Lott Warren became a judge on the Southern Circuit of Georgia and presided at the Lowndes County Grand Jury of 1833.

The people of the Native American village of Aumuculle had a long history of friendship with the American government and white settlers in Georgia. Yet, on the morning of April 23, 1818, soldiers of the Georgia militia under the command of Captain Obed Wright massacred the village. In the attack, a young lieutenant named Lott Warren followed orders to loot and burn the Indian houses, some with people still in them.

- The Chehaw Massacre and Lott Warren

- The Chehaw Expedition

- Attack On Aumuculle (Chehaw)

- Lott Warren and the Arrest of Obed Wright

Attack on Aumuculle (Chehaw).

Obed Wright’s expedition had been formed as a punitive strike against the hostile Creek Indian villages of Philema and Hopaunee, for raiding and plundering white settlements along the Ocmulgee River. Wright’s expedition arrived at Fort Early on the Flint River on April 22, 1818. Despite the specific orders from Governor Rabun, Wright planned to bypass the villages of Philema and Hopaunee and advance his force on Au-muc-cu-lee (Chehaw) where he believed hostile Indians were in residence. Wright ordered the commanding officer of Fort Early, Captain Ebenezer Bothwell, to provide an additional company to support the attack. Although Bothwell disapproved of the plan and insisted that the Aumuculle Indians were friendly, he provided the men Wright required.

“A pilot employed by Capt. Wright took him to the Chehaw town,” according to a later statement made by Lott Warren before the U.S. Congress. Captain Jacob Robinson alleged that upon approaching “within a half mile of the town, we found an Indian herding cattle, the most of which appeared to be white people’s marks and brands. A Mr. McDuffee, of Telfair attached to my corps, swore to one cow as the property of his father, and taken from near where the late depredation on the frontier of Telfair was committed.“

Now absolutely convinced that hostiles were holed up at Chehaw, the expedition advanced on the town. Captain Obed Wright ordered the attack on the Native American village just before noon on April 23, 1818. Captain Dean, a veteran of the War of 1812, ordered a charge, but it was countermanded by Capt. Wright. Captain Robinson led the attack on the right. Half of the village’s warriors were absent, having volunteered to serve with General Jackson in Florida. The town was soon decimated.

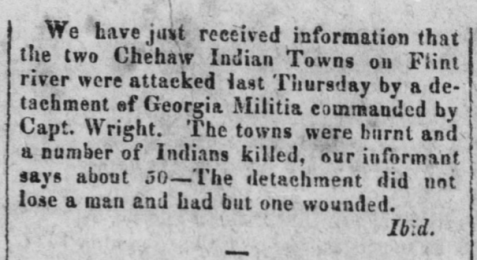

The outcome of the attack was reported by Captain Wright in a letter to Governor Rabun dated April 25, 1818, which was published in the Georgia Journal on May 5, 1818.

The Georgia Journal

May 5, 1818Hartford, (Ga.) April 25, 1818.

His Excellency Governor Rabun;

Sir – I have the honor to inform you that agreeable to your orders, I took up the line of march from this place on the 21st instant, with Captains [Jacob] Robinson’s & [Timothy L.] Rogers’s companies of mounted gun-men, Captains [Elijah] Dean’s and [Daniel] Child’s infantry, together with two detachments under Lieutenants Cooper and Jones, Captain Thomason acting as Adjutant, in all about 270 effective men.

On the night of the 22d I crossed Flint river, and at day break, advanced with caution against the Chehaw Town. The advance guard, when within half a mile of the town, took an Indian prisoner, who was attending a drove of Cattle, and on examination, found some of them to be the property of a Mr. M’Duffy (who was present) of Telfair County.

The town was attacked, between 11 and 12 o’clock, with positive orders not to injure the women, or children, and in the course of two hours, the whole was in flames; they made some little resistance, but to no purpose.

