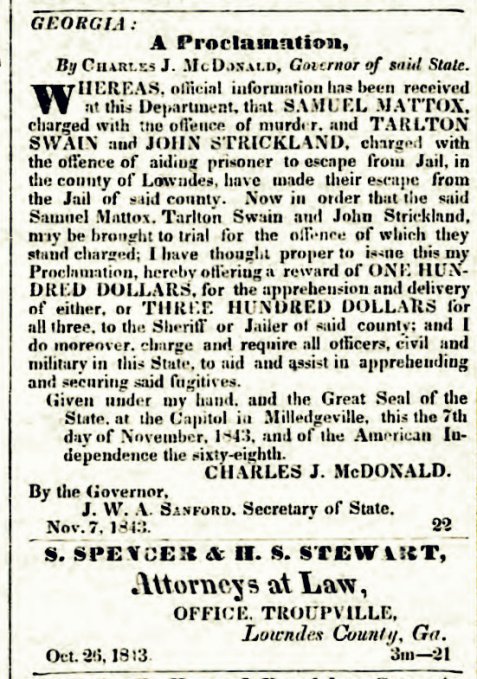

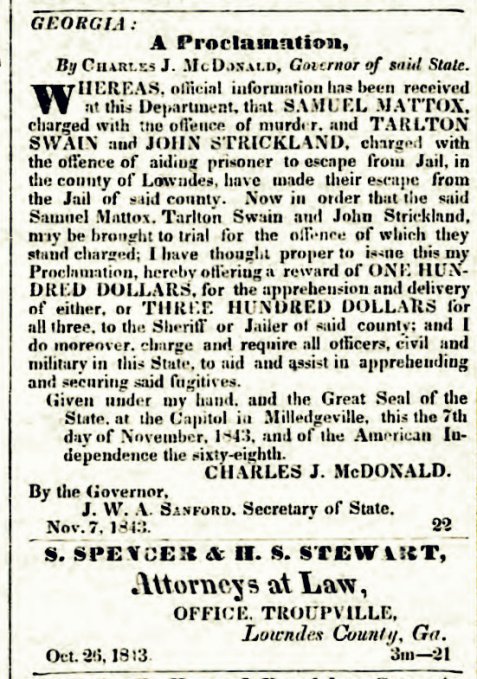

As it happened, Mattox was held with cellmates Tarlton Swain and John Strickland. Tarlton “Talt” Swain was the brother of Morgan Swain, and whereas Morgan represented law and order, Talt Swain and his posse were the community Bad Boys. It is said that Talt not being of a mind to take chances with a court trial, effected an escape. The Milledgeville Federal Union reported the fugitives’ flight and the Governor’s offer of reward for their capture:

Federal Union, Nov. 21, 1843 — page 1

GEORGIA:

A Proclamation

By Charles J. McDonald, Governor of said State.

Whereas, official information has been received at this Department, that SAMUEL MATTOX, charged with the offence of murder, and TARLTON SWAIN and JOHN STRICKLAND, charged with the offence of aiding prisoner to escape from Jail, in the county of Lowndes, have made their escape from the Jail of said county. Now in order that the said Samuel Mattox, Tarlton Swain and John Strickland, may be brought to trial for the offence of which they stand charged; I have thought proper to issue this my Proclamation, hereby offering a reward of ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS, for the apprehension and delivery of either, or THREE HUNDRED DOLLARS for all three, to the Sheriff or Jailer of said county; and I do moreover, charge and require all officers, civil and military in this State, to aid and assist in apprehending and securing said fugitives.

Given under my hand, and the Great Seal of the State, at the Capitol in Milledgeville, this the 7th day of November, 1843, and of the American Independence the sixty-eighth.

CHARLES J. McDONALD.

By the Governor,

J. W. A. Sanford, Secretary of State,

Nov. 7 1843.

The Governor’s offer of a reward was issued by Georgia Secretary of State John William Augustine Sanford. Sanford had been prosecutor Augustin H. Hansell‘s commanding officer in the Indian Wars of 1836.

