An Otranto Funeral in Belfast

Perhaps no county paid a greater toll in WWI than Berrien County, Georgia. Twenty-three of her young men perished in the sinking of the H.M. S. Otranto just weeks before the war ended.

When survivors of the Otranto shipwreck were ferried by the H.M.S. Mounsey to Belfast, Ireland the American Red Cross was there waiting for their arrival. James Marvin DeLoach, with many Ray City GA, connections, and James Grady Wright of Adel, GA, Henry Elmo DeLaney of Nashville, GA and Ange Wetherington were among nearly 450 men who had managed to leap from the rails of the Otranto to the deck of the rescue ship Mounsey and were landed in Belfast.

A hundred and fifty of the survivors had been badly injured in the jump, the injuries ranging from split skulls to broken ribs, broken legs and the like. On the decks of the dangerously overloaded Mounsey, the men clung for their lives to whatever handholds they could grab. Many suffered from exposure on the trip to Belfast, some perished. Others contracted pneumonia and died after reaching Belfast.

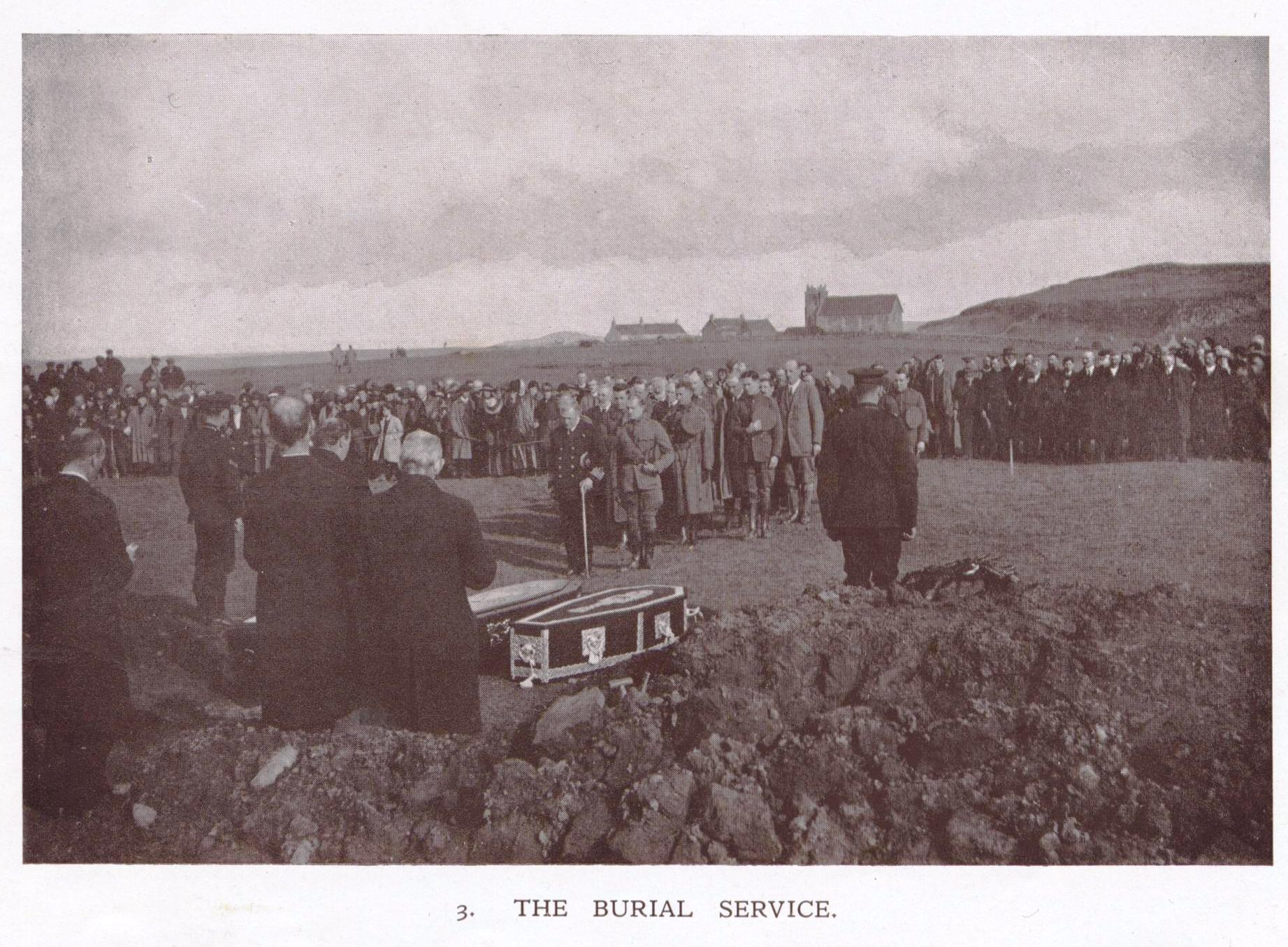

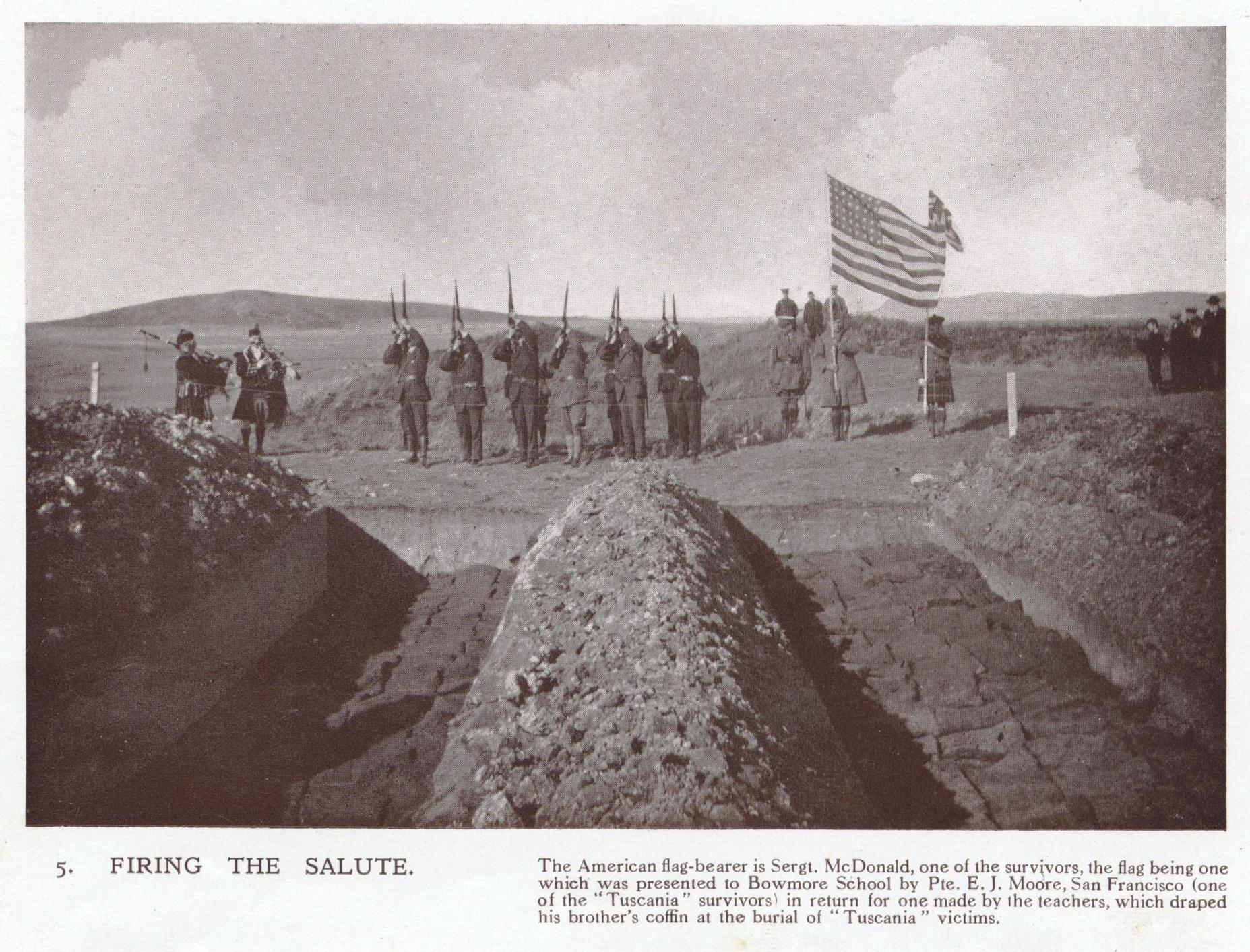

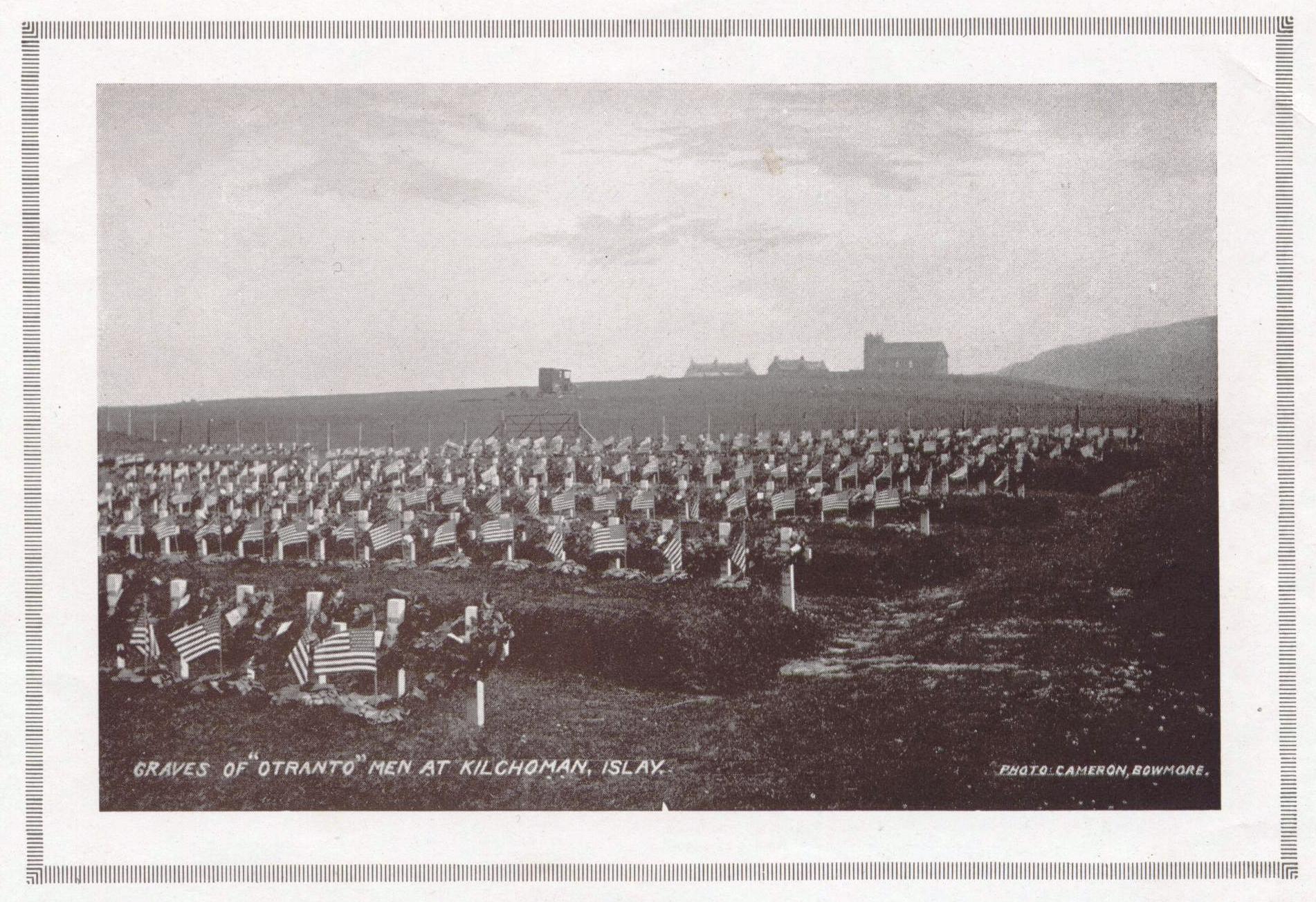

Most of the hundreds of soldiers who were left behind on the Otranto perished in the sea. A scant 17 managed to survive the swim to the rocky coast of Islay, Scotland, among them Early Stewart of Berrien County, GA. For the hundreds of dead who washed ashore, two funerals were held on Islay.