From the most accurate accounts, 24 warriors were killed, and owing to the doors of some of the houses being inaccessible to our men, and numbers of guns being fired at us through the crevices, they were set on fire; in consequence of which, numbers were burnt to death in the houses; In all probability from 40 to 50 was their total loss; some considerable number of warriors made their escape, by taking to a thick swamp; a very large parcel of powder found in the town, was destroyed. It is supposed their chief is among the slain. The town is laid completely desolate, without the loss of a man. We re-crossed the Flint to Fort Early the same evening, making a complete march of 31 miles (exclusive of destroying the town) in 24 hours.

The conduct of the officers and soldiers on this occasion, (as well as on all others) was highly characteristic, of the patriotism and bravery of the Georgians in general.I am sir, with respect, your most

ob’t humble serv’t,

OBED WRIGHT Capt.

(Ga.) Dft. militia Comd’g

Four days after Wright’s attack, Brigadier General Thomas Glascock came upon the scene of destruction. He had returned to Chehaw village on his way to Hartford, his drafted Georgia militia men having completed their term of enlistment in Florida. In early 1818, Glascock had spent considerable time near Chehaw supervising the construction of Fort Early. He had depended on the friendly village for supplies and for intelligence on the movements of hostile Indians in the area.

Some of the men traveling with General Glascock were warriors from Chehaw who had served with him in the campaign against the Seminoles in Florida. All were shocked at finding the people massacred and the village burned out. Glascock, having arrived with depleted provisions had again hoped to resupply his command at Chehaw, but was forced to march his troops on to Fort Early.

In a letter written a week afterwards, Glascock reported the attack to his superior officer, General Andrew Jackson. Glascock’s account of the Chehaw affair is important not only for its description of how 230 militiamen killed “seven men . . . one woman and two Children” but also for how it shaped Jackson’s response to the massacre.

Fort Early, April 30, 1818.

SIR,

I have the pleasure to inform you, that my command has safely reached this place having suffered some little for the want of meat. The Gods have proved equally propitious to us, on our return as on our advance at Mickasuky. Some of my men were nearly out of corn, and searching about some old houses that had not been consumed, to see if they could make any discovery, in entering one of them, to their great astonishment and surprize, they came across the man who was lost from captain Watkin’s company, on the 2d of April. It appears from his statement, that he was taken with a kind of cramp, and was unable to move and became senseless. — When he recovered, he became completely bewildered, and never could reach the camp; he therefore concluded it was prudent to secrete himself in some swamp, and after wandering about some time came across a parcel of corn, on which he subsisted until we found him: he was very much reduced, and apparently perfectly wild. On that night Gray struck a trail, pursued it about a mile and half, came to a small hut, which fortunately contained 50 or 60 bushels of corn, some potatoes and peas, which enabled us to reach the Flint, opposite Chehaw village; when arriving within thirty miles of the place, I sent on major Robinson, with a detachment of 20 men to procure beef. On his arriving there, the Indians had fled in every direction. The Chehaw town having been consumed about four days before, by a party of men consisting of 230, under a captain Wright, now in command of Hartford. It appears that after he assumed the command of that place, he obtained the certificates of several men on the frontier, that the Chehaw Indians were engaged in a skirmish on the Big Bend [Ocmulgee River – Breakfast Branch]. He immediately sent or went to the governor, and received orders to destroy the towns of Filemme and Oponee. Two companies of cavalry were immediately ordered out and placed under his command, and on the 22d he reached this place. He ordered captain Bothwell, to furnish him with 25 or 30 men to accompany him, having been authorized to do so by the governor. The order was complied with. Captain Bothwell told him, that he could not accompany him, disapproved the plan, and informed captain Wright, that there could be no doubt of the friendship of the Indians in that quarter; and stated, that Oponne had brought in a public horse that had been lost that day. This availed nothing; mock patriotism burned in their breasts; they crossed the river that night, and pushed for the town. When arrived there, an Indian was discovered grazing some cattle, he was made a prisoner. I am informed by sergeant Jones, that the Indian immediately proposed to go with the interpreter, and bring any of the chiefs for the captain to talk with. It was not attended to. An advance was ordered, the cavalry rushed forward and commenced the massacre. — Even after the firing and murder commenced, major Howard, an old chief, who furnished you with corn, came out of his house with a white flag in front of the line. It was not respected An order was given for a general fire, and nearly 400 guns were discharged at him, before one took effect — he fell and was bayonetted — his son was also killed. These are the circumstances relative to the transaction — Seven men were killed, one woman and two children. Since then three of my command, who were left at fort Scott, obtained a furlough, and on their way one of them was shot, in endeavoring to obtain a canoe to cross the Flint. I have sent on an express to the officer commanding fort Scott, apprising him of the affair, and one to adjutant Porter, to put him on his guard. On arriving opposite Chehaw, I sent a runner to get some of them in, and succeeded in doing so. They are at a loss to know the cause of the displeasure of the white people. Wolf has gone to the agent to have it inquired into. We obtained from them a sufficient quantity of beef to last us to Hartford, at which place I am informed there is a plentiful supply of provisions. I have the honor to be very respectfully,