It is interesting to note that the legal classified advertisement following the reward announcement above was for the law offices Samuel Spencer and H. S. Stewart. Spencer’s presence in Troupville, or the lack thereof, would figure prominently in later court proceedings during the trial of Jonathan Studstill.

Mattox was apparently captured in a timely manner and remanded back to the jail at Troupville to stand trial.

Resuming the account by J.N. Talley:

Mattox Convicted

At Troupville, Mattox was put on trial for his life, convicted, and sentenced to death. The many vital questions argued by counsel were finally decided by the then highest judicial authority, a superior court judge, for there was no supreme court, and no appeal.

New York Herald, June 24, 1844. Samuel Mattox convicted of murder in Lowndes County, GA.

The execution took place in July (probably 1844) on a hill just east of the Withlacoochee river, and was conducted by sheriff John Towels, who happened to be an intimate friend of the victim. The hanging was witnessed by a crowd said to have been the largest, with one exception, ever assembled at Troupville, the exception being a circus in the late 50’s which for all time set an attendance record at Lowndes’ antebellum capital.

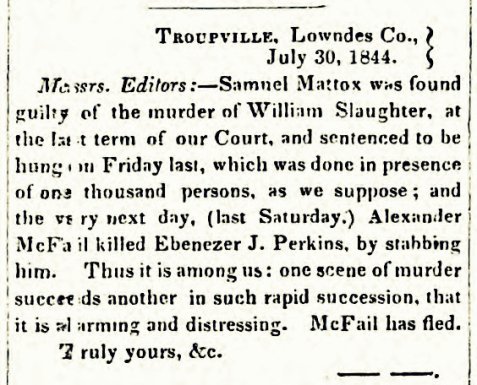

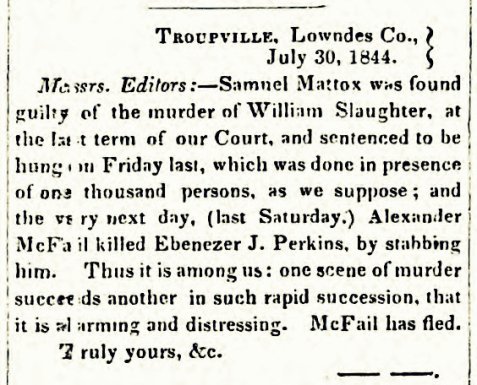

1844 Hanging of Samuel Mattox at Troupville, GA was reported in the Milledgeville Southern Reporter, August 13, 1844 edition.

Milledgeville Southern Reporter

August 13, 1844

Troupville, Lowndes Co.,

July 30, 1844.

Messrs. Editors: – Samuel Mattox was found guilty of the murder of William Slaughter, at the last term of our Court, and sentenced to be hung on Friday last, which was done in presence of one thousand persons, as we suppose; and the very next day, (last Saturday.) Alexander McFail killed Ebenezer J. Perkins, by stabbing him. Thus it is among us: one scene of murder succeeds another in such rapid succession, that it is alarming and distressing. McFail has fled.

Truly yours, &c.

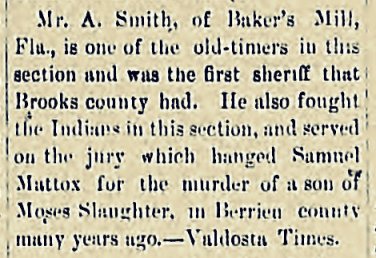

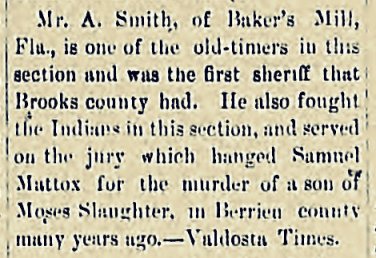

J. N. Talley noted in his narrative that, “The records of the Mattox trial were destroyed when the courthouse burned in June, 1858.” From later news clippings, we know that one of the jurors was Ajaniah Smith, who later moved to Baker’s Mill, FL.

Tifton Gazette, March 8, 1901 clipping indicates Ajaniah Smith served on the jury at the trial of Samuel Mattox in 1844.