A Third funeral for American soldiers from the Otranto occurred at Belfast, Ireland on October 11, 1918. Seventeen of the men of the Otranto were interred in the city cemetery in Belfast, victims of the Otranto Disaster and men who had died from Pneumonia after reaching Belfast. Belfast stopped in respect as the funeral procession passed from the Victoria barracks, through Royal Ave, to the City Cemetery. Everywhere the streets were crowded with people who gathered to pay tribute to the honored dead. The flag-draped coffins were carried on open hearses, two on each conveyance, with a guard of honor composed of British soldiers marching alongside. There were many floral wreaths, sent by the American Red Cross, the Belfast Care Committee, and other Belfast civic organizations. The band of mourners who marched behind the coffins included the Lord Mayor of Belfast, the American Consul, and representatives of the American and British army and navy, the Red Cross, and various local civic organizations.

An American military funeral in Belfast, Ireland. On Oct. 11, twelve American soldier victims of the Otranto Disaster and men who had died from Pneumonia after being landed from a troopship were buried in the City Cemetery. The photograph shows the funeral procession passing through Royal Ave. The wreaths shown in the picture were chiefly gifts of the Belfast Care Committee of the American Red Cross http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10185a

†††

An American military funeral in Belfast, Ireland. On Oct. 11, a public funeral was held in Belfast for twelve American soldiers, victims of the Otranto disaster, and men who died from pneumonia after being landed in Ireland. The march through the city, from the Victoria barracks to the City Cemetery. Everywhere the streets were crowded with people who had gathered to pay tribute to the honored dead. The coffins were carried on open hearses, two on each conveyance, with a guard of honor composed of British soldiers, marching beside the coffins, each of which was covered with an American flag

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10184a

†††

British soldiers escorting American flag draped coffins

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.01511a

†††

†††

An American military funeral in Belfast, Ireland. On Oct. 11, twelve American soldiers, victims of the Otranto and also several pneumonia cases, were buried in the City Cemetery. British soldiers formed the guard of honor for the coffins, as they were carried through the principal streets of Belfast. The photograph shows the procession entering the gates of the cemetery

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10187a

†††

†††

An American military funeral at Belfast, Ireland. Burying a Coffin. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.01512

†††

An American military funeral at Belfast, Ireland. The buglers sound the last salute to the dead. The graves are those of American soldiers from the sinking troopship HMS Otranto who died of injuries received in the rescue, or of pneumonia in Belfast hospitals, after being landed.

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10189a

7

An American military funeral at Belfast, Ireland. Firing squad from the British army (Northumberland Fusiliers) fires the last salute at the graveside. The funeral was of twenty American soldiers on Oct. 11. Part of the men were victims of the Otranto disaster; others were men who died of pneumonia in Belfast hospitals shortly after arriving in Europe http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10190a

†††

A Third funeral for American soldiers from the Otranto occurred at Belfast, Ireland. The men interred in the city cemetery in Belfast, there were many floral wreaths, sent by the Red Cross and by Belfast civic organizations. On this occasion, one of the finest was inscribed “A token of esteem and sympathy from their comrades of the British army” http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.10121a

†††

†††

City Cemetery, Belfast, Ireland; American soldiers graves

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/anrc.01521a

†††

New York Times

October 29, 1918BIDDLE THANKS BELFAST.

General Acknowledges the Funeral Honors to Otranto Victims.

Special Cable to the New York Times.

