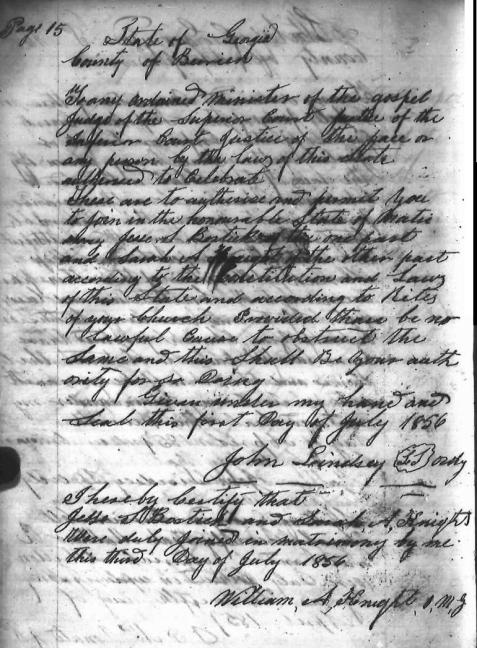

Green Bullard was a pioneer settler of Berrien county. He came to the area of present day Ray City, GA with his parents some time before 1850. They settled on 490 acres of land acquired by his father, Amos Bullard, in the 10th Land District, then in Lowndes county, GA (cut into Berrien County in 1856).

Following the commencement of the Civil War Green Bullard, and his nephew, Alfred Anderson, went to Nashville, GA and signed up on March 4, 1862 with the Berrien Light Infantry, which was being formed at that time. The company traveled to Camp Davis, a temporary training camp that had been established two miles north of present day Guyton, GA (then known as Whitesville, GA). There they received medical examinations and were mustered in as Company I, 50th Georgia Regiment on March 30, 1862.

For many of the men in the 50th Regiment, this was the farthest they had ever been from home and the largest congregation of people they had ever seen. Coming from the relative isolation of their rural farms and small south Georgia communities, many received their first exposure to communicable diseases such as Dysentery, Chicken Pox, Mumps, Measles, or Typhoid fever. The first cases of Measles were reported within days of the men’s arrival and at times nearly two-thirds of the regiment were unfit for duty due to illness. On April 7, 1862 Bullard’s nephew, Alfred Anderson, reported sick with “Brain Fever” [probably either encephalitis or meningitis] while at Camp Davis, with no further records of his service. With so many down sick, the Regiment could barely drill or even put on guard duty. As the summer wore on, those that were fit participated in the barricading of the Savannah River and in coastal defenses.

“In May 1862 the Confederate Government established a General Hospital in Guyton, GA,” near Camp Davis. “This hospital was located on a nine acre tract of land adjacent to the Central Railroad… From May 1862 to December 1864, this hospital provided medical care, food, clothing, and lodging for thousands of sick and wounded Confederate soldiers.” – Historical Marker, Guyton Confederate General Hospital.

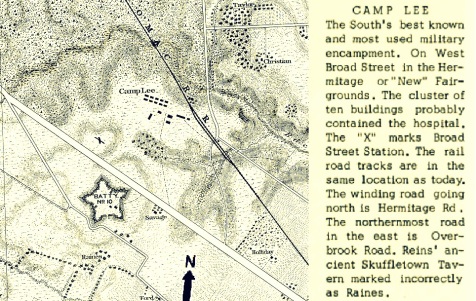

Finally, in mid-July the 50th Regiment moved out via train to Richmond, VA where they joined Drayton’s Brigade in the CSA Army of Northern Virginia. The Regiment bivouacked first at Camp Lee. Camp Lee was a Confederate training camp that had been converted from the Hermitage Fair Grounds near Richmond, with the exhibit halls converted into barracks and hospitals. The grounds were filled with the tents of infantry and artillery companies. The men bathed in a shallow creek, “but it is doubtful if their ablutions in that stream are productive of cleanliness,” opined the Richmond Whig in August of 1862.

Camp Lee, near Richmond, VA. Text from Confederate Military Hospitals in Richmond, by Robert W. Waitt, Jr., 1964.

On August 20, 1863 the 50th Georgia Regiment moved out to see their first real action. but by that time company muster rolls show that Green Bullard was absent from the unit, with the note “Left at Lee’s Camp, Va. sick Aug 21st.” On September 7, 1862 Bullard was admitted to the Confederate hospital at Huguenot Springs, VA. Company mate Pvt William W. Fulford was also attached to the convalescent hospital at that time. The hospital muster roll of October 31, 1862 marks him “present: Bounty Paid”. He remained “absent, sick” from Company I at least through February, 1863.