Tifton Gazette

March 8, 1901

Mr. A. Smith, of Baker’s Mill, Fla., is one of the old-timers in this section and was the first sheriff that Brooks county had. He also fought the Indians in this section, and served on the jury which hanged Samuel Mattox for the murder of a son of Moses Slaughter, in Berrien county many years ago. – Valdosta Times.

Talley documents that in the matter of the murder of William Slaughter the legal proceedings were an incredibly drawn out affair, stretching over a seven year period. His narrative picks up in 1848 with the trial of Jonathan Studstill, who allegedly aided and abetted the murder of Slaughter.

The Studstill Case

The Studstill brothers had been indicted for murder in the second degree, a capital felony. The charge against them was not tried until 1848, five years after the crime had been committed. Throughout this long period Jonathan languished in Troupville’s little jail near the banks of the Withlacoochee. In the meantime Rachel Mattox had become Rachel Bailey. This comely, young woman seemed dogged by the spectre of crime. Her second husband [Burrell Hamilton Bailey] some years later was also tried for murder, but found not guilty. (SEE Showdown in Allapaha and The State vs Burrell Hamilton Bailey)

Troupville in 1848, boasted of three hotels and four lawyers. The resident bar, normally adequate for local needs, was more or less eclipsed by the semi-annual advent of the circuit riders. These perambulatory dignitaries, traveling in gigs and sulkies or on horseback, that year had begun their ”Fall’ riding at Dublin on the first Monday in September.

An Old Indictment

The following indictment had been returned against Jonathan and Manuel Studstill:

GEORGIA, LOWNDES COUNTY.

The Grand Jurors, etc., in the name and behalf of the citizens of Georgia, charge and accuse Manuel Studstill and Jonathan Studstill, both of the County and State aforesaid, with the offence of murder, as principals in the second degree. For that one Samuel Mattox, not having the fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil, on the 7th day of September, 1843, with force and arms in the County aforesaid, in and upon one William Slaughter, in the peace of the State then and there being, feloniously, unlawfully, wilfully, and of his malice aforethought, then and there did make an assault, and that he, the said Samuel Mattox a certain rifle gun of the value of twenty dollars, the property of Manuel Studstill, then and there being found, the said rifle gun being then and there charged with gunpowder and a leaden bullet, which rifle gun he, the said Samuel Mattox, in both his hands then and there had and held at, against and upon him, the said William Slaughter, then and there feloniously, unlawfully, and of his malice aforethought, did discharge and shoot off; and that he, the said Samuel Mattox, with the leaden bullet aforesaid, by force of the gunpowder aforesaid, so by him, the said Samuel Mattox as aforesaid, discharged and shot off, him, the said William Slaughter, in and upon the left side of the head of him, the said William Slaughter, then and there feloniously, unlawfully, wilfully, and of his malice aforethought, did strike and wound, giving to the said William Slaughter, then and there, with the leaden bullet aforesaid, out of the said rifle gun, so as aforesaid discharged and shot off, in and upon the said left side of the head of him, the said William Slaughter, one mortal wound of the breadth of one inch and depth of two inches, of which said mortal wound he, the said William Slaughter, on and from the said 7th day September, in the year aforesaid, until the 8th day of September, in the year aforesaid, at the house of one Moses Slaughter, in the County aforesaid, did languish, and languishing did live, on which said 8th day of September, in the year aforesaid, about the hour of nine o’clock, in the morning, he, the said William Slaughter, at the house of said Moses Slaughter, in the County aforesaid, of the mortal wound aforesaid, died.

And the jurors aforesaid, on their oaths aforesaid, do say, that the said Manuel Studstill and the said Jonathan Studstill, on the said 7th day of September, in the year aforesaid, in the County and State aforesaid, then and there feloniously, wilfully, unlawfully, and of their malice aforethought, were present, aiding helping, abetting, comforting, assisting and maintaining the said Samuel Mattox in the felony and murder aforesaid, in manner and form aforesaid, to do and commit, contrary to the laws of said State, etc.