Your friend and obedient servant,

[Signed]

THOMAS GLASSCOCK,

Brig. gen. comg. Ga. militia, U.S.S.

General Glascock gave orders that Major James Alston, paymaster to the Georgia Militia, should not pay the soldiers who marched against Chehaw under the orders of Captain Wright, but to pay only those who had remained behind to garrison the station at Hartford, GA.

♦♦♦

Augusta Herald May 5, 1818. The first sketchy newspaper reports on the Chehaw expedition assumed that Captain Obed Wright had followed orders to attack two hostile Indian villages.

Lott Warren’s Account of the Massacre

Among the soldiers in Captain Wright’s command at the Chehaw Massacre was a young lieutenant Lott Warren, who would later serve as the judge on the Southern Circuit of Georgia. Judge Lott Warren presided over the Lowndes County Grand Jury of 1833, at Franklinville, GA, then the county seat of Lowndes County. The role of Lott Warren in these events is described in Portraits of Eminent Americans,

Arrived within a few miles of the Chehaw town, which was supposed to be Philemi [Now the site of Philema, Lee County, GA?], a council of war was called, and it was determined to send forty of the best mounted men to reconnoitre. They discovered large herds of cattle that had been stolen from the whites on the Ocmulgee, and an Indian minding them. Captain Obed Wright, of the Chatham militia, who had volunteered his services, had positive orders from the Governor to destroy the Hoponee and Philemi towns, which were known to be hostile. Captain Wright then formed the command into a column, and gave express orders that the women and children should not be hurt, and that a white flag should be respected. Within half a mile of the main town a gate was opened by an aged warrior, and the troops passed in. Every thing was quiet. The children swung in their hammocks, and the women were beating meal. The cavalry in front fired several pistols to the left, killing the warrior who opened the gate. Capt. Dean ordered a charge, but Capt. Wright countermanded the order. Two Indians were seen loading their guns. About this time, Howard, a friendly chief, was killed, while holding up a white flag. The men dashed off in pursuit of the Indians, who fled in every direction. Lieut. Warren was ordered, with eighteen men, to burn the cabins. First removing whatever was valuable, two or three cabins only were burnt. The command then returned to Fort Early that night, sold the plunder next day, and divided the spoil. Lieut. Warren refused his portion.

It was the opinion of all concerned at the time, that it was Philemi town which had been destroyed. The chief Howard, and two other Indians who placed themselves in the power of the troops, were murdered in cold blood. But the error had been committed rashly, under excitement, and could not be repaired.

∫∫∫

Lieutenant Lott Warren’s recollection of the plundering and selling of trophies taken during the raid supports a report published in the Augusta Chronicle, May 16, 1818, about three weeks after the attack. The Chronicle reported that Wright’s troops sacked and looted the village, the “spoils, consisting of breech-clouts, flaps, shirts, and blankets, some of which were sold (the products divided among the victors), and the remainder kept as patriotic mementos. The ear ornaments of poor old Howard were worn by a Mr. Thompson, of Elbert, acting adjutant of the expedition, as a trophy of his gallant conduct. This being, we understand, boasted of having killed with his own hand, two Chehaws, one of whom had been previously mortally wounded!”

Calls for Justice

Indian Agent D. B. Mitchell wrote to Governor Rabun, requesting an official inquiry “into the conduct of the officers engaged in the enterprise,” and to present the case for reparations to be paid to the survivors of the attack. A copy of this letter is in the collection of the Newberry Library, Chicago. Transcriptions were subsequently published in the Milledgeville Reflector, May 26, 1818, and the National Register, June 13, 1818.

