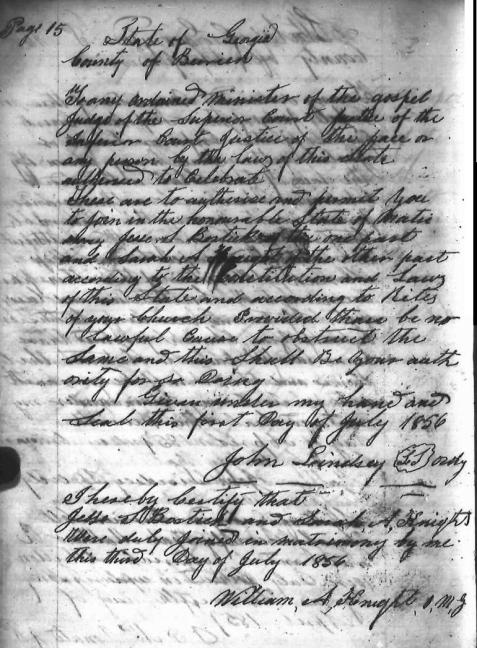

In the 1850s Jesse and Sarah Bostick made their home in Berrien County in the vicinity of present day Ray City, GA. Jesse Bostick, born 1836 in Duplin County, NC was the eldest son of Treasy Boyette and John Bostick. His wife, Sarah Ann Knight, was a daughter of Nancy Sloan and Aaron Knight of Berrien County, GA.

On March 22, 1862, Jesse S. Bostick enlisted in the Clinch Volunteers, which mustered in as Company G, Georgia 50th Infantry Regiment. This unit was quickly dispatched to Virginia where they engaged in battle. Through 1862 and 1863 they fought battles all over Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia and Pennsylvania. The 50th GA Regiment’s bloodiest day was September 14, 1862 at the Battle of South Mountain, where the 50th GA Regiment suffered a casualty rate of 86% – 194 killed or wounded out of an effective force of about 225 men (see William Guthrie and the Bloody Battle of South Mountain).

While Jesse was away fighting in the war, tragedy struck at home. In 1863, his wife and youngest daughter died.

Jesse continued to fight with his unit in engagements at Gettysburg, PA and Knoxville, TN among others. About 15 Feb 1864, shortly after the battle at Cumberland Gap, TN, he was promoted to Full 3rd Sergeant.

In the late summer and early fall of 1864, the 50th Georgia Regiment was fighting all up and down the Shenandoah Valley. The 50th Georgia Regiment was a part of General Kershaw’s Division, in General Early’s Army of the Valley. The Union forces under the command of General Philip Sheridan were engaged in destroying the economic base of the Valley, including crops in the field and stored goods, attempting to deprive General Robert E. Lee’s army of needed supplies.

In mid-October Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah was encamped at Cedar Creek, Virginia while the 50th Georgia Regiment and the rest of General Early’s Confederate forces had withdrawn to defensive positions at Fisher’s Hill, about three miles distant. Believing the Confederate units in Shenandoah Valley too weak to attack his numerically superior force, on October 15 Sheridan returned to Washington D.C. to meet with General Grant and Secretary of War Staunton to begin planning the next phase of the war. By October 18, Sheridan was returning to the scene and while in route spent the evening of the 18th at nearby Winchester, VA.

Seizing on the over confidence of the Union forces, Confederate General Early decided to launch a surprise attack across Cedar Creek in the early morning hours of October 19, 1864. The men of the 50th Georgia regiment spent the day before the attack in preparations, cooking provisions and stocking their ammunition.

Early deployed his men in three columns in a night march, lit only by the moon. The men moved out at midnight, with all gear secured against chance noise they marched in silence. By 5:00 am Kershaw’s Division crossed Cedar Creek at Bowmans Mill Ford, with the 50th Georgia Regiment in the lead.

Just before sunrise, operating under a cover of dense fog, the confederate forces struck. The surprise was complete, and the Union position was quickly overrun. The Confederates took hundreds of Union prisoners, many still in their bedclothes, and captured eighteen guns.

Sheridan was away at Winchester, Virginia, at the time the battle started. Hearing the distant sounds of artillery, he rode aggressively to his command. (Thomas Buchanan Read wrote a famous poem, Sheridan’s Ride, to commemorate this event.) He reached the battlefield about 10:30 a.m. and began to rally his men. Fortunately for Sheridan, Early’s men were too occupied to take notice; they were hungry and exhausted and fell out of their ranks to pillage the Union camps.

Sheridan’s Ride, October 19, 1864.

By 4 p.m., Sheridan had rallied and reorganized his troops to mount a counterattack. The Union divisions were now reinforced by Brig. Gen. George A. Custer‘s cavalry division, which broke the Confederate lines. Custer’s cavalry chased the disorganized Confederates all the way back to Fisher’s Hill. The destruction a bridge in the Confederate rear cut off their escape route, “blocking up all the artillery, ordnance and medical wagons, and ambulances which had not passed that point.” At Fisher’s Hill, the Confederates managed to regain some composure, organizing a defense and an orderly retreat. Despite the reversal, the Confederates took with them some 1500 Union prisoners that had been captured in the morning’s attack.