This indictment language, convoluted and legally flawed as it was, became an exemplar of indictments, and was cited in legal forms encyclopedias for decades afterwards. Although the Lowndes court records of this trial were also lost in the courthouse fire of 1858, we know from other court records that the foreman of the jury was Thomas M. Boston.

The Court Room

The State against Manuel and Jonathan Studstill, murder, was sounded for trial at the December term, 1848. The small scantily furnished court room was crowded. Within the bar a dozen or more lawyers occupied cowhide bottom chairs irregularly arranged behind plain pine tables. These tables supported sundry well-worn but highly prized volumes of law, a nondescript collection of ink wells and quill pens, and numerous resplendent stove pipe hats carefully deposited upside down. Trained under his uncles, Eli and Lott Warren, the presiding judge James Jackson Scarborough had become one of the outstanding lawyers of two circuits. His reputation at the bar, however, it is said, was surpassed by that which he attained while on the bench, and “there was a child-like simplicity about him which blended with his legal acumen and judicial ability made him a refreshing character.” Augustin H. Hansell, solicitor general, appeared for the prosecution. The following year he was to succeed Scarborough as Judge of the Southern Circuit, a station which he occupied and conspicuously adorned during forty-three years. To assist in the prosecution had been retained Samuel Rockwell, rich in garnered experience and gifted in forensic oratory. On behalf of the Studstills appeared the learned Carlton B. Cole, twice judge of the Southern Circuit and destined in after years to preside over the courts of the Macon Circuit, and with Clifford Anderson and Walter B. Hill to form the first faculty of the Law School at Mercer University.

According to J. T. Shelton’s Pines and Pioneers, Carlton B. Cole was assisted by Peter Love, John J. Underwood, Clark, and Samuel Spencer.

Procedure Reviewed

The State being ready, the first motion came from the defendants who asked for a severance and that they be tried separately. This granted, Hansell announced that Manuel’s case would be taken up first. Cautiously refraining from announcing that Manuel was ready for trial, Cole informed the court of a pending plea of autrefois acquit. Issue being joined, there was a complete trial, which ended in a verdict against the plea. Thereupon Hansell announced that the State elected to put Jonathan on trial. This unexpected action was vigorously protested by Cole who insisted that the prosecution could not abandon the case on trial and take up that of Jonathan; Judge Scarborough held, however, that the disposition of the plea was merely the removal of an obstacle out of the way and not a part of the main trial, and directed Jonathan to plead. Cole now moved for a continuance of Jonathan’s case on account of the absence of Samuel Spencer, a member of the Thomasville bar, who was then at Tallahassee in attendance on a meeting of the Presidential Electors, the first to be held in the new state of Florida. In support of this motion it was shown that one [William] Holliday had been subpoenaed by the State for the purpose of proving that in a conversation Jonathan had confessed his guilt. Spencer was expected to testify that Holliday afterwards admitted being “so beastly drunk” on the occasion in question as to have been utterly incapable of understanding the conversation or anything else. The motion was overruled, but the prudent Hansell during the trial was careful not to call Holliday as a witness, thus avoiding the effect of a favorable ruling which might constitute reversible error. These preliminaries disposed of, at a word from his attorney, Jonathan slowly walked to the prisoner’s dock and awkwardly stood there for arraignment and plea. Already knowing what the State held against him, the prisoner soon tired of listening to the verbose indictment, and turned his gaze straight to a window by the judge’s bench. There, beyond the moss draped trees fringing the Withlacoochee he saw the very hill where a few years before an enormous crowd had gathered to make of Mattox’ hanging a Roman holiday.

With jury in the box the stage was set for the trial of Jonathan’s case upon its merits.

The Trial Proceeds

The attention of all in the court room centered upon Augustin H. Hansell as he arose to open the case for the State. In appearance the young solicitor general was tall and strikingly handsome, clean shaven, his abundant hair worn rather long as was the fashion, and his dress, that affected by gentlemen of his profession – dark frock coat, trousers neatly fitting over high boots, waistcoat of gaily flowered silk, surmounted by the folds of a black stock sharply contrasting with his gleaming linen. The prosecuting attorney told the jury that if the State produced that proof the nature of which he had outlined, it would be their duty to find Jonathan guilty.