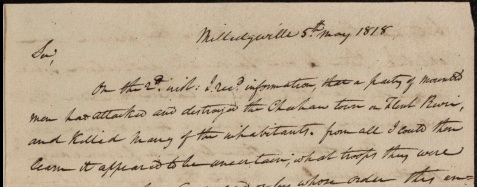

Letter written May 5, 1818 by David Brydie Mitchell, Indian Agent, to William Rabun, Governor of Georgia, protesting the “unwarrantable and barbarous” destruction of Chehaw village.

Indian War. DESTRUCTION OF THE CHEHAW VILLAGE.

Copy of a letter from D. B. Mitchell, esq., agent for Indian affairs, to governor Rabun, dated Milledgeville, May 5, 1818.

Sir,

On the 2d inst I rec’d information that a party of mounted men had attacked and destroyed the Chehaw town on Flint river, and killed many of the inhabitants. From all I could then learn it appeared to be uncertain what troops they were, and under whose command, or by whose order this unwarrantable and barbarous deed had been done; and as the consequences cannot be foreseen which may result, when the justly exasperated warriors of the town return, and find their town and property destroyed;—their unoffending and helpless families killed or driven into the woods to perish, whilst they were fighting their and our enemies, the Seminoles, I deemed it best to come to the state and endeavor to procure correct information. I now find that the party had been sent out by your orders, but failed to execute them; and that the attack on Chehaw was unauthorized. I present the case for the consideration of your Excellency, under a confident hope, that as the people of Chehaw were not only friends, but that their conduct during the present war entitle them to our favor and protection, some immediate step will be taken to render that satisfaction which is due for so great an injury.

The extent of their loss in a pecuniary point of view, I am not at this moment prepared to state, but so soon as I return to the agency I will loose no time in having that ascertained; and in the mean time, permit me to suggest the propriety of instituting some legal inquiry into the conduct of the officers engaged in the enterprise. I leave this early in the morning for the agency, from whence I will address you again upon this subject.

I have the honor to enclose an extract of a letter rec’d from old Mr. Barnard on this subject, the contents of which is corroborated by a verbal statement of the Wolf Warrior, who came to me directly from the spot.

I am, sir,

with high consideration and respect

Your Very Ob Servt,

D. B. MITCHELL, agent for I. A.

P. S.—Since writing the above, I have rec’d a letter from the Little Prince, [speaker of the Lower Creeks,] upon this subject, a copy of which l also enclose.

![The Chief on the left hand in this Etching, was the well-known Little Prince was head of the Creek Nation of Indians, and a man of considerable energy of purpose and respectability of character...The position of his hands, with fingertips touched to thumbs, was described as being characteristic of the old man. [On the right] - One of those settlers who, in other parts of the country, are called squatters, but who bear the appellation of Crackers in Georgia, - men who set themselves down on any piece of vacant land that suits their fancy, till warned off by the legal proprietor. The man here sketched lived...almost entirely by hunting and shooting. Drawn with the Camera Lucida by Capt B. Hall, R.N.](https://raycityhistory.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/little-prince-speaker-the-lower-creeks.jpg?w=477)

The Chief on the left in this etching was the well-known Little Prince, head of the Creek Nation of Indians, and a man of considerable energy of purpose and respectability of character…The position of his fingers, was described as being characteristic of the old man. [On the right] – One of those settlers who, in other parts of the country, are called squatters, but who bear the appellation of Crackers in Georgia, – men who set themselves down on any piece of vacant land that suits their fancy, till warned off by the legal proprietor. The man here sketched lived…almost entirely by hunting and shooting. Drawn with the Camera Lucida by Capt B. Hall, R.N.

Copy of a letter from the Little Prince, speaker of the Lower Creeks, to D.B. Mitchell, Indian Agent to the Creeks, dated Fort Mitchell, April 25, 1818.

Fort Mitchell, April 25, 1818

“My Great Friend: I have got now a talk to send to you. One of our friendly towns, by the name of Chehaw, has been destroyed. The white people came and killed one of the head men, and five men and a woman, and burnt all their houses. All our young men have gone to war with General Jackson, and there is only a few left to guard the town, and they have come and served us this way. As you are our friend and father, I hope you will try and find out, and get us satisfaction for it. You may depend upon it that all our young men have gone to war but a few that are left to guard the town. Men do not get up and do this mischief without there is some one at the head of it, and we want you to try and find them out.”

(signed) TUSTUNNUGGIE HOPOIE

∫∫∫

Copy of a letter from Timothy Barnard, esquire (a white man), residing on Flint River, to D. B. Mitchell, agent for I. A.

April 30, 1818.

Sir,

The Wolf Warrior, the bearer of this, has just arrived here, and brings bad news from the Au,muc,culla town (Chewhaw.) Nearly all the warriors belonging to that town are now with our army. Seven days past a company of white people collected and rushed on the town; and as there were but few red people there, and all friendly, just what few were left to guard their town, the rest still with our army, the white people killed every one they could lay their hands on: killed the old chief Tiger King, and one other chief, both I have known always to be friendly to our color, ever since I have been in this land. The whole of what are killed is nine men and one poor old woman. They took of what horses were there, the owners of some of which are still living; they took the horses to the fort, which is not far from the town they have destroyed. The chiefs that are still alive, beg that you will get their horses, or any thing else returned. The red people don’t know whether it is the regular troops, or Georgia militia that have committed this unwarrantable act. I have wrote you all that I think necessary – If you see cause to write anything to me, to inform them of, I will do it with pleasure. If these people do not get some friendly treatment for the damage done them, I am afraid, when their warriors return back from our army, something bad will happen to some of our color. I am very sorry to have to write you on such a horrid piece of business. I write you in haste, as the bearer is in great hurry to see you.

I remain, sir, your friend, and most ob’t serv’t

(Signed) T. BARNARD

Timothy Barnard wrote with some authority: He was the “first white settler known to live on land now in Macon County, operated an Indian Trading Post on the west bank of the Flint River, from pre-Revolutionary days until he died in 1820. For his loyalty to the American cause, his sons by his Uchee wife were given reserves in the County. Trusted by his Indian neighbors, he became Assistant and Interpreter to Benjamin Hawkins, Indian Agent… He blazed Barnard’s Paths, principal early trails from the Chattahoochee River to St. Mary’s and St. Augustine. = Waymarking.com

♦

Every one will admit that the anger which blazed up in the heart of General Jackson when he received this intelligence was most natural and most righteous. He instantly dispatched a party to arrest Captain Wright, and convey him in irons to Fort Hawkins. The following letters, all dated on the same day, are of the kind that require no explanation:—

GENERAL JACKSON TO MAJOR DAVIS.

“HEADQUARTERS Division of the South,

“May 7th, 1818.}“SIR: You will send, or deliver personally, as you may deem most advisable, the inclosed talk to Kanard, with instructions to explain the substance to the Chehaw warriors.

“You will proceed thence to Hartford, in Georgia, and use your endeavors to arrest and deliver over, in irons, to the military authority at Fort Hawkins, Captain Wright, of the Georgia militia, who has been guilty of the outrage against the woman and superannuated men of the Chehaw village. Should Wright have left Hartford, you will call upon the Governor of Georgia to aid you in his arrest. To enable you to execute the above, you are authorized to take a company with you of the Tennesseans that went from hence lately for Fort Scott, and await, if you think it necessary, the arrival of the Georgians, now on march, under Major Porter. “You will direct the officer commanding at Fort Hawkins to keep Captain Wright in close confinement, until the will of the President be known. “The accompanying letters, for the Secretary of War and Governor of Georgia, you will take charge of until you reach a post-office. “ANDREW JACKSON.”

∫∫∫

Major General A. Jackson.

Gen. Jackson to the Chiefs and Warriors of Chehaw Village.

On my march to the west of Apalachicola, May 7, 1818.Friends and Brothers,

I have this morning received, by express, the intelligence of the unwarrantable attack of a party of Georgians on the Chehaw village, burning it, and killing six men and one woman.Friends and Brothers,

The above news fills my heart with regret and my eyes with tears. When I passed through your village your treated me with friendship, and furnished my army with all the supplies you could spare; and your old chiefs sent their young warriors with me to fight, and put down our common enemy. I promised you protection: I promised you the protection and fostering friendship of the United States by the hand of friendship.Friends and Brothers,

I did not suppose there was any American so base as not to respect a flag; but I find I am mistaken. I find that Captain Wright of Georgia has done it. I cannot bring your old men and women to life, but I have written to your father, [James Monroe] the President of the United States, the whole circumstance of your case, and I have ordered Captain Wright to be arrested and put in irons, until your father, the President of the United States, makes known his will on this distressing subject.

Friends and Brothers,

Return to your village; there you shall be protected, and Capt. Wright will be tried and punished for this daring outrage of the treaty, and murder of your people; and you shall also be paid for your houses, and other property that has been destroyed; but you must not attempt to take satisfaction yourselves; this is contrary to the treaty, and you may rely on my friendship, and that of your father, the president of the United States.I send you this by my friend, Major [John M.] Davis, who is accompanied by a few of my people, and who is charged with the arrest and confinement of Captain Wright; treat them friendly; they are your friends; you must not permit your people to kill any of the whites; they will bring down on you destruction. Justice shall be done to you; you must remain in peace and friendship with the United States. The excuse that Captain Wright has made for this attack on your village, is that some of your people were concerned in some murders on the frontiers of Georgia; this will not excuse him. I have ordered Captain Wright, and all the officers concerned in this transaction, in confinement, if found at Hartford. If you send some of your people with Major Davis, you will see them in irons. Let me hear from you at Fort Montgomery. I am your friend and brother.

ANDREW JACKSON

Maj. Gen. Com’dg, Division of the South∫∫∫

GEN. JACKSON TO WILLIAM RABUN, GOVERNOR of GEORGIA.

“Seven miles advance of Fort Gadsden, May 7th, 1818.

“SIR:

I have this moment received by express the letter of General Glascock (a copy of which is inclosed) detailing the base, cowardly and inhuman attack on the old women and men of the Chehaw village, while the warriors of that village were with me fighting the battles of our country against the common enemy, and at a time, too, when undoubted testimony had been obtained and was in my possession, and also in the possession of General Glascock, of their innocence of the charge of killing Leigh and the other Georgian at Cedar Creek.

“That a Governor of a State should assume the right to make war against an Indian tribe, in perfect peace with and under the protection of the United States, is assuming a responsibility that I trust you will be able to excuse to the government of the United States, to which you will have to answer, and through which I had so recently passed, promising the aged that remained at home my protection, and taking the warriors with me in the campaign, is as unaccountable as it is strange. But it is still more strange that there could exist within the United States a cowardly monster in human shape that could violate the sanctity of a flag when borne by any person, but more particularly when in the hands of a superannuated Indian chief, worn down with age. Such base cowardice and murderous conduct as this transaction affords has not its parallel in history, and shall meet with its merited punishment.

“You, sir, as Governor of a State within my military division have no right to give a military order whilst I am in the field; and this being an open and violent infringement of the treaty with the Creek Indians, Captain Wright must be prosecuted and punished for this outrageous murder, and I have ordered him to be arrested and to be confined in irons until the pleasure of the President of the United States is known upon the subject. If he has left Hartford before my order reaches him, I call upon you as Governor of Georgia to aid in carrying into effect my order for his arrest and confinement, which I trust will be afforded, and Captain Wright brought to condign punishment for this unparalleled murder. It is strange that this hero had not followed the trail of the murderers of your citizens; it would have led to Mickasucky, where we found the bleeding scalps of your citizens; but there might have been more danger in this than attacking a village containing a few superannuated women without arms or protectors. This act will to the last age fix a stain upon the character of Georgia.

“I have the honor, etc.,

“ANDREW JACKSON.”

∫∫∫

There were those who came to Captain Wright’s defense. Jacob Robinson, captain of the Laurens County Light Dragoons, who participated in the attack, gave an account that significantly differed from that of Lieutenant Lott Warren. Robinson wrote in the May 5, 1818 edition of the Milledgeville Georgia Journal:

I find some people are misled, or under wrong impressions, as to the late expedition to the Nation, supposing the town destroyed by Capt. Wright’s detachment (acting under the orders of the Executive) was actually friendly. As an officer commanding a volunteer corps on that occasion, I feel it my duty to state, that when the army, or rather the advance, appeared within half a mile from the town, we found an Indian herding Cattle, the most of which appeared to be white people’s marks and brands. A Mr. M’Duffee of Telfair, attached to my corps, attached to my corps, swore to one cow as the property of his father and taken from near where the late depredation on the frontier of Telfair was committed. We found in the town a rifle gun, known to be the one taken from a man of the name of Burch, who fell in the before mentioned skirmish [Battle of Breakfast Branch]. When we determined to attack the town, positive orders were given to spare the women and children, and all such as claimed protection; which was strictly enforced by the Officers, so far as was practicable, or came within my observation. My Troop was directed to advance on the right of the Town, which was done speedily. On our approach & before a man of my company fired a gun, the Indians, from a sink or cave near the path we were in, fired apparently 12 or 15 guns at my men; the bullets were distinctly heard by all, and slightly felt by two or three of the men. Some of the Indians found in the town were painted; all I saw evinced a disposition to fight or escape. We killed 24 warriors and burnt the town, agreeable to orders. A considerable number of new British muskets, carbines, &c. were destroyed – in nearly all of the houses there were explosions of gun-powder. The Indian we found herding cattle informed us that Hoponee resided there, and was then in the town. I am not certain whether he was slain or not. In possession of the last Indian killed, who was painted red, was found letters, one from Col. Milton, the other from Maj. Minton, both addressed to Gen’l Gaines, the seals of which had been broken.

JACOB ROBINSON

April 30th, 1818

Captain Jacob Robinson was later court martialed and cashiered for making out a false payroll report for the service of his men who participated in the Chehaw Massacre, keeping the excess pay for himself (Georgia Journal, Sept 28, 1819). Those serving on the military court that convicted Robinson included Captain Elijah Dean and Lieutenant Charles S. Guyton, who served with Robinson at the attack on Chehaw. Robinson later attempted to coerce them and other members of the court, under threat of lawsuit, to certify that his men had been paid properly.

On May 20, 1818, Governor Rabun responded to Mitchell, U.S. agent to the Creek Indians regarding letters that he has received about Captain Obed Wright’s unwarranted attack on innocent Creeks in the Chehaw Village. Rabun tries to justify the attack by explaining that Captain Wright’s detachment descended on the village because they had been told by credible sources that the Indians living there were under the leadership of Chief Hopaunee, whose warriors had been hostile towards frontier settlers. Rabun apologizes for the mistake but says that civilian casualties are an unfortunate part of war. He laments the negative attention that this attack has generated among the people of the state, particularly as it obscures the recent “outrages” committed by the Creeks. To appease the public, Rabun has ordered a tribunal to investigate the attack. In the meantime, he urges Mitchell to express his apologies to the Creeks.

Executive Department Georgia Milledgeville 20th May, 1818.

SirI have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of yours of the 6th inst. [instant] enclosing a Copy of a letter from Old Mr. Barnard, & one from the Little Prince, Speaker of the Lower Creeks, both on the subject of the late unfortunate attack made by a detachment of Georgia Militia under Captain Wright on the Chehaw Village which had previously been supposed to be friendly.

I have examined these Communications with the candor their importance naturally required. It is unquestionably your duty as Agent to attend to the complaints of the Red people and cause justice to be done to them as far as your powers will extend. — It will also readily be acknowledged by all, that my duty as Governor of the State, requires that I should defend the cause of the Whites as far as that cause can be supported by the great principles of Justice. — As you have furnished me with the Indian account of this transaction, and assured me of the friendship towards the whites that existed among them prior to the attack; I feel it incumbent on me to explain to you and thro’ you to the Nation over which you preside, the motives by which the Officers were actuated who conducted the enterprise and the grounds upon which they will attempt to justify the proceeding, or extenuate the guilt that may in the view of some men be attached to them — You will readily acknowledge the decided and inveterate hostility of those Indians which belong to the Vilages under the immediate direction and controul of the Chiefs Hopaunee and Phelemmee, and that the orders which eminated from this department for their chastisement was both necessary and proper — You are also well apprised that the orders given confined them Specially to that object — So far then as respects myself I feel perfectly justified in the measures I adopted and which I deemed essentially necessary to prevent a repetition of the horrid murders and depredations committed by those Indians on our unprotected frontier —

I will now undertake to offer in behalf of the detachment the best apology for their conduct that I may be able to furnish and which I am authorized to state, can be supported by ample proof. — When the detachment was on their way to and reached the neighborhood of Fort Early they were credibly informed by several persons of veracity that the celebrated old Chief Hopaunee (whose town had all joined the hostile party) had removed and was at that time living in [added: the] Village upon which the attack was made, and was considered as their principal leader, and that a great portion of them was alledged to be under his immediate direction, altho’ part of them might be with [Chief William] McIntosh — They therefore considered themselves authorized to attack it as being one of Hopaunee’s Towns. — The result I need not mention, as you have seen the statements made by Captains Wright and Robinson which I am authorized by very respectable testimony to assure you, was substantially true, except as to the number reported to have been killed, which was fortunately incorrect. —

Now Sir if I have been misinformed and given a wrong construction to this affair, I should like very much to have more Correct information, but if it should be founded in fact, what more can you or the Indians require, than for me to assure you, that I regret the circumstance, and consider it as one of the misfortunes attendant on war, where the innocent frequently suffer in Common with the guilty — I have however, for the satisfaction and information of the public, as well as for the reputation of the Officer who commanded the expedition, Ordered him to this place for the purpose of having his conduct investigated by a military tribunal. — This unfortunate affair has been shamefully misrepresented by many of our Citizens, whose delicate feelings seem to have forgotten the many wanton outrages that have been committed on our frontier by the Indians, and would even cover the whole State with disgrace, merely because this small detachment have in this instance carried their resentment to an improper extent. —

The experience of all ages have shewn, that it it is much easier for us to complain of the conduct of others (and especially those in responsible Stations) than to correct our own. —

I have ascertained, that the property left by the Indians who were run off from, or near Docr. Birds Store on the Ocmulgee, some time past, is now in the possession of Mr. Richard Smith in the lower end of Twiggs County, and will be delivered at any time when proper application shall be made. —

You will please to assure the Red people under your care, that I feel a disposition to maintain peace and friendship with them on liberal terms. —

I have the honor to be,

Very Respectfully your Ob. [Obedient] Servant.

[Signed] Wm [William] Rabun

A heated exchange of letters ensued between General Jackson and Governor Rabun regarding the jurisdiction of military authority in Georgia. The full text of the correspondence of Governor William Rabun and General Andrew Jackson is available in the Life of Andrew Jackson: In Three Volumes. II The incident came under intense national scrutiny and was eventually reviewed by Congress.

The whole issue became an early States’ Rights argument. Jackson maintained that a Governor had no right to issue orders to the militia while a Federal officer was in the field, and in a series of heated letters with Rabun, called Telfair county residents ” . . . a few frontiers settlers . . . who had not understanding enough to penetrate the designs of my operations.” Rabun fired back that Jackson’s own actions at St. Augustine were on par with Wright’s at Chehaw, and that Jackson was more interested in his career than in protecting Georgians. – Kevin J. Cheek

General Jackson viewed the incident as shamefully disloyal and extremely dangerous, with the potential to turn the friendly Chehaws, who Glascock described as “at a loss to know the cause of this displeasure of the white People,” into enemies. Soon after he received Glascock’s account of the massacre, Jackson wrote to William Rabun, the governor of Georgia, calling Wright a “cowardly monster in human shape” and demanding that “Capt. Wright must be prosecuted and punished for this outrageous murder.” – Massacre of American Indian Allies, 1818

Related Posts:

- The Chehaw Massacre and Lott Warren

- The Chehaw Expedition

- Judge Lott Warren

- Isham Jordan Fought Indians, Opened Early Wiregrass Roads