Casualties on the Confederate side were estimated as being “about 1,860 killed and wounded, and something over 1,000 prisoners” captured by Union forces. The Union took 43 guns (18 of which were their own guns from the morning), and supplies that the Confederacy could not replace. The battle was a crushing defeat for the Confederacy. They were never again able to threaten Washington, D.C., through the Shenandoah Valley, nor protect the economic base in the Valley. The reelection of Abraham Lincoln was materially aided by this victory and General Phil Sheridan earned lasting fame.

It is estimated that the Georgia 50th Regiment suffered more than 50% casualties in the Battle of Cedar Creek. In Jesse Bostick’s unit, Company G, two men were mortally wounded, two others received wounds and nine were taken prisoner. Quarterman Staten, Captain of Company G, was severely wounded, but was transported to a hospital and eventually furloughed home to Echols County, GA.

Jessie Bostick was among those captured.

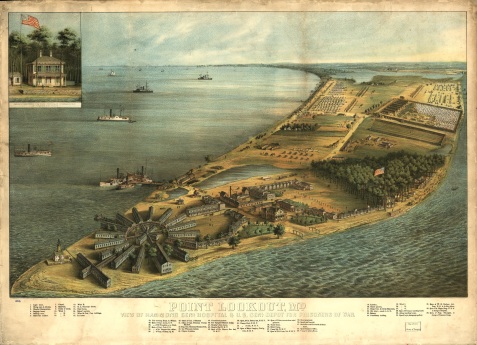

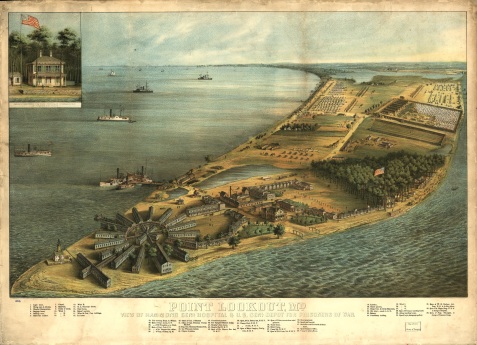

As a prisoner of war he was sent to Point Lookout, Maryland, one of the largest Union POW camps. During the war, a number of captured soldiers from the Ray City area and Berrien County went through the POW depot at Point Lookout, among them John T. Ray, Benjamin Harmon Crum, Benjamin Thomas Cook and Aaron Mattox.

The conditions at Point Lookout were horrific – more than 20,000 men crammed into tents in a prison built to hold 10,000. Nearly 4000 Confederate prisoners died at Point Lookout, about 8 percent of the 50,000 men who passed through the prison camp during the war.

Point Lookout, MD. Hammond General Hospital and U.S. General Depot for Prisoners of War.

Jesse Bostick survived at Point Lookout for four cold months before finally being exchanged on March 21, 1865.

![Prisoners at Point Lookout, MD taking the oath of allegiance. A group of prisoners stand in a building, with the U.S. Flag draped across the ceiling, each with his hand on a Bible. A Union officer stands at a dias administering the oath of allegiance to the Union. Image courtesy of Civil War Treasures from the New-York Historical Society, [Digital ID, nhnycw/ae ae00007] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ndlpcoop/nhihtml/cwnyhshome.html](https://raycityhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/oath-at-pt-lookout.jpg?w=477&h=345)

Prisoners at Point Lookout, MD taking the oath of allegiance. A group of prisoners stand in a building, with the U.S. Flag draped across the ceiling, each with his hand on a Bible. A Union officer stands at a dias administering the oath of allegiance to the Union. Image courtesy of Civil War Treasures from the New-York Historical Society, [Digital ID, nhnycw/ae ae00007] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ndlpcoop/nhihtml/cwnyhshome.html

With the end of the war, Jesse Bostick returned to his home in Berrien County, Ga. Within six months of the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Jesse Bostick married Mrs. Nancy Corbitt Lastinger. She was the widow of James G. Lastinger, another confederate soldier who served with the 29th Georgia Regiment (the Berrien County Minutemen) and died in a Union hospital in 1864.

Jesse and Nancy Bostick lived out their days in Berrien County, GA. They were buried across the Alapaha River in present day Atkinson County at Live Oak Cemetery, where others of the Corbitt family connection are buried.

![Prisoners at Point Lookout, MD taking the oath of allegiance. A group of prisoners stand in a building, with the U.S. Flag draped across the ceiling, each with his hand on a Bible. A Union officer stands at a dias administering the oath of allegiance to the Union. Image courtesy of Civil War Treasures from the New-York Historical Society, [Digital ID, nhnycw/ae ae00007] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ndlpcoop/nhihtml/cwnyhshome.html](https://raycityhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/oath-at-pt-lookout.jpg?w=477&h=345)