Before any evidence was submitted, the dignified Cole, addressing the judge, stated that even if the State’s proof should measure up to the expectations of the learned solicitor general, yet the jury would be bound to acquit the prisoner, and moved the court for a directed verdict of not guilty. It was pointed out by Cole that although the indictment charged Jonathan with murder in the second degree, it nowhere directly charged Mattox, the principal, with the offense of murder. While the offense had been described in the body of the indictment, nevertheless, argued Cole, there was at its conclusion no express allegation that Mattox had murdered the deceased, and that the omitted expression, technical though it was, could be supplied by no other. 2 Hawk. Pl. Cr. 224.

The attorneys for the State could not controvert the proposition that this objection to the indictment was fatal at common law. They contended, however, that the rule laid down did not apply to a principal in the second degree, but could find no authority. Driven from the principles and precedents of the cherished common law, the prosecution was reluctantly forced to fall back upon that section of the penal code of 1833, which provided that every indictment shall be deemed sufficiently technical which states an offense in the language of the code or so plainly that the nature of the offense may be understood by the jury. Prince 658.

Notwithstanding the indictment was an imperfect specimen of the draughtsman’s art, yet its meaning being understandable, the judge was constrained to overrule the motion.

Over the objection of the defendant, the indictment against Mattox, together with verdict and judgment and certain confessions made by him, were offered in evidence by the State, and then from the stand was narrated the story of how the boy while driving up his father’s cattle had been shot at the ford on Ten Mile Creek.

Rachel, the chief witness for the prosecution, and perhaps the only woman in the crowded court room, found herself in a trying situation. On the one side was fixed upon her the stern gaze of the unrelenting old pioneer settler, and on the other she beheld the kindly pleading eyes of Jonathan, friend of her former husband. Under these circumstances she clung to the anchor of remembered truth and testified that she heard Jonathan and Manuel tell Mattox to shoot, that the gun wouldn’t hit a boy at fifteen steps, but that she did not know whether her husband took aim or fired at random. Opposing her statement was that of Manuel who said he did not hand Mattox the gun, that so far as he saw or heard, his brother had nothing to do with the killing, and that he did not hear Rachel tell Mattox not to shoot,

The evidence concluded, on the law Cole argued that because of the great distance, the killing was not a probable consequence of the negligent act, therefore, the homicide was reduced to involuntary manslaughter as to which there could be no principal in the second degree. The State, however, contended that since the shooting itself was an unlawful act, the defendant was guilty, if the killing was even a possible consequence.

Argument Long and Loud

As soon as the first outburst of impassioned eloquence put the village on notice that jury speaking had begun, men came running from the square, the groceries, the taverns, and stables, and soon taxed the capacity of the courtroom. The anticipation of this probable consequence, it may be remarked without impropriety, did not prevent the aforesaid outburst from being made both early and loud, for it should be remembered that in those days the perambulatory attorney usually had in mind not only the case in hand but two others in the bush, and frequently also political preferment in the offing.

To most of those present, the jury speaking, which embraced argument, anecdote, pathos, oratorical flights, and sharp clashes between counsel, was the high point of the semi-annual entertainment presented by the court. The distinguished and resourceful antagonists no doubt made free use of all the material afforded by the case on trial, and we may imagine how in the disputation poor Rachel was bandied and buffeted back and forth – now thrown down as weak, simple, dominated, untrustworthy – now exalted as a paragon of unswerving truth and womanly virtue.

In his charge Judge Scarborough no doubt “summed up” the testimony as is still done in the United States Court, and may have expressed his opinion. Certain it is, the Judge stated to the jury if Rachel swore the truth the defendant was guilty. In view of the hard circumstances of this unusual case and the prominence given her testimony, it is not unlikely the jury conceived the practical question to their determination to be, Did Rachel swear the truth? Since an effort at her impeachment had miserably failed, it was perhaps, easy for them to conclude that she was a truthful witness, and, therefore, to decide, as they did, that Jonathan was guilty of murder.