Belfast, Oct. 28 – Major Gen Biddle, writing to the Secretary of the Belfast Chamber of Trade, has expressed deep appreciation for the many kindly acts shown by Belfast citizens to American survivors of the Otranto. The letter says:

“Reports reaching us of the splendid funeral honors accorded to our dead soldiers in Belfast indicate that your authorities and citizens have been more than kind. Thanks also are due to those Belfst ladies and others who sent floral tributes and in other ways showed such a generous and sympathetic spirit.”

Related Posts:

- Otranto Doctor Writes of Ship’s Final Hours

- Otranto Survivor Describes Disaster

- William C. Zeigler

- Berrien County Paid Terrible Toll on the Otranto

- Seeking Descendants of HMS Otranto Disaster Victims and Survivors

- HMS Otranto Sank Ninety-four Years Ago

- OTRANTO SUNK IN COLLISION

- Oct 12, 1918 ~ 372 U.S. Soldiers Lost in Sinking of Otranto

- October 13-15, 1918 ~ RECOVERING CORPSES FROM OTRANTO WRECK

- The American Red Cross and the Otranto Rescue

- J.M. DeLoach Jumped from the HMS OTRANTO

- Ralph Knight ~ Otranto Disaster

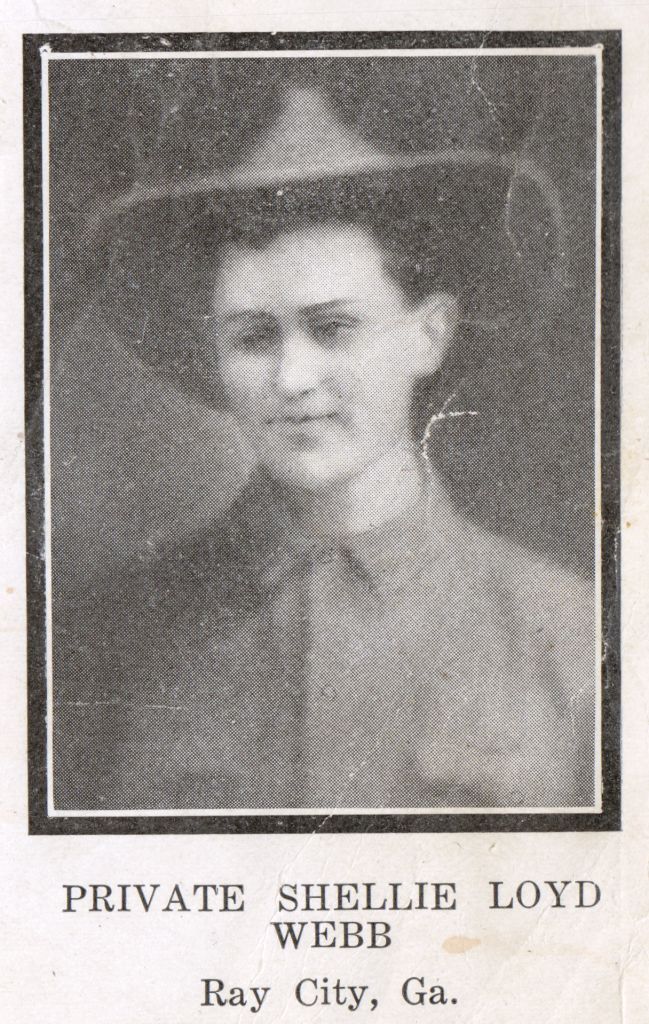

- Shellie Loyd Webb – Lost at Sea

- The Long Trip Home

- Ralph Knight ~ Ray City Soldier ~ WWI

- Thomas Jefferson Sirmons Rests at Mount Pleasant Church Cemetery

- Alvin Claude Bozeman and the Sinking of the HMS Otranto

- Burial of the Otranto Victims

- Bivouac of the Dead

- Red Cross was at the Ready for HMS Otranto Survivors

- The American Red Cross and the Otranto Rescue

- Islay Remembered Otranto Soldiers at Christmas Time

- Let Us Unveil

- Hero of Otranto Rescue Shot Dead

- Armistice Day Memorial to Soldiers from Berrien County, GA Killed During WWI

- Ray City, GA Veterans of World War I

- On the Home Front, Ray City, GA, 1918