In 1862, the Huguenot Springs Hotel was converted to a Confederate hospital. On September 7, 1862 Private Green Bullard, Company I, 50th Georgia Infantry, was one of the patients convalescing at the hospital.

On June 19, 1863 Bullard was admitted to Chimborazo Hospital Division No. 2, Richmond, VA this time with typhoid pneumonia. Typhoid fever was a major killer during the war. At that same time, James A. Fogle was a Steward at Chimborazo Division No. 3. Fogle was later promoted to Assistant Surgeon, and after the war came to Berrien County to open a medical practice at Alapaha, GA.

Chimborazo Hospital, the “hospital on the hill.” Considered the “one of the largest, best-organized, and most sophisticated hospitals in the Confederacy.”

Library of Congress

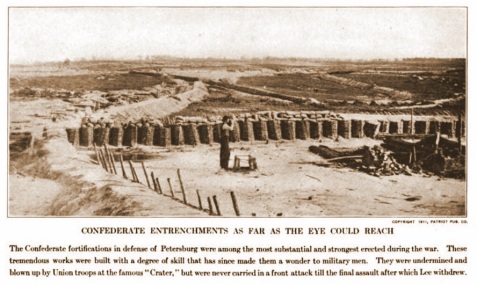

Sometime before February of 1864 Green Bullard returned to his unit. Records show he drew pay on February 29, 1864 and again on August 31 of that year. By October, 1864 he was again sick, but remained with his company. He continued fighting through his illness through November and December,1864. It was during this period (1864) that the 50th Georgia Regiment was engaged in battles at The Wilderness (May 5–6, 1864), Spotsylvania Court House (May 8–21, 1864), North Anna (May 23–26, 1864), Cold Harbor (June 1–3, 1864, Petersburg Siege (June 1864-April 1865, and Cedar Creek (October 19, 1864.)

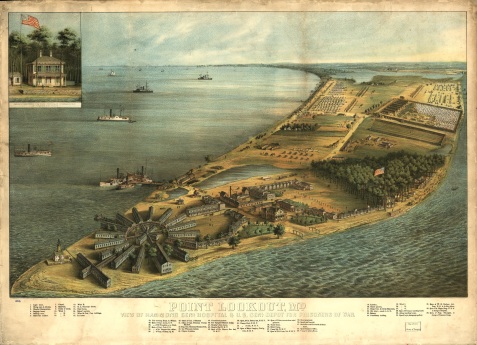

At Cedar Creek, it is estimated that the Georgia 50th Regiment suffered more than 50% casualties. Among those captured was Jesse Bostick of Company G, the Clinch Volunteers. Bostick was sent to Point Lookout, Maryland, one of the largest Union POW camps. (see Jesse Bostick and the Battle of Cedar Creek.)

Receiving and Wayside Hospital, Richmond, VA. was an old tobacco warehouse converted to a receiving hospital because of its nearness to Virginia Central Railroad depot.

By January, 1865 Bullard was too weak to continue fighting. He was sent to Receiving and Wayside Hospital (General Hospital No. 9), Richmond, VA. From there he was transferred to Jackson Hospital, Richmond, VA where he was admitted with dysentery, which was perhaps the leading cause of death during the Civil War. Two months later, March 14, 1865 Bullard was furloughed from Jackson Hospital. No further service records were found. Following less than one month, on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, VA ending the War.

Twice as many Civil War soldiers died from disease as from battle wounds, the result in considerable measure of poor sanitation in an era that created mass armies that did not yet understand the transmission of infectious diseases like typhoid, typhus, and dysentery… Confederate men died at a rate three times that of their Yankee counterparts; one in five white southern men of military age did not survive the Civil War. http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/travel/national_cemeteries/death.html

Despite the odds and repeated bouts of serious illness, Green Bullard survived the war and returned to home and farm in Berrien County, GA.

Related Posts:

![Prisoners at Point Lookout, MD taking the oath of allegiance. A group of prisoners stand in a building, with the U.S. Flag draped across the ceiling, each with his hand on a Bible. A Union officer stands at a dias administering the oath of allegiance to the Union. Image courtesy of Civil War Treasures from the New-York Historical Society, [Digital ID, nhnycw/ae ae00007] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ndlpcoop/nhihtml/cwnyhshome.html](https://raycityhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/oath-at-pt-lookout.jpg?w=477&h=345)