The pageantry of the trial over, its excitement and suspense ended, a wave of sympathy appeared to move the hushed crowd of curious onlookers. As they heard the fearsome pronouncement of the judge, interrupted only by the stifled sobs of Rachel, and saw Jonathan standing at the bar, with his staring gaze fixed upon the barren hilltop beyond the Withlacoochee.

Conviction Affirmed

The conviction was affirmed by the Supreme Court sitting at Hawkinsville at the June Term, 1849. Studstill vs. State 7 Ga. 2.

In sustaining Judge Scarborough’s ruling that the indictment was good, although it did not meet the technical requirements of the common law, Justice Joseph Henry Lumpkin used the following language:

“The age is past for the civil and criminal justice of the country to be defeated by the absence or presence of one or more ‘absque hocs,’ ‘then and theres,’ videlicts,’ etc. And for one, I rejoice to see edifices built, although they may be ‘with the granite of Littleton, the cement of Coke, the trowel of Blackstone, and the Masonic genius of a hundred Chief justiciaries, and covered with the moss of many generations,’ swaying beneath the sturdy blows so unsparingly applied by the hand of reform. Why should the spirit of progress which is abroad in the World, and which is heaving and agitating the public mined in respect to the arts, sciences, politics and religion, halt upon the vestibule of our temples of justice? Why not penetrate tearlessly, the precincts of the Bar and Bench, and remodel the principles and practice of the old common law, to accommodate it to the enlightenment of a rapidly advancing civilization? Our courts should co-operate cordially with the Legislature in building up a modernized jurisprudence, upon the broadest foundations.” _Studstill vs. State, 7 Ga. 2.

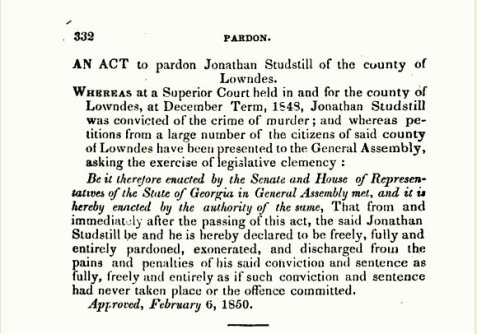

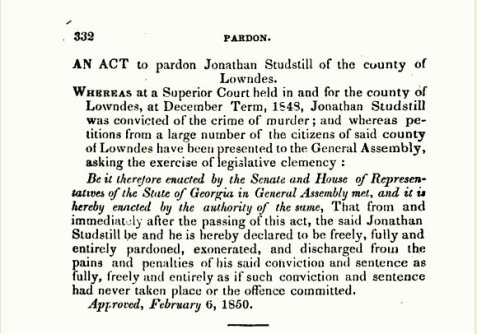

Jonathan Receives Pardon

By an act approved February 6, 1850, the General Assembly granted to Jonathan Studstill a pardon and declared him entirely exonerated and discharged from the pains and penalties of his conviction and sentence “as fully, freely and entirely as if such conviction and sentence had never taken place or the offense committed.”

After this disposition of Jonathan’s case, apparently the prosecution against Manuel was abandoned.

Pardon of Jonathan Studstill, Acts of the State of Georgia 1849-50.

AN ACT to pardon Jonathan Studstill of the county of Lowndes.

Whereas at a Superior Court held in and for the county of Lowndes, at December Term, 1848, Jonathan Studstill was convicted of the crime of murder; and whereas petitions from a large number of the citizens of said county of Lowndes have been presented to the General Assembly, asking the exercise of legislative clemency:

Be it therefore enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the State of Georgia in General Assembly met, and it is hereby enacted by the authority of the same, That from and immediately after the passing of this act, the said Jonathan Studstill be and he is hereby declared to be freely, fully and entirely pardoned, exonerated, and discharged from the pains and penalties of his said convictions and sentence as fully, freely and entirely as if such conviction and sentence had never taken place or the offence committed.

Approved, February 6, 1850.

∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

The Dumb Act

It is significant that the same legislature passed a statute, approved February 21, known as “the Dumb Act of 1850,”which made it unlawful for any superior court judge in his charge to the jury to express or intimate his opinion as to what has or has not been proved or as to the guilt of the accused. There was at the time a considerable sentiment in favor of curbing the judiciary, but the Studstill case was probably one of the leading factors which crystallized that sentiment in Georgia.

The bill which became known as the Dumb Act was introduced by Richard H. Clark, then a senator living at Albany. Incidentally it is interesting to note that the author of the bill himself subsequently occupied the judicial station for twenty-two years. We are told this distinguished jurist would sometimes lose sight of the restraints thrown around the judge by our peculiar system of jurisprudence and appear to invade the province of the jury, and that most of the reversals of his judgment by the supreme court were based upon exceptions to alleged expressions of opinion before the jury. 99 Ga. 817

Judge Clark was familiar with the Studstill case, and in 1876 he referred to it as “one of the most interesting cases in the judicial annals of the State.” (58 Ga. 610).

Old Troupville

Lowndes County in 1843, when young Slaughter was killed, lay between Thomas and Ware, extended from the Florida line northward ninety miles, and was very sparsely settled. Its first county seat Franklinville, on the Withlacoochee two miles west of Cat Creek, had been abandoned ten years before and a permanent capital established at Troupville, a village situated in the angle formed by the confluence of the Little and Withlacoochee rivers, some six miles distant from the site of the present city of Valdosta.

At the time of the Studstill trial in 1848 Troupville was still a small village the next decade however, being a gateway to the new state of Florida, and supposed to be on the line of a projected railroad from Savannah, its growth was almost phenomenal. At one time its bar consisted of thirteen members. Its newspaper The South Georgia Watchman, was the predecessor of the Valdosta Times.

When attending court, the judge and lawyers usually stopped at a tavern widely famed for its hospitality and presided over by a genial host, who was affectionately called “Uncle Billy Smith”. Across the street from the inn was the public square. On this was situated not only the court-house and jail, but also the stables belonging to the stage line and a convenient “grocery”.

The orderly decorum of the court room at Troupville was occasionally disturbed by energetic but short-lived fist fights on the square, but another disturbance occurring periodically had the more serious effect of halting the court. This was preceded by the shrill blasting of a bugle, followed by the measured“ beat of galloping horses and the loud, reverberations of the lumbering stage coach from Thomasville, as it rattled across the boards of Little River bridge. The forced recess continued until the stage with four fresh horses crossed over the Withlacoochee bridge and departed on its long journey through the pines to Waresborough.

A source of interruption within the court room itself was the practice of having grand jury witnesses sworn in open court. From time to time, more or less inopportune, a grand juror escorting two or three witnesses would appear at the bar, where upon the business in hand was suspended until the oath could be administered. These interjected proceedings were narrowly watched, and not infrequently a bystander, whose conduct was about to be investigated would be seen to make a hurried departure for the purpose of securing temporary immunity from punishment should the grand jury return a presentment.

The general complexion of a court crowd in those times differed somewhat from that of the post bellum period in that the black population remained at home, excepting the family coachman. These privileged and interesting characters contributed their bit to entertain the transients on the square, while their influential masters within the courtroom occupied chairs and hobnobbed with the dignitaries of bench and bar.

Court Week always attracted a great concourse of people. Some attended from necessity or compulsion, some to enjoy the feast of erudition and eloquence; others to trade, traffic or electioneer, but to many it was an occasion for much drinking and horse swapping, and for indulgence in cock fighting, horse racing, and other “Worldly amusements” for which Troupville became somewhat notorious. Indeed, among the Godly, it was regarded as a wild town – almost as wicked as Hawkinsville.

A Vanished Town

Now beneath a spreading oak that shades the old Stage road, a granite marker points out to passers-by the place where once stood Troupville – the far famed capital of Lowndes.

Only the rivers there remain, eternally the same –

Black waters, musically slipping,

Whose ripples sway the gray moss dipping

From hoary overhanging, trees

That murmur to the whispering breeze

Old tales of ancient memories.

-30-

Related Posts: